Global Financial Safety Net: Regional Reserve Pools and Currency Swap Networks of Central Banks

You can read this post from two perspectives

- Geo Strategic (International Financial and Economic Architecture)

- Financial and Economic stability / Macro-prudential Policy

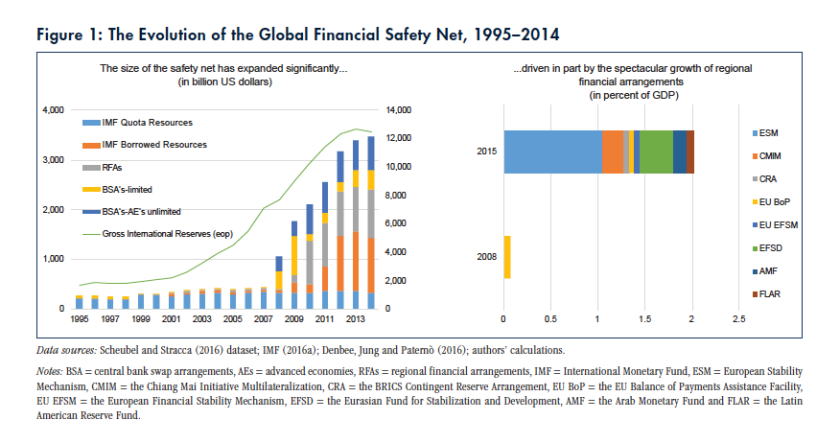

Recent Financial Crisis has exposed the fact that global financial liquidity can be in shortage. Since US Dollar is the global currency and is used in more that 40 percent of all financial transactions globally.

Asian Countries faced dollar shortage during 1997-1998 asian financial crisis. Recent Global Financial crisis caused dollar shortage in advanced countries. US Central Bank Federal Reserve responded by setting up currency swap lines with central banks of other countries. These swap lines were made permanent in 2013.

After Asian financial crisis in 1997, many countries in developing world started accumulating FX reserves. There was also a swap agreement (known as Chiang Mai Initiative) which was set up between ASEAN countries in south east Asia.

Nations also go to IMF to get conditional financing which they do not like to do. New Trend is toward regional pooling of financial resources. Latest example is BRICS CRA.

Even advanced economies such as EU have established European Stability Mechanism (ESM).

Chiang Mai Initiative has been revamped as Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralism (CMIM).

Financial and Economic Stability / Macro Prudential Policy

A. Reserve Pools

- Chiang Mai Initiative (CMI)

- Chiang Mai Initiative Multi-Lateralism (CMIM)

- BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA)

- European Stability Mechanism (ESM)

B. Currency Swap Lines

- Federal Reserve Central Bank US Dollar Swap Lines

- PBOC China Central bank RMB Swap Lines

C. Global

- IMF Financing

D. Self Insurance

- Nation’s Foreign Exchange (FX) Reserves

From The decentralised global monetary system requires an efficient safety net

The global financial safety net as a set of protection mechanisms

The current decentralised system also lacks a central authority that is actively integrated and, above all, contractually bound into the maintenance of the monetary system by providing temporary liquidity, such as the IMF in the Bretton Woods system. Instead, various protection mechanisms have evolved because the current system has not led to greater external stability of national economies and the global economy. The problem of volatile capital flows became particularly clear once again in the course of the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009. For emerging market economies, the warning of a sudden reversal of capital flows has been omnipresent ever since the Asian crisis. However, the last crisis has demonstrated that even for industrialised countries their developed financial markets are a significant contagion mechanism for crisis developments. The following are regarded as key elements of the global financial safety net:11

International reserves. These include official foreign exchange and gold reserves as well as claims on inter-national financial institutions such as the IMF that can be rapidly converted into foreign currency under the countries’ own responsibility. •

Bilateral swap arrangements between central banks. In a currency swap two central banks agree to exchange currency amounts, e.g. US dollars for euros. They agree on a fixed date in the future on which they will reverse the transaction applying the same exchange rate. During the term central banks can make foreign currency loans to private banks. •

IMF programmes and regional financing arrangements (e.g. European Stability Mechanism, Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation Agreement, BRICs CRA, Arab Monetary Fund, Latin American Reserve Fund). They make financial resources available to the members to tackle balance of payments difficulties, manage crises and prevent regional contagion effects. Depending on their design, they may impose conditions and requirements for economic policy measures on the recipient countries. Some regional programmes require a combination with IMF funds.

The most important element of the protection mechanisms: international reserves

International reserves are by far the largest element of the global safety net.12 The lack of predictability and robustness of other elements has led to an over-accumulation of reserves. After the Asian crisis, upper middle income countries in particular built up reserves. While China holds a major portion of the reserves in this group of countries, all other countries also boosted their reserves significantly. As a result of central bank interventions in the foreign exchange market, reserves have decreased since the year 2013.

The renaissance of bilateral swap arrangements

Bilateral swap arrangements were used by the US Treasury as early as in 1936 to supply developing countries with bridging loans. During the Bretton Woods period, the Fed introduced a network of swap lines known as reciprocal currency arrangements to prevent a sudden and substantial withdrawal of gold by official foreign institutions.13 A swap protected foreign central banks from the exchange rate risk when they had obtained excess and unwanted dollar positions. It allowed them to dispense with the temporary conversion of dollars into gold. Between 1973 and 1980, the swap lines were used instead of US currency reserves to finance interventions by the Fed in the foreign exchange market. Gains and losses were shared with the other central bank when the Fed drew on a line. However, the G10 central banks could try to use the swap arrangements to influence the US foreign currency market interventions, so the Fed stopped using them in the mid-1980s. All existing swap lines except those with Canada and Mexico were ended in 1998. After the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, the Fed established swap lines with the European Central Bank and the Bank of England for 30 days and expanded the existing line with the Bank of Canada. Currency swaps were used here for the first time to restore liquidity in financial markets. During the global financial crisis, the Fed then financed the lender-of-last-resort actions of other central banks in industrialised and emerging market economies, with the latter assuming the credit risk. The international reserves of many central banks at the start of the crisis were smaller than the amounts they borrowed under the swap lines. In 2013 the swap arrangements between the six most important central banks were converted into standing arrangements. All these swap arrangements have one thing in common: they signal the central banks’ willingness to cooperate with each other, whether it be in defence of the parities under the Bretton Woods system, to avert speculative attacks on the Fed, or with the aim of providing dollar liquidity during the financial crisis. China has also set up a far-reaching system of swap arrangements, mainly with the aim of pushing ahead with the internationalisation of the renminbi. But from the perspective of these central banks, the agreements with the Bank of England, the Monetary Authority of Singapore, the Reserve Bank of Australia and the ECB also serve the goal of being able to provide renminbi liquidity in their area of responsibility when needed Swaps represent a powerful and flexible tool of central banks that issue reserve currencies to regulate international capital flows. Central banks are the only institutions capable of changing their balance sheets quickly enough to keep pace with the volatility of international capital flows. Swaps are unsuitable, however, for longer-lasting crises, sovereign debt crises and to finance balance of payments imbalances. That is why they would be the most suitable tool for emerging market economies, as they are more likely to face abrupt changes in capital flows. Nevertheless, so far only the most important central banks that issue reserve currencies have been able to access unlimited swaps. Granting them is determined by the mandate of the central banks and they represent contractual, not institutional agreements. Accordingly, the central banks are able to choose their contractual partners, and there is no central independent authority to supervise swap arrangements. The swap arrangements for central banks in industrial countries that do not issue a reserve currency can therefore be expected to be reinstated in the event of a global shock, while they are less likely to be employed in case of a regional shock. Their use is even less predictable for systemic emerging market economies.

Growth of Global Financial Safety Net

Features of Instruments in the Global Financial Safety net

Use of GFSN in various shock Scenarios

- Balance of Payment shock

- Banking Sector FX Liquidity shock

- Sovereign Debt shock

US Dollar Swap Lines

These six central banks have permanent US Dollar swap lines since 2013.

- USA (Fed Reserve),

- Canada (BoC),

- Japan (BoJ),

- Switzerland (SNB),

- EU (ECB),

- UK(BOE)

During the global financial crisis, the Federal Reserve extended swap arrangements to 14 other central banks. The ECB drew very heavily, followed by the BoJ. At one point during the crisis in 2009, outstanding swaps amounted to more than $580 billion and represented about one-quarter of the Fed’s balance sheet. The novel element of this effort was the extension of swaps to four countries outside the usual set of advanced-country central banks: Mexico, Brazil, South Korea and Singapore.16 Mexico previously had a standing swap facility with the Federal Reserve by virtue of geographic proximity and the North American Free Trade Agreement, but the new arrangement expanded the amount that Mexico’s central bank could draw and the Fed’s swaps with Brazil, South Korea and Singapore broke new ground. The swaps in general were credited with preventing a more serious seizing up of interbank lending and financial markets during 2008 to 2009 (Helleiner 2014, 38–45; Prasad 2014, 202–11; IMF 2013a; 2014a, Box 2). The Federal Reserve board of governors considered the “boundary” question at length, torn between opening itself up to additional demands for coverage from emerging markets and creating stigma against those left outside the safety net. Fed officials used economic size and connections to international financial markets as the main criteria for selecting Brazil, Mexico, Singapore and South Korea. Chile, Peru, Indonesia, India, Iceland and likely others also requested swaps but were denied. The governors wanted to deflect requests by additional countries to the IMF, which coordinated its announcement of the SLF with the Fed’s announcement of the additional swaps at the end of October 2008. Governors and staff saw in this tiering a natural division of labour that coincided with the resources and analytical capacity of the Fed and IMF.17 The ECB extended swaps to Hungary, Poland, Sweden, Switzerland and Denmark, in addition to its arrangement with the United States. The BoJ extended swaps as well, notably to South Korea after the Federal Reserve announced its Korean swap. The PBoC began to conclude a set of swap agreements with Asian and non-Asian central banks that would eventually number more than 20 and amount to RMB 2.57 trillion. Only those swaps with the central banks of Hong Kong, Singapore and South Korea are known to have been activated (Zhang 2015, 5). Boosting the role of the renminbi in international trade was the express objective of these swaps, although their establishment also helped to secure market confidence during unsettled times. The proliferation of swaps resulted in a set of star-shaped networks of agreements among central banks that were linked by Fed liquidity (Allen and Moessner 2010). Although a number of the swaps in the network were activated, only those swaps of the Federal Reserve were heavily used during the crisis. The “fortunate four” emerging market countries among the Fed 14 were each covered for amounts up to $30 billion, but only temporarily. When the Fed later declined to renew the swaps, these countries became as vulnerable to liquidity shortfalls as the others. So, when South Korea took the chair of the G20 in 2010, its government proposed that the central bank swaps be multilateralized on a more permanent basis. It argued this would be increasingly necessary to stabilize the global financial system and would be in the interest of swap providers and recipients alike. Specifically, during the preparations for the G20 summit, South Korean officials proposed that the advanced-country central banks provide swaps to the IMF, which would conduct due diligence and provide liquidity to qualifying central banks. In this way, the global community could mobilize enough resources to address even a massive liquidity crunch and central banks would avoid credit risk.

In late 2013, six key-currency central banks made their temporary swap arrangements permanent standing facilities. Each central bank entered into a bilateral arrangement with the five others, comprising a network of 30 such agreements.18 But they prefer to maintain a constructive ambiguity with respect to whether they would re-extend swap arrangements to the other central banks that were covered during the global financial crisis, including Brazil, Mexico,19 South Korea and Singapore (Papadia 2013).

During the global financial crisis of 2008-2009, Federal Reserve extended USD swap lines to several central banks. The financial institutions in these countries faced USD shortages as the normal channels of money markets froze during crisis.

US Dollar Swap amounts extended during 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis

China RMB Swap Lines

During the 2007-8 global financial crisis, the international monetary system experienced an acute US dollar shortage that severely curtailed global trade and pressured international banking business (McCauley and McGuire, 2009; McGuire and von Peter, 2009). The US authorities, in response to the elevated strain in the global market, have arranged dollar swap lines with major central banks to mitigate the global dollar squeeze (Aizenman and Pasricha, 2010; Aizenman, Jinjarak and Park, 2011). On Thursday, October 31, 2013, the network of central banks comprises the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank, the Federal Reserve, and the Swiss National Bank agreed to convert their bilateral liquidity swap arrangements to standing arrangements until further notice.1 The dollar squeeze critically illustrated the danger of operating a US-centric global financial system. Against this backdrop, China has actively implemented measures of promoting the cross-border use of the Chinese currency, the renminbi (RMB), to reduce its reliance on the US dollar. The aggressive policy move was considered a clear signal of China’s efforts to internationalize RMB (Chen and Cheung, 2011; Cheung, Ma and McCauley, 2011). In 2009, China launched the scheme of cross-border trade settlement in RMB to encourage the denomination and settlement of international trade in its own currencies. One practical issue of settling trade in RMB is the limited availability of the currency outside China. China at that time had strict regulations on circulating the RMB across its border. To facilitate its RMB trade settlement initiative, China signed its first bilateral RMB local currency swap agreement with the Bank of Korea in December 2008, and the second one with Hong Kong in January 2009. Since then, China has signed various swap agreements with economies around the world.2

BRICS CRA

The 5th and 6th BRICS summits in 2013–2014 marked a watershed in the evolution of the BRICS group with the establishment of the first BRICS institutions. These included the BRICS New Development Bank, the CRA, the BRICS Business Council and the Think Tanks Council. Although this has weakened the ‘political talk shop’ perception of the group, critics have questioned whether these institutions will have a substantive effect. In particular, doubts have been cast upon the effectiveness of the CRA.

The CRA is modest in size in comparison to the IMF and other similar arrangements such as the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization (CMIM). At this stage the BRICS countries have committed $100 billion to the CRA, with China committing $41 billion, Russia, Brazil and India $18 billion each and South Africa $5 billion. The CMIM reportedly has a reserve pool of $240 billion and the IMF resources of $780 billion. It has been noted that with BRICS’s foreign reserves standing at about $5 trillion, a commitment of 16% would take the CRA pool to $800 billion.

From GLOBAL AND REGIONAL FINANCIAL SAFETY NETS: LESSONS FROM EUROPE AND ASIA

ASEAN +3 CMIM

ASEAN + Japan Korea China

The embryo of an Asian regional safety net arrangement has existed since 1977, when the five founding members of the ASEAN signed the ASEAN Swap Arrangement (ASA)5. Following the Asian crisis and after aborted discussion on the creation of an Asian Monetary Fund, Japan launched the New Miyazawa Initiative in October 1998 amounting to about $35 billion, which was targeted at stabilising the foreign exchange markets of Indonesia, the Republic of Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand6. The initiative was particularly valuable in containing instability in Malaysia’s financial sector, since that country had refused an IMF Stand-By Arrangement. The Japanese manoeuvre was deemed somewhat mutinous, since the IMF was very critical of Malaysia’s approach. But it also cemented the idea that Asia could gather enough resources to sandbag itself during a crisis period so long as Asian countries were united and managed to roll out timely and credible support mechanisms. In Asian countries under IMF programmes, the conditionality associated with the loans included severe fiscal cuts, deep structural reforms, and substantial increases in interest rates to stabilise currency markets. The economic and social cost of the adjustment was so high and abrupt that it provoked social unrest in a number of countries. This would reverberate strongly in the months that followed and leave a lasting scar in relations between Asian countries and the IMF7. This experience fuelled both a willingness to self-insure through accelerated reserve accumulation and to strengthen regional arrangements to reduce the reliance on global financial safety nets. Building on this lesson, the CMI was formalised in May 2000 during the ASEAN+3 Finance Ministers Meeting8. It largely built on the original ASA and bilateral swap agreements involving the PRC, Japan, and the Republic of Korea but was grounded in a broader programme that also included developing Asia’s local currency bond market and introduced a regional economic review and policy dialogue to enhance the region’s surveillance mechanism (Kawai and Houser 2007). The initiative included the new ASEAN members, increasing the total number of parties to the arrangement from 5 to 10. Table A.1 in the appendix highlights the evolution of the CMI. The question of cooperation between the CMI and the IMF quickly became quite heated, with a number of countries arguing that strong ties to the Fund would defeat the initial purpose of the initiative (Korea Institute of Finance, 2012), but the ties were kept nonetheless both to mitigate moral hazard (Sussangkarn, 2011) and to ensure some consistency with conditionality attached to the IMF’s own programmes. After the formal creation of the CMI in 2000, the era of Great Moderation that followed to some degree doused further ambitions to strengthen regional arrangements. As a result, when the global financial crisis hit in 2008, the Asian regional financial safety net proved too modest to play a meaningful role.

Indeed, instead of seeking support under CMI, the Bank of Korea and the Monetary Authority of Singapore sought a swap agreement with the US Federal Reserve for some $30 billion each. The Republic of Korea concluded bilateral agreements with Japan and the PRC that were not related to the CMI. Similarly, Indonesia established separate bilateral swap lines with Japan and the PRC to shore up its crisis buffer and did not resort to the CMI for credit support (Sussangkarn, 2011). The plan to consolidate the bilateral swap arrangements and form a single, more solid, and effective reserve pooling mechanism – which had initially been put forward by the finance ministers of the ASEAN+3 in May 2007 in Kyoto – was accelerated and evolved in several iterations before the final version was laid out more than two years later. In December 2009, the CMI was multilateralised and the ASEAN+3 representatives signed the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation (CMIM) Agreement, which effectively became binding on March 24, 2010 (BSP, 2012). These successive transformations have strengthened the initiative, but it remains largely untested. In addition, other aspects of any credible regional financial arrangement, such as surveillance capacity and coordination of some basic economic policies, remain relatively embryonic.

From GLOBAL AND REGIONAL FINANCIAL SAFETY NETS: LESSONS FROM EUROPE AND ASIA

EU ESM

The history of European financial safety nets cannot be dissociated from the history of European monetary integration. With this perspective in mind, it dates back to the late 1960s and has been an ongoing debate to this day. The history of European political integration at every turn is marked by failed projects or actual mechanisms of financial solidarity, ranging from loose exchange rate arrangements to the project of a full-fledged European Monetary Fund. The advent of the monetary union was precisely designed to reduce the need for financial safety nets within the euro area. But the architectural deficiencies of the euro area and the lack of internal transfers have required the establishment of alternative mutual insurance mechanisms since the onset of the euro crisis in 2010. In 2008, when the global financial crisis hit, Hungary had accumulated important external imbalances and large foreign exchange exposures. It had to seek financial assistance almost immediately and initiated contacts with the IMF. The total absence of coordination with European authorities came as an initial shock because it showed that despite decades of intense economic, political, and monetary integration, EU countries could still come to require international financial assistance. The experience pushed European institutions to unearth a forgotten provision of the Maastricht Treaty to provide financial assistance through the Balance of Payments Assistance Facility9. This created preliminary and at first ad-hoc coordination between the IMF and the European Commission, which was then rediscovering design and monitoring of macroeconomic adjustment programmes. Despite the rapid use of this facility and the emergence of a framework of cooperation with the IMF, contagion from the global financial crisis continued for months and prompted some Eastern European leaders to seek broader and more pre-emptive support10, which failed. However, beyond official sector participation, there was a relatively rapid realisation that cross-border banking and financial retrenchment could become a major source of financial disruption and effectively propagate the crisis further – including back to the core of Europe, as large European banks were heavily exposed to Eastern Europe through vast and dense networks of branches and subsidiaries. In response, in late February 2009, under the leadership of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the World Bank decided to establish what was known as the Vienna Initiative. This was designed as a joint multilateral and private sector coordination and enforcement mechanism to reduce the risk of banking sector sudden stops. In particular, it compelled cross-border European banks to continue to provide appropriate liquidity to their branches and subsidiaries in Central and Eastern Europe. The formalisation of such an arrangement11 quite early in the crisis has certainly proven the case for coordination of financial institutions in emerging-market economies, especially when a relatively small number of institutions have a disproportionate impact on capital flows. But with the crisis spreading to the euro area, starting with Greece in the fall of 2010, new regional arrangements proved necessary. The lack of instruments forced European officials to first consider bilateral assistance from member states. The idea of involving the IMF was initially violently rejected 9 on intellectual and political grounds12 but proved inevitable. In a number of successive iterations, more solid regional arrangements were designed (Bijlsma and Vallée 2012). Table A.2 in the appendix shows the evolution of European regional financial safety nets.

List of Regional Financial Agreements (RFA)

Key Terms:

- RMB

- Bilateral Currency Swaps

- Reserve Pooling

- CMI

- CMIM

- BRICS CRA

- AMRO

- IMF SDR Basket

- Currency Internationalization

- Global Liquidity

- Funding Liquidity

- Market Liquidity

- BRICS NDB

- CHINA AIIB

- Regional Integration

- Multilateralism

- Multipolar

- FX Swap Networks

- Central Banks

- Reserve Currency

- Global Financial Safety Nets (GFSN)

- Foreign Exchange Reserves

- Regional Financial Agreements (RFA)

- Regional Financial Networks (RFN)

- Bilateral Currency Swap Agreement (BSA)

- RMB (Renminbi also known as Yuan)

- International Lender of Last Resort (ILOLR)

- Regional Financial Safety Net (RFSN)

- Multilateral Financial Safety Net (MFSN)

- National Financial Safety Net (NFSN)

Key Sources of Research:

Self-Insurance, Reserve Pooling Arrangements, and Pre-emptive Financing

Sunil Sharma

Regional Reserve Pooling Arrangements

Suman S. Basu Ran Bi

Prakash Kannan

First Draft: 8 February, 2010 This Draft: 7 June, 2010

Toward a functional Chiang Mai Initiative

15 May 2012

Author: Chalongphob Sussangkarn, TDRI

http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2012/05/15/toward-a-functional-chiang-mai-initiative/

The International Financial Architecture and the Role of Regional Funds

Barry Eichengreen

University of California, Berkeley

August 2010

Click to access intl_finan_arch_2010.pdf

Examining the case for Reserve Pooling in East Asia: Empirical Analysis

Ramkishen S. Rajan, Reza Siregar and Graham Bird

2003

Financial Architectures and Development: Resilience, Policy Space and Human Development in the Global South

by Ilene Grabel

2013

Click to access hdro_1307_grabel.pdf

International reserves and swap lines: substitutes or complements?

Joshua Aizenman,

Yothin Jinjarak, and Donghyun Park,

March 2010

Click to access ajp-ir-sw-0301.pdf

How can we fix the global financial safety net?

WEF

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/10/how-can-we-fix-the-global-financial-safety-net/

Regional Monetary Cooperation: Lessons from the Euro Crisis for Developing Areas?

Sebastian Dullien

Barbara Fritz

Laurissa Mühlich

Click to access WEA-WER2-Dullien.pdf

The Global Dollar System

Stephen G Cecchetti

The Future of the IMF and of Regional Cooperation in East Asia

Yung Chul Park, Charles Wyplosz

2008

Click to access 20081111-12_Y-C_Park-C_Wyplosz.pdf

China’s Bilateral Currency Swap Agreements: Recent Trends

Aravind Yelery

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0009445515627210

The Spread of Chinese Swaps

CFR

Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization

The Chiang Mai Initiative

Beyond the Chiang Mai Initiative: Prospects for Regional Financial and Monetary Integration in East Asia

Click to access Session-2_1-4.pdf

Currency internationalisation: an overview

Peter B Kenen

Click to access arpresearch200903.01.pdf

Why Was the CMI Possible?

Embedded Domestic Preferences and Internationally Nested Constraints in Regional Institution Building in East Asia

Saori N. Katada

Click to access 1f1966fe-1c48-4d32-a463-ea268ecb2903.pdf

Emergent International Liquidity Agreements: Central Bank Cooperation after the Global Financial Crisis

Daniel McDowell

Click to access mcdowell_eln.pdf

Regional Financial Cooperation in Asia

Daikichi Momma

Click to access Session_2_Momma.pdf

East Asian Economic Cooperation and Integration: Japan’s Perspective

Takatoshi Ito

Click to access 41RegionalCoop.pdf

What Motivates Regional Financial Cooperation in East Asia Today?

JENNIFER AMYX

http://www.eastwestcenter.org/system/tdf/private/api076.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=32049

Evaluating Asian Swap Arrangements

Joshua Aizenman, Yothin Jinjarak, and Donghyun Park

No. 297 July 2011

Click to access adbi-wp297.pdf

Regional Monetary Cooperation in East Asia Should the United States Be Concerned?

Wen Jin Yuan Melissa Murphy

Click to access 101129_Yuan_RegionalCoop_WEB.pdf

Chiang Mai Initiative as the Foundation of Financial Stability in East Asia

COMPLEX DECISION IN THE ESTABLISHMENT OF ASIAN REGIONAL FINANCIAL ARRANGEMENT

Iwan J Azis

Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization

December 2013

Click to access ChiangMaiInitiative_0.pdf

RMBI or RMBR?

Is the Renminbi Destined to Become a Global or Regional Currency?

Barry Eichengreen

Domenico Lombardi

Click to access RMBI_or_RMBR_-_Eichengreen.pdf

Monetary and financial cooperation in Asia: taking stock of recent ongoings

Ramkishen S. Rajan

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.473.361&rep=rep1&type=pdf

FINANCIAL CRISES AND EAST ASIA’S FINANCIAL COOPERATION

By Park Young-joon

MONETARY INTEGRATION IN EAST ASIA

Peter B. Kenen

Ellen E. Meade

Regional cooperation for financial and exchange rates stability in East Asia

Kenichi Shimizu

Click to access WP_FG7_2013_01_Dezember_Kenichi_Shimizu.pdf

ASIAN FINANCIAL CO-OPERATION

Address by Mr GR Stevens

The Rise of China and Regional Integration in East Asia

REGIONAL FINANCIAL COOPERATION IN EAST ASIA: THE CHIANG MAI INITIATIVE AND BEYOND

Click to access Bulletin02-ch8.pdf

Financial RegionaliSm: a Review oF the iSSueS

Domenico lombaRDi

2010

Click to access 11_global_economy_lombardi.pdf

The layers of the global financial safety net: taking stock

2016

Click to access eb201605_article01.en.pdf

Regional Financial Arrangements for East Asia: A Different Agenda from Latin America

By Yung Chul Park

Elasticity and Discipline in the Global Swap Network

Perry Mehrling

Working Paper No. 27 November 12, 2015

Click to access WP27-Mehrling.pdf

Swap Agreements & China’s RMB Currency Network

https://www.cogitasia.com/swap-agreements-chinas-rmb-currency-network/

Central Bank Currency Swaps and the International Monetary System

Christophe Destais

Click to access CentralBankCurrencySwap_ChristopheDestais.pdf

Renminbi internationalisation – The pace quickens

Click to access Renminbi-internationalisation-The-pace-quickens.pdf

What Will China’s RMB Bilateral Currency Swap Deals Lead To?

Emergent International Liquidity Agreements: Central Bank Cooperation after the Global Financial Crisis

Daniel McDowell

Click to access mcdowell_eln.pdf

Currency Swap of Central Bank: Influence on International Currency System

Click to access 20160316142214_202.pdf

Building Global and Regional Financial Safety Nets

February 2016

Yung Chul Park

RMBI or RMBR?

Is the Renminbi Destined to Become a Global or Regional Currency?

Barry Eichengreen

Domenico Lombardi

Click to access RMBI_or_RMBR_-_Eichengreen.pdf

China’s Bilateral Currency Swap Lines

Yin-Wong Cheung, Hung Hing Ying LIN Zhitao

ZHAN Wenjie

2016

Click to access GRU%232016-013%20_YW.pdf

Internationalisation of the Chinese Currency: Towards a Multipolar International Monetary System?

Lucia Országhová

Click to access biatec_01_2016_orszaghova.pdf

Central bank: China currency swap deals surpass 3t yuan

http://english.gov.cn/state_council/ministries/2015/06/11/content_281475125318660.htm

The International Lender of Last Resort for Emerging Countries: A Bilateral Currency Swap?

Camila Villard Duran

Entry of yuan into SDR may give a boost to global liquidity

Redback Rising: China’s Bilateral Swap Agreements and RMB Internationalization

Steven Liao

Daniel E. McDowell

International reserves and swap lines: substitutes or complements?

Joshua Aizenman

Yothin Jinjarak, Donghyun Park

March 2010

Click to access ajp-ir-sw-0301.pdf

The Asian Monetary Fund Reborn? Implications of Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization

William W. Grimes

2011

Avoiding the next liquidity crunch: how the G20 must support monetary cooperation to increase resilience to crisis

Camila Villard Duran

Click to access GEG%20Villard%20Duran%20October%202015.pdf

Stitching together the global financial safety net

Edd Denbee, Carsten Jung and Francesco Paternò

2016

Click to access fs_paper36.pdf

Why Are There Large Foreign Exchange Reserves? The Case of South Korea

Franklin Allen

Joo Yun Hong

Click to access 01_KSSJ_11-02-03.pdf

Federal Reserve Policy in an International Context

Ben S. Bernanke

The dollar’s international role: An “exorbitant privilege”?

Ben S. Bernanke

Thursday, January 7, 2016

TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT REPORT, 2015

Making the international financial architecture work for development

Click to access tdr2015ch3_en.pdf

Global Economic Governance in Asia: Through the Looking Glass of the European Sovereign Debt Crisis

China in Global Financial Governance: Implications from Regional Leadership Challenge in East Asia

Takashi Terada

Central Bank Currency Swaps Key to International Monetary System

http://andrewsheng.net/Article_Central_bank_currency_swaps_key_to_IMS.html

The Federal Reserve’s Foreign Exchange Swap Lines

Michael J. Fleming and Nicholas J. Klagge

Central Bank Liquidity Swaps

https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/liquidity_swap.html

Central Bank Dollar Swap Lines and Overseas Dollar Funding Costs

Linda S. Goldberg, Craig Kennedy, and Jason Miu

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.422.11&rep=rep1&type=pdf

eXperience With foreign currency liquidity-providing centrAl bAnK sWAps

Click to access art1_mb201408_pp65-82en.pdf

Banking on China through Currency Swap Agreements

October 23, 2015

By Cindy Li

TESTING THE GLOBAL CENTRAL BANK SWAP NETWORK

http://www.perrymehrling.com/2015/07/testing-the-global-central-bank-swap-network/

The impact of international swap lines on stock returns of banks in emerging markets

Alin Marius Andries1 Andreas M. Fischer2 Pınar Ye ̧sin

June 2015

Click to access sem_2015_07_09_Andries_Fischer_Yesin.n.pdf

Why Did the US Federal Reserve Unprecedentedly Offer Swap Lines to Emerging Market Economies during the Global Financial Crisis? Can We Expect Them Again in the Future?

Hyoung-kyu Chey

International reserves and swap lines: substitutes or complements?

Joshua Aizenman,

Yothin Jinjarak, Donghyun Park

July 2010

Click to access 037b0b0312cfb51cee7dffd5c3399332a669.pdf

Central Bank Dollar Swap Lines and Overseas Dollar Funding Costs

Linda S. Goldberg Craig Kennedy Jason Miu

Click to access 9a564d30e508dcd3799ceb7a99b5e2c2e273.pdf

Central Bank Liquidity Swaps

Central bank currency swaps key to international monetary system

April 2014

Author: Andrew Sheng, Fung Global Institute

Evaluating Asian Swap Arrangements

Joshua Aizenman, Yothin Jinjarak, and Donghyun Park

No. 297 July 2011

Click to access adbi-wp297.pdf

Central Bank Liquidity Swaps Overview

Yubo Wang

February 15, 2010

Click to access Central_Bank_Liquidity_Swaps_201002.pdf

The implications of cross-border banking and foreign currency swap lines for the international monetary system

Már Guðmundsson:

Click to access MGpresentation.pdf

The Politics of Rescuing the World’s Financial System: The Federal Reserve as a Global Lender of Last Resort

J. Lawrence Broz

2014

From Exorbitant Privilege to Existential Trilemma

The dollar is now everyone’s problem

September 29, 2014

http://www.moneyandbanking.com/commentary/2014/9/29/the-dollar-is-now-everyones-problem

The Global Dollar System

Stephen G Cecchetti

Central Bank Swaps and International Dollar Illiquidity

Andrew K. Rose Mark M. Spiegel∗

March 14, 2012

DOLLAR FUNDING AND THE LENDING BEHAVIOR OF GLOBAL BANKS

VICTORIA IVASHINA DAVID S. SCHARFSTEIN JEREMY C. STEIN

First draft: October 2012 This draft: March 2015

Click to access ISS%20revision%20march%202015%20FINAL_7529aa88-fe19-4fd1-8427-43b83c5d8589.pdf

THE INTERNATIONALIZATION OF THE RENMINBI AND THE RISE OF A MULTIPOLAR CURRENCY SYSTEM

By Miriam Campanella

Click to access WP201201_1.pdf

Dollar Illiquidity and Central Bank Swap Arrangements During the Global Financial Crisis

Andrew K. Rose Mark M. Spiegel

August 2011

Central Bank Dollar Swap Lines and Overseas Dollar Funding Costs

Linda S. Goldberg, Craig Kennedy, Jason Miu

US Dollar Swap Arrangements between Central Banks

Currency Swaps with Foreign Central Banks

BY RENEE COURTOIS

Click to access policy_update.pdf

Central Banks Make Swaps Permanent as Crisis Backstop

Jeff Black

October 31, 2013

Swap Lines Underscore the Dollar’s Global Role

Click to access 12q1currencyswaps.pdf

Central bank co-operation and international liquidity in the financial crisis of 2008-9

by William A Allen and Richhild Moessner

Monetary and Economic Department

May 2010

Financial instability, Reserves, and Central Bank Swap Lines in the Panic of 2008

Maurice Obstfeld Jay C. Shambaugh Alan M. Taylor

Click to access ObstfeldShambaughTaylorAEAPP.pdf

The Federal Reserve as Global Lender of Last Resort, 2007-2010

J. Lawrence Broz

Lenders of Last Resort and Global Liquidity

Rethinking the system

Click to access outreach_obstfeld_dec09.pdf

The Fed’s FX swap facilities have been quiet… too quiet?

Swap Lines Underscore the Dollar’s Global Role

Click to access 12q1currencyswaps.pdf

THE EVOLUTION OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SWAP LINES SINCE 1962

Michael D. Bordo Owen F. Humpage Anna J. Schwartz

2014

How China Covered The World In “Liquidity Swap Lines”

http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2015-05-17/how-china-covered-world-liquidity-swap-lines

The Federal Reserve’s Foreign Exchange Swap Lines

Michael J. Fleming Nicholas Klagge

April 1, 2010

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers2.cfm?abstract_id=1597320

The Federal Reserve as Global Lender of Last Resort, 2007-2010

J. Lawrence Broz

The Fed’s Role in International Crises

Donald Kohn

Thursday, September 18, 2014

https://www.brookings.edu/on-the-record/the-feds-role-in-international-crises/

Options for meeting the demand for international liquidity during financial crises

The Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization: Origin, Development and Outlook

Chalongphob Sussangkarn

No. 230 July 2010

Click to access adbi-wp230.pdf

The Amended Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation (CMIM) Comes Into Effect on July 17, 2014

Click to access rel140717a.pdf

Note on Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization (CMIM)*

Chalongphob Sussangkarn

Click to access Chalongphabs_Note.pdf

SOURCES AND EVOLUTION OF THE CHIANG MAI INITIATIVE

Vyacheslav Amirov

The Chiang Mai Initiative

PIIE

Why Was the CMI Possible?

Embedded Domestic Preferences and Internationally Nested Constraints in Regional Institution Building in East Asia**

Saori N. Katada

Click to access 1f1966fe-1c48-4d32-a463-ea268ecb2903.pdf

From the Chiang Mai Initiative to an Asian Monetary Fund

Masahiro Kawai

No. 527 May 2015

Click to access adbi-wp527.pdf

Asian Monetary Fund: Getting Nearer

By Pradumna B. Rana

Panel on Financial Affairs Meeting on 2 November 2009

Background Brief

on Hong Kong’s participation in Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization

Click to access fa1102cb1-144-e.pdf

The Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation: Origin, Development and Outlook

Chalongphob Sussangkarn

Much Ado about Nothing? Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation and East Asian Exchange Rate Cooperation

Wolf HASSDORF

Click to access 06Hassdorf.pdf

Financial Safety Nets in Asia: Genesis, Evolution, Adequacy, and Way Forward

Hal Hill and Jayant Menon

Click to access wp_econ_2012_17.pdf

Financial Community Building in East Asia

The Chiang Mai Initiative: Its Causes and Evaluation

EPIK 2010 Economics of Community Building

Yoon Jin Lee

Click to access YoonJinLee.pdf

FROM “TAOGUANG YANGHUI” TO “YOUSUO ZUOWEI”:

CHINA’S ENGAGEMENT IN FINANCIAL MINILATERALISM

HONGYING WANG

Click to access cigi_paper_no52.pdf

Foundation of Regional Integration: Common or Divergent Interests?

Yong Wook Lee

Click to access 이용욱-_foundation_of_regional_integration__1_.pdf

CMIM and ESM: ASEAN+3 and Eurozone Crisis Management and Resolution Liquidity Provision in Comparative Perspective

Ramon PACHECO PARDO

Click to access CBFL-WP-RPP01.pdf

An Overview of Regional Financial Cooperation: Implication for BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement

Zhang Liqing,NianShuting

Click to access 20160316142109_641.pdf

CMIM-Asian Multilateralism and Cooperation

Keynote speech by Dr. Junhong Chang, AMRO Director, at the 6th Asia Research Forum

1 July 2016

Financial RegionaliSm: a Review oF the iSSueS

Domenico lombaRDi

Click to access 11_global_economy_lombardi.pdf

Practices of Financial Regionalism and the Negotiation of Community in East Asia

Mikko Huotari

Click to access op8_huotari_feb-2012_end.pdf

Financial Integration in Emerging Asian Economies

Gladys Siow

Click to access 032-ICEBI2012-A10048.pdf

Regional Monetary Cooperation: Lessons from the Euro Crisis for Developing Areas?

Sebastian Dullien

Barbara Fritz

Laurissa Mühlich

Click to access WEA-WER2-Dullien.pdf

The Need and Scope for Strengthening Co-operation Between Regional Financing Arrangements and the IMF

Ulrich Volz

Click to access DP_15.2012.pdf

Towards institutionalization: The BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA)

The BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement and its Position

in the Emerging Global Financial Architecture

NIColETTE CATTANEo, MAyAMIko BIzIwICk & DAvID FRyER

Financial Architectures and Development:

Resilience, Policy Space and Human Development in the Global South

by Ilene Grabel

Click to access hdro_1307_grabel.pdf

Financial Regionalism in East Asia

Enhancing the Effectiveness of CMIM and AMRO: Selected Immediate Challenges and Tasks

Reza Siregar and Akkharaphol Chabchitrchaidol

No. 403 January 2013

Click to access 2013.01.17.wp403.enhancing.effectiveness.cmim_.amro_.pdf

Regional and Global Liquidity Arrangements

Ulrich Volz / Aldo Caliari (Editors)

Click to access regional_funds_oct2010.pdf

A regional reserve fund for Latin America

Daniel Titelman, Cecilia Vera, Pablo Carvallo and Esteban Pérez Caldentey

Click to access RVI112Titelmanetal_en.pdf

Financial Crises as Catalysts for Regional Integration? The Chances and Obstacles for Monetary Integration in ASEAN+3 and MERCOSUR

Sebastian Krapohl Daniel Rempe

Click to access KrapohlRempe.pdf

Financial Integration

Click to access Financial%20Integration.pdf

Framework of the ASEAN Plus Three Mechanisms Operating in the Sphere of Economic Cooperation

Prof. Dr. Vyacheslav V. Gavrilov

Click to access CALE20DP20No.207-110826.pdf

Regional Integration in Europe and East Asia: Experiences of Integration and Lessons from Functional Multilateralism

Uwe Wissenbach

Click to access 13-2-02_Uwe_Wissenbach.pdf

General Overview: “Financial Risk and Crisis Management after the Global Financial Crisis”

Click to access Jun2016No9.pdf

Remaking the architecture: the emerging powers, self-insuring and regional insulation

GREGORY T. CHIN

The Origins and Transformation of East Asian Financial Regionalism

Regional Financial Arrangement: An Impetus for Regional Policy Cooperation

Reza Siregar and Keita Miyaki

Click to access MPRA_paper_51050.pdf

Role of Regional Institutions in East Asia

Click to access RPR_FY2011_No.10_Chapter_11.pdf

Asia’s new financial safety net: Is the Chiang Mai Initiative designed not to be used?

Hal Hill, Jayant Menon

25 July 2012

http://voxeu.org/article/chiang-mai-initiative-designed-not-be-used

Will the new BRICS institutions work?

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2014/08/brics-new-development-bank-contingent-reserve-agreement/

BRICS NEW DEVELOPMENT BANK AND CONTINGENT RESERVE ARRANGEMENT

Click to access 150428BRICS_Bank.pdf

The Contingent Reserve Arrangement and the International Monetary System

Manmohan Agarwal

Click to access 2ead896b5e52456a098bbd2d0b25774b.pdf

The BRICS Bank and Reserve Arrangement: towards a new global financial framework?

2014

Click to access EPRS_ATA(2014)542178_REV1_EN.pdf

China’s Bilateral Currency Swap Lines

Lin Zhitao Zhan Wenjie Yin-Wong Cheung

CESIFO WORKING PAPER NO. 5736 CATEGORY 7:MONETARY POLICY AND INTERNATIONAL FINANCE JANUARY 2016

Elasticity and Discipline in the Global Swap Network

Perry Mehrling Barnard College and INET

November 6, 2015

A Proposal for a New Regional Financial Arrangement: The Reserve Liquidity Line

Young-Joon Park

2014

International Liquidity in a Multipolar World

Barry Eichengreen

International Liquidity Swaps: Is the Chiang Mai Initiative Pooling Reserves Efficiently ?

Emanuel Kohlscheen and Mark P. Tayl

Click to access liquidity_swaps.pdf

International Reserves and Swap Lines in Times of Financial Distress: Overview and Interpretations

Joshua Aizenman

No. 192 February 2010

Click to access adbi-wp192.pdf

Coordinating Regional and Multilateral Financial Institutions

C. Randall Henning

The Asian Monetary Fund Reborn? Implications of Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization

William W. Grimes

REGIONAL LIQUIDITY MECHANISMS IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

Gustavo Rojas de Cerqueira César

Click to access PWR_v4_n3_Regional.pdf

Much Ado about Nothing? Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation and East Asian Exchange Rate Cooperation

Wolf HASSDORF

Click to access 06Hassdorf.pdf

Global Liquidity: Public and Private

Jean-Pierre Landau

Click to access Jackson-Hole-Print.pdf

Safety for whom? The scattered global financial safety net and the role of regional financial arrangements

Mühlich, Laurissa; Fritz, Barbara

The International Financial Architecture and the Role of Regional Funds

Barry Eichengreen

August 2010

Click to access intl_finan_arch_2010.pdf

The evolving multi-layered global financial safety net : role of Asia

Pradumna B. Rana

2012

https://dr.ntu.edu.sg/bitstream/handle/10220/9109/WP238.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

The decentralised global monetary system requires an efficient safety net

Click to access Fokus-Nr.-147-November-2016-monetäres-System_EN.pdf

Asian Regional Financial Safety Nets? Don’t Hold Your Breath

Iwan J Azis

STITCHING TOGETHER THE GLOBAL FINANCIAL SAFETY NET

Minouche Shafik,

Deputy Governor, Bank of England

26th February 2016

The Global Financial Safety Net through the Prism of G20 Summits

Gong Cheng

European Stability Mechanism

ADEQUACY OF THE GLOBAL FINANCIAL SAFETY NET

Pradumna B. Rana

The Global Liquidity Safety Net

Institutional Cooperation on Precautionary Facilities and Central Bank Swaps

Inadequate Regional Financial Safety Nets Reflect Complacency

Iwan J. Azis

No. 411 March 2013

Click to access adbi-wp411.pdf

Stitching together the global financial safety net

by Edd Denbee, Carsten Jung and Francesco Paternò

Click to access QEF_322_16.pdf

GLOBAL AND REGIONAL FINANCIAL SAFETY NETS: LESSONS FROM EUROPE AND ASIA

CHANGYONG RHEE, LEA SUMULONG AND SHAHIN VALLÉE

Click to access WP_2013_02.pdf

Financial Safety Nets in Asia: Genesis, Evolution, Adequacy, and Way Forward

Hal Hill and Jayant Menon

No. 395 November 2012

Beatrice Scheubel, Livio Stracca

04 October 2016

Global Financial Safety Nets: Where Do We Go from Here?

Eduardo Fernandez-Arias

Eduardo Levy Levy-Yeyati

November 2010

How can countries cooperate to mitigate contagion and limit the spread of crises?November 7, 2011

What do we know about the global financial safety net? Rationale, data and possible evolution

3 thoughts on “Global Financial Safety Net: Regional Reserve Pools and Currency Swap Networks of Central Banks”