Production Chain Length and Boundary Crossings in Global Value Chains

From Structure and length of value chains

In a value chain, value is added in sequential production stages and is carried forward from one producer to the next in the form of intermediate inputs. Value chains driven by the fragmentation of production are not an entirely new economic phenomenon, but the increasing reliance on imported intermediate inputs makes value chains global.

According to a 2013 report by the OECD, WTO and UNCTAD for the G-20 Leaders Summit, “Value chains have become a dominant feature of the world economy” (OECD et al., 2013).

Obviously, this dominant feature of the world economy needs measuring and analyzing. Policy-relevant questions include, but are not limited to:

- what is the contribution of global value chains to economy GDP and employment? how long and complex are value chains?

- what is the involvement and position of individual industries in global value chains? do multiple border crossings in global value chains really matter?

These and related questions generated a considerable amount of investigations proposing new measures of exports and production to account for global value chains. Some of those were designed to re-calculate trade flows in value added terms, whereas other provided an approximation of the average length of production process.

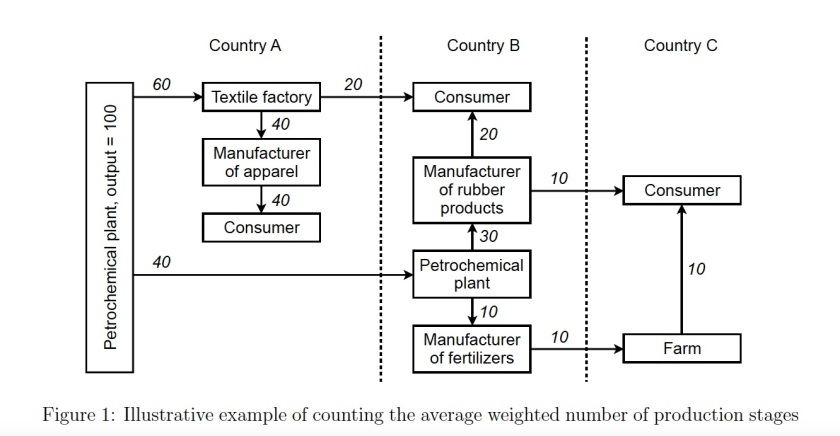

A relatively new stream of research focuses on a deep decomposition of value added or final demand ( rather than exports or imports ) into components with varied paths along global value chains and measurements of the length of the related production processes. Consider, for example, a petrochemical plant that generates some value added equal to its output less all intermediate inputs used. We would be interested to know which part of this value added, embodied in the petrochemicals, is used entirely within the domestic economy and which part is exported.

We would also inquire how much of the latter satisfies final demand in partner countries and how much is further used in production and, perhaps, in exports to third countries and so on. We would be interested, in particular, in counting the number of production stages the value added in these petrochemicals passes along the chain before reaching its final user.

From Structure and length of value chains

From Structure and length of value chains

A natural question is whether this method can be applied to the real economy with myriads of products, industries and dozens of partner countries? It can surely be applied if the data on inter-industry transactions are organized in the form of input-output accounts, and the computations are performed in block matrix environment. In fact, the measurement of the number of production stages or the length of production chains has attracted the interest of many input-output economists. The idea of simultaneously counting and weighting the number of inter-industry transactions was formalized by Dietzenbacher et al. (2005). Their “average propagation length” (APL) is the average number of steps it takes an exogenous change in one industry to affect the value of production in another industry. It is the APL concept on which we build the count of the number of production stages from the petrochemical plant to its consumers in our simplified example above. The only difference is that Dietzenbacher et al. (2005), and many authors in the follow-up studies, neglect the completion stage. First applications of the APL concept to measure the length of cross-border production chains appear in Dietzenbacher and Romero (2007) and Inomata (2008), though Oosterhaven and Bouwmeester (2013) warn that the APL should only be used to compare pure interindustry linkages and not to compare different economies or different industries.

Fally (2011, 2012) proposes the recursive definitions of two indices that quantify the “average number of embodied production stages” and the “distance to final demand”. Miller and Temurshoev (2015), by analogy with Antras et al. (2012), use the logic of the APL and derive the measures of “output upstreamness” and “input downstreamness” that indicate industry relative position with respect to the nal users of outputs and initial producers of inputs. They show that their measures are mathematically equivalent to those of Fally and the well known indicators of, respectively, total forward linkages and total backward linkages. Fally (2012) indicates that the average number of embodied production stages may be split to account for the stages taking place within the domestic economy and abroad. This approach was implemented in OECD (2012), De Backer and Miroudot (2013) and elaborated in Miroudot and Nordstrom (2015).

Ye et al. (2015) generalize previous length and distance indices and propose a consistent accounting system to measure the distance in production networks between producers and consumers at the country, industry and product levels from different economic perspectives. Their “value added propagation length” may be shown to be equal to Fally’s embodied production stages and Miller & Temurshoev’s input downstreamness when aggregated across producing industries.

Finally, Wang et al. (2016) develop a technique of additive decomposition of the average production length. Therefore, they are able to break the value chain into various components and measure the length of production along each component. Their production length index system includes indicators of the average number of domestic, cross-border and foreign production stages. They also propose new participation and production line position indices to clearly identify where a country or industry is in global value chains. Importantly, Wang et al. (2016) clearly distinguish between average production length and average propagation length, and between shallow and deep global value chains.

This paper builds on the technique and ideas of Wang et al. (2016) and the derivation of the weighted average number of border crossings by Muradov (2016). It re-invents a holistic system of analytical indicators of structure and length of value chains. As in Wang et al. (2016), global value chains are treated here within a wider economy context and are juxtaposed with domestic value chains. This enables developing new indices of orientation towards global value chains. The novel deliverables of this paper are believed to include the following. First, all measurements are developed with respect to output rather than value added or final product flows. This is superior for interpretation and visualization purposes because a directly observable economic variable ( output ) is decomposed in both directions, forwards to the destination and backwards to the origin of value chain. It is also shown that at a disaggregate country-industry level, the measurement of production length is equivalent with respect to value added and output. Second, the decomposition of output builds on a factorization of the Leontief and Ghosh inverse matrices that allows for an explicit count of production stages within each detailed component. Third, the system builds on a refined classication of production stages, including final and primary production stages that are often neglected in similar studies. Fourth, the paper re-designs the average production line position index and proposes new indices of orientation towards global value chains that, hopefully, avoid overemphasizing the length of some unimportant cross-border value chains. Fifth, a new chart is proposed for the visualization of both structure and length of value chains. The chart provides an intuitive graphical interpretation of the GVC participation, orientation and position indices.

It is also worth noting that both Wang et al. (2016) and this paper propose similar methods to estimate the intensity of GVC-related production in partner countries and across borders. This is not possible with previous decomposition systems without explicitly counting the average number of production stages and border crossings.

Key Terms:

- Average Propagation Length

- National Boundaries

- Networks

- Value Chains

- Supply Chains

- Upstreamness

- Downstreamness

- Structure of Chains

- Smile Curves

- Vertical Specialization

- Fragmentation of Production

- Shock Amplifiers

- Shock Absorbers

- Production Sharing

- World Input Output Chains

- WIOD

- Counting Boundary Crossings

- Production Staging

- Slicing Up Value Chains

- Mapping Value Chains

- Geography of Value Chains

- Spatial Economy

Key Sources of Research:

Characterizing Global Value Chains

Zhi Wang

Shang-Jin Wei

Xinding Yu and Kunfu Zhu

GLOBAL VALUE CHAIN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2016

Background Paper Conference

Beijing, 17-18 March 2016

Click to access Characterizing_Global_Value_Chains.pdf

The Great Trade Collapse: Shock Amplifiers and Absorbers in Global Value Chains

Zhengqi Pan

2016

Click to access Zhengqi%20Pan_GPN2016_008.pdf

CHARACTERIZING GLOBAL VALUE CHAINS:PRODUCTION LENGTH AND UPSTREAMNESS

Zhi Wang

Shang-Jin Wei

Xinding Yu

Kunfu Zhu

March 2017

Characterizing Global Value Chains

Zhi Wang

Shang-Jin Wei,

Xinding Yu and Kunfu Zhu

September 2016

Click to access Wang,%20Zhi.pdf

MEASURING AND ANALYZING THE IMPACT OF GVCs ON ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

GLOBAL VALUE CHAIN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2017

International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank

2017

Click to access tcgp-17-01-china-gvcs-complete-for-web-0707.pdf

Global Value Chains

Click to access Lecture%20Global%20Value%20Chains.pdf

MAPPING GLOBAL VALUE CHAINS

4-5 December 2012

The OECD Conference Centre, Paris

Click to access MappingGlobalValueChains_web_usb.pdf

Structure and length of value chains

Kirill Muradov

Click to access IO-Workshop-2017_Muradov_abstract.pdf

Click to access IO-Workshop-2017_Muradov_ppt.pdf

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3054155

Production Staging: Measurement and Facts

Thibault Fally

August 2012

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.717.7092&rep=rep1&type=pdf

TRACING VALUE-ADDED AND DOUBLE COUNTING IN GROSS EXPORTS

Robert Koopman

Zhi Wang

Shang-Jin Wei

November 2012

GIVE CREDIT WHERE CREDIT IS DUE: TRACING VALUE ADDED IN GLOBAL PRODUCTION CHAINS

Robert Koopman

William Powers

Zhi Wang

Shang-Jin Wei

September 2010

Click to access NBER%20working%20paper_1.pdf

Measuring the Upstreamness of Production and Trade Flows

By Pol Antràs, Davin Chor, Thibault Fally, and Russell Hillberry

2012

Click to access acfh_published.pdf

Using Average Propagation Lengths to Identify Production Chains in the Andalusian Economy

https://idus.us.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11441/17372/file_1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Production Chains in an Interregional Framework: Identification by Means of Average Propagation Lengths

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0160017607305366

Vertical Integration and Input Flows

Enghin Atalay

Ali Hortaçsu

Chad Syverson

2013

Click to access verticalownership.pdf

The Rise of Vertical Specialization Trade

Benjamin Bridgman

January 2010

Click to access the_rise_of_vertical_specialization_trade_bridgman_benjamin.pdf

THE NATURE AND GROWTH OF VERTICAL SPECIALIZATION IN WORLD TRADE

David Hummels

Jun Ishii

Kei-Mu Yi*

March 1999

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.475.3874&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Accounting for Intermediates: Production Sharing and Trade in Value Added

Robert C. Johnson

Guillermo Noguera

First Draft: July 2008

This Draft: June 2009

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.211.9707&rep=rep1&type=pdf

First Draft: July 2008

This Draft: May 2011

Click to access PAPER_4_Johnson_Noguera.pdf

FRAGMENTATION AND TRADE IN VALUE ADDED OVER FOUR DECADES

Robert C. Johnson

Guillermo Noguera

June 2012

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.679.6227&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Can Vertical Specialization Explain The Growth of World Trade

Kei-Mu Yi

1999

CAN MULTI-STAGE PRODUCTION EXPLAIN THE HOME BIAS IN TRADE?

Kei-Mu Yi

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

June 2008

This revision: November 2008

Global Value Chains: New Evidence for North Africa

D. Del Prete, G. Giovannetti, E. Marvasi

2016

Slicing Up Global Value Chains

Marcel Timmera Abdul Erumbana Bart Losa

Robert Stehrerb Gaaitzen de Vriesa

Presentation at International Conference on Global Value Chains and

Structural Adjustments,

Tsinghua University, June 25, 2013

Click to access session4_timmer.pdf

On the Geography of Global Value Chains

Pol Antràs

Alonso de Gortari

May 24, 2017

Click to access gvc_ag_latest_draft.pdf

Counting Borders in Global Value Chains

Posted: 12 Jul 2016

Last revised: 29 Aug 2016

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2808130

Determinants of country positioning in global value chains

Kirill Muradov

May 2017

Click to access 2932_20170627121_Muradov2017_countrypositioninGVC_1.1.pdf

THE CONSTRUCTION OF WORLD INPUT–OUTPUT TABLES IN THE WIOD PROJECT

ERIK DIETZENBACHERa*, BART LOSa, ROBERT STEHRERb, MARCEL TIMMERa and GAAITZEN DE VRIES

2013

Click to access WIOD%20construction.pdf

On the fragmentation of production in the us

Thibault Fally

July 2011

A New Measurement for International Fragmentation of the Production Process: An International Input-Output Approach

Inomata, Satoshi

http://www.ide.go.jp/English/Publish/Download/Dp/175.html

Output Upstreamness and Input Downstreamness of Industries/Countries in World Production

Date Written: July 9, 2015

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2700845

Input-Output Calculus of International Trade

Kirill Muradov

Date Written: June 1, 2015

Posted: 9 Sep 2015 Last revised: 5 Oct 2015

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2643098

Made in the World?

Date Written: September 2015

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2658562

The Average Propagation Length Conflicting Macro, Intra-industry, and Interindustry Conclusions

Accounting Relations in Bilateral Value Added Trade

Robert Stehrer

May 2013

Click to access accounting-relations-in-bilateral-value-added-trade-dlp-3021.pdf

Whither Panama? Constructing a Consistent and Balanced World SUT System including International Trade and Transport Margins

Measuring Smile Curves in Global Value Chains

Ming YE, Bo MENG , and Shang-jin WEI

August 2015

http://www.ide.go.jp/English/Publish/Download/Dp/530.html

FOLLOW THE VALUE ADDED: BILATERAL GROSS EXPORT ACCOUNTING

by Alessandro Borin and Michele Mancini

2015