Transcendental Self in Kant and Shankara

Source: Advaita Vedanta/Wikipedia

Three states of consciousness and Turiya

Advaita posits three states of consciousness, namely waking (jagrat), dreaming (svapna), deep sleep (suṣupti), which are empirically experienced by human beings,[125][126] and correspond to the Three Bodies Doctrine:[127]

- The first state is the waking state, in which we are aware of our daily world.[128] This is the gross body.

- The second state is the dreaming mind. This is the subtle body.[128]

- The third state is the state of deep sleep. This is the causal body.[128]

Advaita also posits “the fourth,” Turiya, which some describe as pure consciousness, the background that underlies and transcends these three common states of consciousness.[web 7][web 8] Turiya is the state of liberation, where states Advaita school, one experiences the infinite (ananta) and non-different (advaita/abheda), that is free from the dualistic experience, the state in which ajativada, non-origination, is apprehended.[129] According to Candradhara Sarma, Turiya state is where the foundational Self is realized, it is measureless, neither cause nor effect, all pervading, without suffering, blissful, changeless, self-luminous,[note 7] real, immanent in all things and transcendent.[130] Those who have experienced the Turiya stage of self-consciousness have reached the pure awareness of their own non-dual Self as one with everyone and everything, for them the knowledge, the knower, the known becomes one, they are the Jivanmukta.[131][132][133][134][135]

Advaita traces the foundation of this ontological theory in more ancient Sanskrit texts.[136] For example, chapters 8.7 through 8.12 of Chandogya Upanishad discuss the “four states of consciousness” as awake, dream-filled sleep, deep sleep, and beyond deep sleep.[136][137] One of the earliest mentions of Turiya, in the Hindu scriptures, occurs in verse 5.14.3 of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad.[note 25] The idea is also discussed in other early Upanishads.[138]

Key Terms

- Advait Vedanta

- Sankara

- Shankara

- Immanuel Kant

- Samkara

- German Idealism

- Transcendental Idealism

- Phenomenology

- Absolute Consciousness

- Phenomenal Consciousness

- Idealism vs Realism

- Maya

- Illusionism

- Appearance

- Reality

- Four States of Consciousness

- Turiya

- Jivanmukta

- Brahman Satyam, Jagat Mithya

- Maha Vakyas of Vedas

Kant and Shankara

08 SAMKARA AND KANT (Apr 1960)

VISHWANATH PRASAD VARMA

1. INTRODUCTION

Both Samkara and Kant were supreme thinkers who have played an almost revolutionary role in the philosophical history of India and Europe respectively. Samkara (788-820) was a great poet, a prince among dialecticians, a peripatetic teacher of Vedanta and a great system-builder. He tried to establish the foundations of Vedanta on the bases of the Upanishadic metaphysics. His philosophical constructions are characterized by logical subtlety, speculative fearlessness and a deep and profound concern for spiritual reality. Kant (1724-1804) was a great mathematician, a conservative social and political philosopher and the founder of the matchless majestic idealistic philosophy of Germany.1 An acute and analytical thinker, a man of tremendous learning, Kant lived a very simple life. While Kant’s eminence is confined to the realms of philosophy and political thought, Samkara’s position is far greater in the religious history of India.2 Samkara is hailed not only as a philosopher but a great religious leader who appeared as the spokesman of the old social and religious traditions against the devastating challenges of the Buddhist subjectivists and nihilists.

The bases of Samkara’s system are derived from the old tradition of idealistic wisdom recorded chiefly in the principal Upanishads although like all creative thinkers Samkara does add to them the fund of his own intuitional experiences and reflections. He flourished at the end of the eighth and the beginning of the ninth century A.D. when there was slender development of the physical sciences in the country. Hence Samkara’s system is logical, poetic and metaphysical but it has no roots in the physical sciences. The foundations of the Vedantic ideas regarding the origin and nature of the five physical elements and human physiology are largely intuitional and speculative and have no concrete experimental data behind them.

Kant, on the other hand was a far greater expert in science. His researches in cosmogony embodied in the famous nebular hypothesis although refuted by a later body of scientific knowledge show the cast of his intellectual temper. Kant appreciated the keen significance of scientific advancements. He wanted to make philosophy follow the road of science. The secret of the success of science is its methodology. Science is based on the acceptance of synthetic a priori judgments and they impart to it universality. The scientific advancements of the seventeenth century impressed Kant. He believed that the knowledge of mathematics and physics has the element of necessity and universality which are the dominant characteristics of objectivity. Kant differentiated the synthetic constructive character of mathematical propositions from the formal and analytical character of logical propositions. But these judgments can be applied only in the realm of the phenomenal and sensuous. Hence there can be no dogmatic assertions about the transcendent reality if metaphysics is to follow the methodology of the natural sciences. Kant is emphatic in his statement that the categories of the understanding do not apply to the Unconditioned. The unconditioned or the totality of conditions is for Kant an Ideal of Reason.3On this point the mystical tradition of the Vedanta which posits a sharp separation between the province of conceptual reason and the super-sensuous mystical immediacy of intuition would agree with him. According to Kant, speculative metaphysics transcending the bounds of the phenomenal sensuous concrete realm of experience is liable to the fallacies of the transcendental dialectic.

Although in his later writings he made concessions to the religious tradition, the scientific spirit is far more present in Kant than in Samkara, though it must be acknowledged that the great difference in their times—almost nine hundred years, is responsible for it.

Both Samkara and Kant were idealists. But while Samkara was a spiritual monistic idealist, Kant was an ethical idealist. The supreme brahman, beyond all subjects and objects is the sole real. Hence Samkara has been regarded as a ‘rigorous monist’. Samkara cannot be called an absolute idealist because in his system there is no dialectical derivation of the realms of the subject and the object from the supreme idea. Instead, the utter absolute spiritual real or brahman is intuited in mystical experiences and from that standpoint there is nothing real besides the brahman. Samkara is a transcendental idealist because the supreme brahman transcends the categories of predication by human thought but remains the fundamental real.

Kant, on the other hand, is both a transcendental idealist as well as an ethical idealist. Kant’s transcendental or logical idealism consists in the view that the phenomenal world of objects which is the only realm which has the characteristic of cognisability is an ideal construction framed by the application of the forms of intuition and the categories of the understanding to the sense-data. Sometimes the transcendental idealism of Kant is also called phenomenal idealism; Kant is also an idealist in the sense that he attributes primacy to moral values. He refutes, however, two types of idealism—the problematical idealism of Descartes and the dogmatical idealism of Berkeley.4 Kant recognizes the multiplicity of things-in-themselves although he denies the possibility of their knowledge. It is said by absolute idealists that the recognition of the things-in-themselves in the Kantian system is a relic of the Cartesian dualism of mind and matter. From the monistic standpoint while Samkara accepts the sole truth of the nirguna brahman, Kant recognizes, as if the perceived phenomenal multiplicity is the re-furnished garb of the multiple things-in-themselves. Thus theoretically speaking, the spiritual monistic idealism of Samkara is more satisfying than the objective idealism of Kant. Both Samkara and Kant remain critics of subjectivism. Samkara refutes the subjectivism of the Yogacara school of Buddhists. In refuting the standpoint of the Buddhist subjectivists, Samkara makes concessions to empirical inductive realism based on the universal concensus in fields of common perception of the same objects. He frankly states that the dominant activities in the mundane sphere would be impossible. Kant refutes the subjectivism of Berkeley.

2. METAPHYSICS

(a) Possibility and Nature of Knowledge

Samkara flourished at a time when the philosophical world was dominated by the Buddhists. The concept of Sunya as popularized by the Buddhist nihilists was a counterpoise to any fresh philosophic endeavour. In a way it amounted to the assertion of the futility of all epistemological constructions because nothing conclusive could be predicated either about the processes of knowledge or about the conclusions. Sunyavada implied the worthlessness of all categories of predication. Samkara took up this challenge. Following the traditions of Yajnavalkya and Uddalaka, Samkara once more asserted the possibility of knowledge. He recognized the limitations of the instruments of cognition but in spite of this awareness he gave, credence to the validity of a set of theoretical generalizations. Hume’s scepticism was an indirect challenge to all philosophical attempts at the construction of a cosmology and a philosophy of life. Kant recognized the necessity of using the process of self-scrutiny to the instruments of cognition. Kant is an exponent of the critical methodology which probes into a searching investigation of the potencies of reason. It gives transcendental knowledge ‘which does not relate so much to objects of knowledge, as to our mode of knowing them, in so far as knowledge is possible a priori’. If according to Samkara the inadequacies of empirical knowledge are to be traced to the blinding tantalizing potencies of maya or the indescribable (anirvachaniya) cosmic ignorance, Kant refers to the inadequate powers of the human instruments of knowledge in explaining these inadequacies. But in spite of the critical application of reason to the bases and limitations of reason, Kant rendered a great service to philosophy by stressing the necessity of a scientifically-oriented metaphysics, a task which, however, remains an aspiration rather than a realization. Kantian metaphysics, however, landed in phenomenalism and agnosticism because according to him the things-in-themselves remain permanently unknown and there can be no knowledge of the non-sensuous supersensible entities. Hence metaphysics as a science of the ultimate primordial reals is impossible. Metaphysics in the Kantian sense is mainly reduced to epistemological scrutiny. If the human reason attempts to overstep its province and aims to apply to regulative ideas of the reason—soul, world and God to experiential continuum the result is paralogism, antinomies and dogmatic assertions. The limitation of metaphysical enquiries to the realm of the sensuous is indicative of the influence of contemporary science on Kant.

One of the essential ingredients in the apercus of idealistic philosophy is the distinction between different levels of knowledge. This epistemological gradation is an analogue to the ontological gradation. If there is a distinction between the supreme supersensuous real being and the external surface phenomenal manifestations then the knowledge or apprehension of them must be obtained by different organs and instruments. Samkara accepts a fundamental distinction between the paramarthika truth—intuited by a transcendent supreme knowledge and the vyavaharika satta or the empirical layer of phenomena. The latter is comprehended by the commonplace media of sensuous apprehension. This distinction has its roots in the Upanishadic differentiation between tarka, vijnana or medha, that is, empirical understanding and prajnaor nidhidhyasana or supreme integral insight. In the Tripitakas we find Buddha making a similar distinction between the apprehension of the average man—the prithagjana and the transcendent vision of the sarnyak sambuddha. In the school of Nagarjuna there is a distinction between the samvriti satya and the paramartha satya. According to Samkara, the supreme transcendent indeterminate Brahman appears as a differentiated incongruous manifold under the clouding veil of the indescribable cosmic Maya. Kant did not accept the reality of a super-rational vision or intuition. He engages in a more thorough investigation of the nature of reason than Samkara. He makes a distinction between illusory knowledge and empirical knowledge. He accepts that the things-in-themselves are unknowable. Kant, however, holds that the things-in-themselves are somehow the significant factor in the generation of our experience although their own nature remains unrevealed in our experiences.

Samkara believed in the reality of a non-sensuous super-phenomenal immediate apprehension of the supreme real—anubhava-vasanatvat brahmavijnanasyat.5 He is a mystic and he accepts the possibility of a metaphysics based on the esoteric realizations of the old seers and sages. The critical philosophy of Kant, on the other hand, accepts that the regulative Ideas of Reason’ are methodological devices. There is no sense-experience corresponding to them. While Kant is emphatic in his assertion that sensibility is the sole giver of the content of experiences, Samkara in the perennial tradition of mystic spiritualism believes in the veracity of non-sensuous modes of immediate yogic realization. According to the Vedantic and Yogic tradition there is a direct luminous’ awareness of the supreme real if there is a regeneration of the human heart and if the necessary disciplines in the shape of intellectual purification have been undergone. The bodhi or the prajna is the culminating point of a sustained process of philosophical concentration and absorption. The mystical tradition is far stronger in the case of Samkara. Kant refuses to accept that there can be any non-sensuous intuitional immediacy.6 Thus while Samkara is a believer in mystical metaphysics, Kant is a metaphysical agnostic accepting the permanent non-cognisability of the things-in-themselves. Both Samkara and Kant are agreed that the postulational conceptual categories of human deliberation are non-applicable to the supreme real but while Kant does not point to any super-rational faculty, Samkara accepts the testimony of inspired mystical vision and revelation. While Kant keeps himself confined to the legitimate province of philosophy, Samkara makes a transition to the realms of theology and mysticism. While Kant defined philosophy as the criticism of cognition and thus was mainly preoccupied with the transcendental foundations of the possibility of knowledge, Samkara adhering to the long line of Indian spiritual tradition sang hymns in praise of the supernal self.

A familiar element in any idealistic theory is the notion of superposition or illusion. If the brahman is the sole spiritual real, there must be some intellectual device to explain the appearance of this phenomenal world. Samkara adopts the concept of adhyasa for it. Adhyasa implies the imposition of the categories of the non-ego upon the ego and vice versa. In other words adhyasa flourishes on a confusion between the attributes of the subject and the object. The appearance of the world is a case of adhyasa which is founded upon the peculiar conjunction of truth and error. This concept is similar to the Kantian theory of transcendental illusion according to which phenomenal predications are applied to the cognising subject which is supposed to be another to the realm of external objects. The illusion consists in the antithetical juxtaposition of the thinking subject and the external things outside of it. Kant, however, would ascribe greater reality to the phenomenal world than Samkara. He does not regard the phenomenal world as illusory or as a shadow. He only indicates that it implies something of a transcendent order to justify its existence. The mystic-ascetic Samkara harps on the non-being of the world in endless refrain.

(b) Theory of God

According to Samkara, from the human standpoint, God is the highest reality and is the subject of adoration. Though the conception of God is accounted for on a dualistic hypothesis, God, basically is the same as the supreme real, the Brahman or the Sachchidananda. The Saguna Brahman or the personal Lord or Isvara is the same fundamental reality as the Brahman or the absolute. But Kant does not acknowledge this distinction between the impersonal philosophical absolute and the personal God. Samkara was a theist from the practical standpoint although from the standpoint of abstract philosophical-mystical contemplation he recognized the sole reality of a superior absolute. He does recognize that the adoration of God is a necessity so long as the dualistic standpoint relevant to the phenomenal world is there. In establishing the reality of God Samkara took recourse to the cosmological argument. The Upanishads refer to the cosmological argument and thereby point to the reality of a creative supreme agency—tajjalaniti. The Yoga system and Leibnitz accept the teleological argument for theism. There is the implicit acceptance of the teleological argument also in the Vedanta philosophy. But the Vedanta as interpreted by Samkara puts the basic emphasis on the cosmological argument. Samkara refers to the statement of the Taittiriya Upanishad—Yato imani bhutani jayante and says that this refers to the Saguna Brahman. Kant pointed out the difficulties and insufficient character of the ontological, the cosmological, and the physico-theological arguments.7 His famous ridicule of the Ontological or Cartesian argument for the existence of Supreme Being contained in his saying that there is a lot of difference between the idea of hundred dollars (or marks) in the mind and hundred dollars in your pocket shows his humourous mode of argumentation.8 Instead of these arguments, Kant sponsored the moral argument which accepts God as a regulative Idea of Reason and as a postulate of the moral life. Thus if the cosmological argument is sponsored by Samkara, Kant is an advocate of the moral argument. In Kant’s philosophy of theism there is a dual standpoint. Sometimes his rationalism and scientific training make him conceive of God, as in the Critique of Pure Reason as a methodological device or a regulative notion of reason that helps in conceiving objects of our thought as integral elements in a systematic whole. According to Kant the Ideal of Reason is the final presupposition of limited experiences. He stated that the three Ideas of Reason—World, Soul and God, do not constitute the entities corresponding to them. They are unobjectified regulative principles. Hegel is critical of the Kantian view regarding the supra-experiential character of the Ideal of Reason and he identifies it with philosophical conceptualization. In the Critique of Practical Reason, Kant justified the existence of God on moral grounds. Although God’s existence cannot be logically demonstrated on the theoretical foundations of pure reason God is a necessity of the moral life. A second view of God is also quite implicit in the writings of Kant. Sometimes Kant gives indirect hints of his belief in the Christian conception of God as Saviour.9

I am more inspired by the Samkarite conception of God because I think that it attributes greater importance to the being of God. Kant’s conception of God as a regulative idea of reason or as a mere postulate of the moral consciousness reduces the exaltedness and sublimity that attach to God when he is conceived as a being or a spiritual ultimate real. The conception of God as a regulative Idea of Reason deprives him of all substantiality.

(c) The Atman and the Transcendental Ego

Samkara believed in the reality of the atman which is the inmost essence and real spiritual being of man. The reality of the atman is established on the evidence of immediate apprehension. No sentient being ever experiences as if he were “not”. Everyone feels and thinks that he is. This universally felt and cognized self-certainty, according to Samkara, is the basis of the belief in the reality of the self. Samkara accepts the identity of the innermost being of the individual with the brahman. Samkara teaches the identity of the cosmic brahman and the individual inmost self. Each individual self is the supreme brahman fully. But separate distinctions and multiple particularisations have been caused by maya which imposes the upadhi on the brahman. But the individualization brought about by maya is only a phenomenal feature. Essentially the jiva or the individual self is the same reality as the brahman. He refuses to believe in the eternal continuous monadic entities or personal distinct individual selves. There are no separate real selves. They are only apparent particularizations of the supreme real. Thus the atman represents for Samkara, the supreme subject which can never be objectified. The acceptance of the reality of the self was aimed as a counterpoise to the Buddhist concept of anatman.The atman cannot be sensuously perceived and intellectually cognized. According to Samkara ‘the witness self illumines consciousness, but never itself is in consciousness.’ It is a nonobjective non-experiential super-subject. It is the referent in all acts of experience though by itself it transcends the acts of experience.

Hume had, like the Buddhists, denied the substantialist conception of the Self. Kant took up this challenge. He accepted the distinction between perception and apperception made by Leibnitz and recognized the reality of a transcendental unity of apperception as the necessary organizing faculty behind all transformations of the sense-manifold into items of knowledge through the mediating agency of the categories of understanding. Kant says: ‘The I think must accompany all my representations, for otherwise something would be represented in me which could not be thought; in other words, the representation would either be impossible, or at least be, in relation to me, nothing. That representation which can be given previously to all thought, is called intuition. All the diversity or manifold concept of intuition, has, therefore, a necessary relation to the I think, in the subject in which this diversity is found. But this representation, Ithink, is an act of spontaneity; that is to say, it cannot be regarded as belonging to mere sensibility. I call it pure apperception, in order to distinguish it from empirical; or primitive apperception, because it is a self-consciousness which, while it gives birth to the representation Ithink, must necessarily be capable of accompanying all our representations. It is in all acts of consciousness one and the same, and unaccompanied by it, no representation can exist for me. The unity of this apperception I call the transcendental unity of self-consciousness, in order to indicate the possibility of a priori cognition arising from it. For the manifold representations which are given in an intuition would not all of them be my representations, if they did not all belong to one self-consciousness, that is, as my representations (even although I am not conscious of them as such), they must conform to the condition under which alone they can exist altogether in a common self-consciousness, because otherwise they would not all without exception belong to me.’10 This transcendental unity of apperception is the synthetic power of self-consciousness. It accounts for the unity in experiences which are in themselves diverse and multisided. It provides the ‘affinity of phenomenal forms.’ The subjective and objective dichotomies in the empirical plane of consciousness are conceived on the basis of this fundamental self. This transcendental unity of apperception is never, however, the simple monadic immortal substance. This noumenal or transcendental ego, or the knowing subject, according to Kant, is the fundamental basis of empirical consciousness but is never itself a factor in or participant in empirical consciousness. It is the condition and the possibility of the awareness of multiple phenomena. But it cannot be objectified. Thus Kant made the transcendental unity purely formal and hence could not make it the supreme derivative principle for all experience. This cannot be known through the categories of the understanding which pertain to the field of scientific experience. The transcendental ego is the pre-condition of empirical knowledge and itself is never the subject of knowledge. Kant says: ‘What I must pre-suppose in order to know an object I cannot know as an object.’

Both Samkara and Kant accept an organizing foundational basis for the systematization of bits of experiences into knowledge. But while the atman, according to Samkara is a real entity and the subject of immediate non-sensuous apprehension, the Kantian transcendental unity of apperception is a synthesizing construction or even a non experienceable logical abstraction and is, at best, parallel to the Vedantic concept of the buddhi but never to that of the atman.11 While the atman is an unchangeable real, Kant demolished the Cartesian notion of the substantialist character of the soul-substance. In his Paralogism of Rational Psychology Kant maintained only the logical, non-substantialistic, dynamic unitive character of mental life and operations. On the other hand in the Samkarite conception the substantialistic independent character of the atman is of uppermost significance. While the atman is the highest being whose essence is bliss and consciousness and which is intuited in the highest stages of Samadhi, the transcendental unity of apperception is a mere logical coordinating possibility and a contentless pure form.

3. ETHICAL TRANSCENDENCE VERSUS ETHICAL ABSOLUTISM

Samkara does acknowledge the necessity of mental and moral purification or sadhana chatustaya for the preparation of a life of philosophical gnosis. But he does not care much for the social implications of his propositions. In his philosophic reveries over-anxious to establish the separate dimensions of ethics and philosophical gnosis—jnana, he relegates ethics to the subordinate realm of mundane phenomena and illusion.

The system of Kant ascribes a more exalted and dignified place to ethical experience. Moral commands are unconditioned, universal and imperative. They have a categorical binding character. According to Kant virtue consists in ceaseless moral endeavours towards perfection. The rationality of human nature demands the realization of the summum bonum whose attainment implies holiness or the perfect congruity between the psychic structure of man and the moral law. There is no point in time when the goal may be said to have been attained. The exaltedness of the moral man lies in the constancy of the moral exercise which imparts to him ever-growing realization. Kant makes the moral consciousness almost akin to religious consciousness.12 The voice of conscience becomes for him the command of God almost. The immense importance of ethical experience in Kantian philosophy proceeds from two sources, (a) It ascribes to man moral primacy and regards him as a citizen of the kingdom of ends. Thus the belief in the universality of the moral law ultimately leads to the conception of a spiritual commonwealth, (b) To register the validity of the belief in the commensurability of moral acts and their meritorious rewards Kant postulates the existence of a God whose reality is the guarantee of the final redemption of virtue. Like Plato and Aristotle, Kant accepted the supreme worth of virtue but to the classical conception of virtue he also added the utilitarian conception of happiness which in its origins is a secularized form of the Christian concept of felicity and beatitude. Kant accepted the reality of the universal instinct in man which seeks to apportion happiness as a reward of virtue. If virtue is to be fully realized and if the proportionate amount of happiness is to be attained, there must be the immortality of the soul. A cessation of life would imply the end of the virtuous life once begun. Hence Kant accepted the reality of a God who dispenses happiness in accordance with virtue.

In spite of the inner consistency of his system, from the standpoint of a democratic, social and political philosophy Samkara’s system is less satisfying than that of Kant. While Kant is all the time anxious to view moral laws with an attitude of dignity, awe and reverence, the ascetic Samkara sings hymns in praise only of knowledge and views moral piety with some kind of indifference. Samkara has thus rendered a positive disservice to the cause of ethical life.

4. CONCEPT OF FREEDOM

According to Samkara the universe is the vivarta or only the apparent transformation of brahman, hence there is no real scope for any genuine exercise of freedom by the human self which in its actions in the world is impelled by the force of maya. But in the spirit of the Upanishads Samkara agrees that whosoever knows the brahman and cognizes his inmost seif to be that same brahman, he attains freedom or yathakamachara.According to Samkara the brahman is supreme freedom and absolute non-difference and its creative abundance is unhindered by any competing eternal ideas. Kant also accepted that in the phenomenal realm of the universal operation of natural forces there could be no question of freedom. He however maintained that ‘man is free’ and thus in place of phenomenal determination stood for the creative autonomy of man. In place of phenomenal rigidity he stood for spontaneity. Kant bases the freedom of man on moral foundations. Freedom is the demand of a moral life. Kant pointed out that it is not possible for theoretical reason to emancipate itself from the limitations consequent upon the dualistic juxtaposition of the subject and the object. In the realm of the practical reason the self can transcend these barriers and enjoy the creative spontaneity of a free self-expressive life. The theoretical reason is chained to the sensuous objective phenomenal world which obeys the necessary laws, but the practical mind solely determined by the moral law which is its own prescription is emancipated from necessity and in its free autonomous orientation to an absolute teleology is a citizen of a superior kingdom. Thus if Samkara bases the freedom of man on spiritual knowledge, Kant bases human freedom on the concept of moral autonomy and spontaneity.

There is a tendency in the interpreters of the Vedantic thought to find the final roots of all modern values like freedom in the concept of the brahman.13 But I regard it as unfortunate. From the standpoint of the development of human personality and social growth it does not serve any purpose to compose poems of eulogy about the transcendence and supreme luminosity of the brahman. Kant has a far greater appreciation of the significance and ramifications of freedom. Samkara flourishing in an era of monarchical despotism and feudalism did not have as keen an appreciation of freedom as Kant who flourished at an epoch when Lutheranism had proclaimed the sanctity of individual conseience and capitalism was proclaiming the absence of restraint on competition in the economic field. While to Samkara everything attains its final salvation in getting sunk into a mighty indeterminate brahman, Kant’s modernism is revealed in his greater appreciation of the ethics and sociology of freedom.

5. CONCLUSION

The monistic trend is far stronger in Samkara than in Kant. At the epistemological level the latter points the duality between sense-data and the intuitional forms and categories of the understanding. At the ontological level there is the duality between the things-in-themselves and the phenomenal world. Kant posits three regulative ideas of reason and does not derive them from a higher or superior idea. It is true, however that the theme of unity was not absent from his mind. There are hints of the concept of unity in the Prolegomena. But the unitary implications of the Kantian system were only drawn out in the later phases of the German idealistic philosophy. Samskara’s conclusion is partly in consonance with the later developments of German idealism in Schelling and Hegel. The indeterminate featureless brahman, however, reminds me more of the One of Parmenides than of the identity in difference which is the cardinal element in Hegelian idealism. Modern Indian interpreters of Samkara try to bring out the superiority of the latter to Kant by stating that the former could independently arrive at the conclusions which became explicit only in the later post-Kantian idealism.14 But it should be pointed out that the concept of Samkara’s brahman has its foundation in the intuitional grasp of the poets and seers, although it is, later on, substantiated by a vast framework of logical arguments. On the other hand, the scientific positive background of the Kantian philosophy should be stressed. I do not consider the mere arrival at the concept of unity to be of great philosophical significance. The eminence of a philosophical system lies in its capacity to synthesize the knowledge derived from the natural sciences and the social sciences as well as from literature and other disciplines, Kant’s philosophy attempts to harmonize a far greater range of knowledge than Samkara’s.

There was a time when I had profound reverence for Samkara on nationalistic and emotional grounds. Now I believe in a synthetic comprehensive approach to problems of philosophy. It is not possible to revive the scholastic and dogmatic methodology of Samkara. Neither is there any basis to give credence to the theory of three disparate sectors of the mind—cognitional, practical and emotional-aesthetic. Both Samkara and Kant have failed to utilize thoroughly the possible contributions of the social and historical sciences for the elaboration of their metaphysical structure, though Kant should be given the credit for having written three books in the field of political philosophy. In modem Indian thought the influence of Samkara is in one sense marked because all idealistic scholars pay homage to him but almost all of them have bid good bye to the Samkarite concept of maya and even the faithful are too busy reading the ideas of phenomenalism in his thought. There had been a revival of Kantianism and Natrop, Cohen, Vorlander, Cassirer, Adler, Eduard Benstein and others tried to re-buttress some of the ideas of the German philosopher. But neo-Kantianism also is a passing phenomenon. On logical grounds there are vital difficulties in the acceptance of the systems of both Samkara and Kant. On rational grounds Samkara’s eschatology cannot be defended, neither is it possible to work out a defence of space and time as subjective forms of intuition. But nevertheless Samkara and Kant stand as vindications of the superiority of the quest into cosmology and axiology. They have permanent and epoch-making place in the history of philosophy. Even for a construction of metaphysical system in the present, their inconsistencies and contradictions can provide suggestions. Although ī find both Samkara and Kant unsatisfying, I have always been impressed by the Kantian concept of moral autonomy. In the days of blighting totalitarianism the Kantian theory of the autonomy, spontaneity and dignity of man is a great theme in the history of human civilization. It may not be possible to support the exact structure of concrete values for which Samkara stood but still he has taught the abnegation of the superficial concern with external glamour and sensual attractions. Hence although the epistemological and ontological bases of the Samkarite and Kantian philosophies be not palatable in our world, both of them are undaunted spokesmen of the superiority of a dignified free philosophic life.

References:

1 A modem German existentialist philosopher like Karl Jasper hails Kant as ‘the philosopher par excellence’ and ‘the prototype of a philosopher’ (den philosophen schlechthin). The Philosophy of Karl Jasper, Edited by P. A. Schilpp, (New York, Todor Publishing Company, 1957), pp. 381, 424.

2 C. N. Krishnaswami Aiyar, Life And Times of Samkara, pp. 8-9; D. N. Pal, Samkara The Sublime. See also the Samkara-Digvijaya.

3 Sometimes it is said that Kant upheld the view that the Unconditioned is amenable to the grasp of intellectual intuition.

4 Kant, Critique of Pure Reason. E. T. by J. M. D. Mikeljohn (New York, 1900), p. 147.’

5 Experience is the culmination of divine gnosis.

6 There seems to be no corroboration for S. Radhakrishnan’s view: ‘Kant spoke of an intellectual intuition to indicate the mode of consciousness by which a knowledge of things in themselves might be obtained in a non-logical way.’ See S. Radhakrishnan, Indian Philosophy, (Indian Edition), Vol. II. pp. 512-513. The Kantian term intuition, does however, comprehend both sensibility and intellectual intuition.

7 Fant, Critique of Pure Reason, op. cit., pp. 331-337, ‘Of the Impossibility of an Ontological Proof of the Existence of God’; pp. 337-347, ‘Of the Impossibility of a Cosmological Proof of the Existence of God’; pp. 347-353, ‘Of the Impossibility of a Physics-Theological Proof’.

8 Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, op. cit.,pp. 335-6.

9 Clement Weble, Kant’s Philosophy of Religion,p. 158 says that Kant criticized Judaism as misanthropic, Mohammedanism as proud, Hinduism as pusillanimous and the spurious Christianity of Pietism, hoping to acquire merit by self-contempt as servile. Kant, however, was influenced by the teachings of Protestantism. For Kant’s conception of the Christian conception of Grace, see Edward Caird, The Critical Philosophy of Kant,Vol. II, p. 545.

10 I. Kant, Critique of Pure Reasoti, E. T. by ĩ. M. D. Mikelejohn, Renaissance Edition, (New York, The Colonial Press, 1900), pp. 76-77.

11 When the transcendental ego is compared to the atman, then the empirical ego is regarded as the analogue of the Vedantic concept of manas and buddhi. The Kantian concept of the synthetic unity of apperception in which there is the recognition of the centrality of consciousness was universalized by Hegel into a pan-logical self-conscious absolute.

12 In his Religion Within the Bounds of Pure Reason, (1793) Kant tries to reduce religion to morality. He states that there is a necessary transition from morality to religion because the highest good or summum bonum is a necessary ideal of the reason.

13 Mahendranath Sircar, Hindu Mysticism London, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubuer & Co., 1934), p. 3, says: ‘He (Kant) did not see that the soul can be spontaneously creative and at the same time transcendent. Its creativeness is apparent, transcendence is its being’ I regard it as a confusion to identify creative freedom with an ocean of transcendence.

14 P. T. Raju, Thought emit Reality (London, George Allen & Unwin, 1937); Ibid., Idealistic Thought of India (London, George Allen & Unwin. 1953); H. JM. Bhattacharya, The Principles of Philosophy (University of Calcutta. 1948); P. T. Raiu ‘Kant’s Idea of Reason and the Brahman of Samkara’, Proceedings of the Eighth Indian Philosophical Congress (Calcutta. Town Art Press, 1933), pp. 290-291.

My Related Posts

You can search for these posts using Search Posts feature in the right sidebar.

- Ether in Kant and Akasa in Prasastapada: Philosophy in comparative perspective

- God, Space and Nature

- Purush – The Cosmic Man

- The Transcendental Self

- Ervin Laszlo and the Akashic Field

- Five Types of Systems Philosophy

- Hua Yan Buddhism : Reflecting Mirrors of Reality

- Indira’s Pearls: Apollonian Gasket, Circle and Sphere Packing

- Process Physics, Process Philosophy

- Networks and Boundaries

- Networks and Hierarchies

- Myth of Invariance: Sound, Music, and Recurrent Events and Structures

- Sounds True: Speech, Language, and Communication

- Consciousness of Cosmos: A Fractal, Recursive, Holographic Universe

- Fractal and Multifractal Structures in Cosmology

- Cantor Sets, Sierpinski Carpets, Menger Sponges

- Fractal Geometry and Hindu Temple Architecture

- Rituals | Recursion | Mantras | Meaning : Language and Recursion

- From Systems to Complex Systems

- Hierarchy Theory in Biology, Ecology and Evolution

- Theories of the Self

- Theories of Consciousness

- What is Yogacara Buddhism (Consciousness Only School)?

- Self and Other: Subjectivity and Intersubjectivity

- A Calculus for Self Reference, Autopoiesis, and Indications

- Individual Self, Relational Self, and Collective Self

- Semiotic Self and Dialogic Self

- Drama Therapy: Self in Performance

- Narrative Psychology: Language, Meaning, and Self

- Mind, Consciousness, and Quantum Entanglement

- Geometry of Consciousness

- The Harmonic Origins of the World

- From Individual to Collective Intentionality

- Lifeworld, System, and Intersubjectivity: Jurgen Habermas’ Communication Theory of Society

- Intersubjectivity in Buddhism

- Meditations on Emptiness and Fullness

- Charles Sanders Peirce’s Continuum

- What and Why of Virtue Ethics ?

- The Aesthetics of Charles Sanders Peirce

- Individual, Relational, and Collective Reflexivity

- Semiotics and Systems

- Dialogs and Dialectics

- Phenomenological Sociology

- Phenomenology and Symbolic Interactionism

- Aesthetics and Ethics

- Maha Vakyas: Great Aphorisms in Vedanta

- On Synchronicity

- Truth, Beauty, and Goodness

- Indra’s Net: On Interconnectedness

- On Holons and Holarchy

- Levels of Human Psychological Development in Integral Spiral Dynamics

- The Great Chain of Being

- Cyber-Semiotics: Why Information is not enough

- Integral Philosophy of the Rg Veda: Four Dimensional Man

- Systems View of Life: A Synthesis by Fritjof Capra

- Society as Communication: Social Systems Theory of Niklas Luhmann

- Truth, Beauty, and Goodness: Integral Theory of Ken Wilber

Key Sources of Research

The Relevance of Kant’s Transcendental Idealism to Advaita Vedanta, Part I

The Relevance of Kant’s Transcendental Idealism to Advaita Vedanta, Part II

The Relevance of Kant’s Transcendental Idealism to Advaita Vedanta, Part III

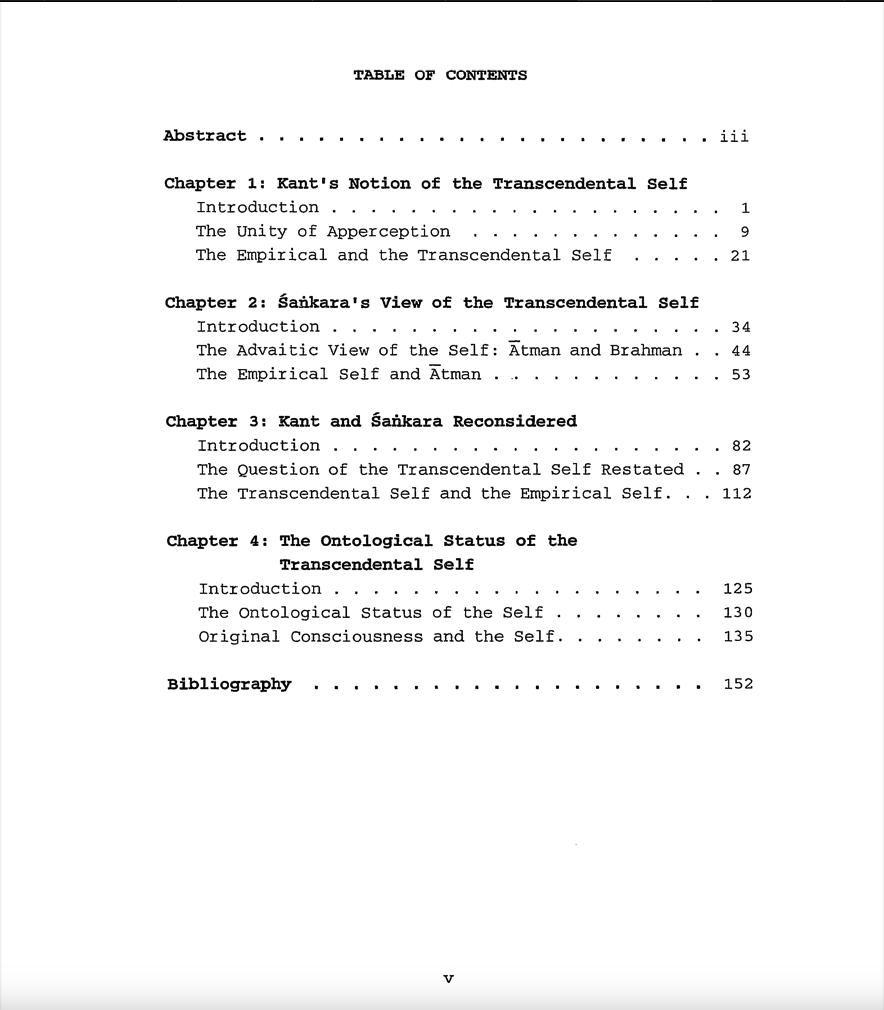

The Ontological Status of the Transcendental Self: A Comparative Study of Kant and Sankara.

Sewnath, Ramon (2005).

Thesis (Ph. D.)–University of Hawaii at Manoa, 1996

Peter Lang.

https://philpapers.org/rec/SEWTOS

SANKARĀCHĀRYA AND KANTIAN NOTION OF CONSCIOUSNESS

Manas Sahu

In this paper, my objective is to show how Sankarāchārya’s concept of reality is different from the Kantian notion of reality, despite many similarities between them. Cartesian skepticism of universal doubt is a challenge for the Kantian notion of reality; however, it can’t be applied to Sankarāchārya’s concept of reality because of the acceptance of different paradigm to explain the reality and his non-representationalistic approach towards the reality. The attack on representationalism can’t be applicable to Sankarāchārya’s philosophy.

https://www.academia.edu/41473169/SANKARĀCHĀRYA_AND_KANTIAN_NOTION_OF_CONSCIOUSNESS

An Advaitic View of Kantian Philosophy

SWAMI SHANTIDHARMANANDA SARASWATI

PUBLISHER: KALPAZ PUBLICATIONS

LANGUAGE: ENGLISH

EDITION: 2005

ISBN: 817835321

https://www.exoticindiaart.com/book/details/advaitic-view-of-kantian-philosophy-uan743

Space and time a comparative study of Kant and Sankara

http://hdl.handle.net/10603/69509

Name of the Researcher Goswami, Geeta

Name of the Guide Chakravarty, D K

Completed Year 31/12/1995

Name of the Department Department of Philosophy

Name of the University Gauhati University

https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/handle/10603/69509

Consciousness Indian and Western Perspectives (Sankara, Kant and Hegel, Lyotard, Derrida and Habermas)

Hardcover – January 1, 2008

by Raghwendra Pratap Singh (Author)

Atlantic (January 1, 2008)

Language : English

Hardcover : 560 pages

ISBN-10 : 8126909773

ISBN-13 : 978-8126909773

Śaṅkara

SEP

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/shankara

“Atman is Brahman” – How Absolute Idealism originated in Indian Philosophy

http://critique-of-pure-interest.blogspot.com/2017/06/atman-is-brahman-origin-of-absolute.html

Chapter 3. The History of Religious Consciousness: Kant, Hegel, Descartes and Shankaracharya

The Development of Religious Consciousness

by Swami Krishnananda

https://www.swami-krishnananda.org/conscious/consc_3.html

The Vedanta of Shankara

IGNCA

The Real and the Constructed.

The Philosophy of Shankara

M A Buch

The Absolute of Advaita and the Spirit of Hegel: Situating Vedānta on the Horizons of British Idealisms.

Barua, A.

J. Indian Counc. Philos. Res. 34, 1–17 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40961-016-0076-4

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40961-016-0076-4

08 SAMKARA AND KANT (Apr 1960)

VISHWANATH PRASAD VARMA

https://vk.rkmm.org/s/vkm/m/vedanta-kesari-1960/a/08-samkara-and-kant-apr-1960

Vedanta or the Science of Reality

NAB767

AUTHOR: K.A. KRISHNASWAMY IYER

PUBLISHER: ADHYATMA PRAKASHAN KARYALAYA, BANGALORE

EDITION: 2018

PAGES: 540

https://www.exoticindiaart.com/book/details/vedanta-or-science-of-reality-nab767/#

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.22640

The System of Sankara

Dr. Will Durant

https://www.kamakoti.org/souv/2-6.html

Kant and Śankara on Freedom.

Stroud, Scott R. (2003).

South Pacific Journal of Philosophy and Culture 7.

Advaita Vedanta

Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Advaita_Vedanta

The Absolute of Advaita and the Spirit of Hegel: Situating Vedānta on the Horizons of British Idealisms

26 October 2016

The Absolute of Advaita and the Spirit of Hegel: Situating Vedānta on the Horizons of British Idealisms

Abstract

Purpose

A significant volume of philosophical literature produced by Indian academic philosophers in the first half of the twentieth century can be placed under the rubric of ‘Śaṁkara and X’, where X is Hegel, or a German or a British philosopher who had commented on, elaborated or critiqued the Hegelian system. We will explore in this essay the philosophical significance of Hegel-influenced systems as an intellectual conduit for these Indo-European conceptual encounters, and highlight how for some Indian philosophers the British variations on Hegelian systems were both a point of entry into debates over ‘idealism’ and ‘realism’ in contemporary European philosophy and an occasion for defending Advaita against the charge of propounding a doctrine of world illusionism.

Methodology

Our study of the philosophical enquiries of A.C. Mukerji, P.T. Raju, and S.N.L. Shrivastava indicates that they developed distinctive styles of engaging with Hegelian idealisms as they reconfigured certain aspects of the classical Advaita of Śaṁkara through contemporary vocabulary.

Result and Conclusion

These appropriations of Hegelian idioms can be placed under three overlapping styles: (a) Mukerji was partly involved in locating Advaita in an intermediate conceptual space between, on the one hand, Kantian agnosticism and, on the other hand, Hegelian absolutism; (b) Raju and Shrivastava presented Advaitic thought as the fulfilment of certain insights of Hegel and F.H. Bradley; and (c) the interrogations of Hegel’s ‘idealism’ provided several Indian academic philosophers with a hermeneutic opportunity to revisit the vexed question of whether the ‘idealism’ of Śaṁkara reduces the phenomenal world, structured by māyā, to a bundle of ideas.

Similar content being viewed by others

The theme of the emergence of certain forms of Hinduisms through various types of east–west dialogical interactions has been extensively studied in recent decades. From around 1900 onwards, some Hindu thinkers began to assimilate and critically interrogate a diverse range of European ‘imaginations’ of India, such as Christian missionary critiques of Hindu socio-religious universes, Orientalist projections of golden Vedic antiquities and enquiries into Indo-European linguistic morphologies, and utilitarian denunciations of the ‘primitivism’ of Hindu cultural systems. A topic that has been relatively underexplored in these intellectual transmissions and exchanges is the engagement of a range of Indian academic philosophers in the first half of the last century with a variety of Hegel-inspired philosophical systems. A significant volume of philosophical literature from this period can be placed under the rubric of ‘Śaṁkara and X’, where X is Hegel, or a German or a British philosopher who had commented on, elaborated or critiqued the Hegelian system. We will explore in this essay the philosophical significance of Hegel-influenced systems as an intellectual conduit for these Indo-European conceptual encounters, and highlight how for some Indian philosophers the British variations on Hegelian systems were both a point of entry into debates over ‘idealism’ and ‘realism’ in contemporary European philosophy and an occasion for defending Advaita against the charge of propounding a doctrine of world illusionism.

The reception in Indian academic philosophical milieus of Hegelian thought, often mediated through British philosophers such as T.H. Green (1836–1882), E. Caird (1835–1908), and F.H. Bradley (1846–1924), was not uniform. While H. Haldar (University of Calcutta) was primarily a Hegelian thinker, who only occasionally employed Vedantic terminology to elucidate certain aspects of Hegel’s system, A.C. Mukerji (University of Allahabad), P.T. Raju (Andhra University and the University of Rajasthan), S.N.L. Shrivastava (Vikrama University, Ujjain), and others directly drew from the perspectives of Advaita to critique specific themes in Hegelian thought. For Mukerji, Raju, Shrivastava, and others, Hegelian idealisms provided the common conceptual currency with which they could critically intervene in European philosophical disputes and also present Advaita Vedānta to European audiences. Consequently, the term ‘Absolute’ routinely appears in their texts, and, in fact, as S. Deshpande has noted, ‘the singular question that occupied these philosophers in the early part of the twentieth century was as follows: “What is the nature of the Absolute?”’ (Deshpande 2015: 19). As we will see, Mukerji, Raju, and Shrivastava developed distinctive styles of engaging with Hegelian idealisms as they reconfigured certain aspects of the classical Advaita of Śaṁkara through contemporary vocabulary. These appropriations of Hegelian idioms can be placed under three overlapping styles: (a) Mukerji was partly involved in locating Advaita in an intermediate conceptual space between, on the one hand, Kantian agnosticism and, on the other hand, Hegelian absolutism; (b) Raju and Shrivastava presented Advaitic thought as the fulfilment of certain insights of Hegel and Bradley; and (c) the interrogations of Hegel’s ‘idealism’ provided several Indian academic philosophers with a hermeneutic opportunity to revisit the vexed question of whether the ‘idealism’ of Śaṁkara reduces the phenomenal world, structured by māyā, to a bundle of ideas. Our exploration of three central texts, Mukerji’s The Nature of Self (1943), Raju’s Thought and reality: Hegelianism and Advaita(1937), and Shrivastava’s Śaṁkara and Bradley: A Comparative and Critical Study (1968), will indicate that these philosophical currents formed a dense network stretched across three vertices: Hegel himself; the receptions and the reconfigurations of Hegel in a wide range of British idealists, from Green to Caird to Bradley; and the Indian philosophical interrogations, from the perspectives of modernized Advaita, of both Hegel himself and the British idealists who incorporated aspects of Hegelianism into their own metaphysical systems. While ‘British Idealism’, which emerged from around 1870, was not a singular movement but a group of somewhat divergent philosophical standpoints, D. Boucher and A. Vincent highlight a few shared themes. First, according to British idealism, there are no isolated entities or processes, and everything has to be understood in terms of their relationships within an internally differentiated whole. Second, the world is dependent on mind, not in the sense that it owes its very existence to mind but that it derives its intelligibility from mind. The claim is not that, for instance, a table ceases to exist once it is taken away from an observer, but that carpenters, scientists, and artists could see three different types of tables, where these differences are dependent on mind (Boucher and Vincent 2012: 39). These themes were critically received by the British idealists from the philosophical projects of German idealists who sought to respond to the critical idealism of Kant, variously by searching for an unconditional first principle of knowledge (Fichte), a philosophy of identity (Schelling), the absolute knowing which overcomes all subject–object dualisms (Hegel), and so on (Dudley 2007). Mukerji, Raju, Shrivastava, and others, as we will see, critically appropriated specific aspects of the ‘holism’ of the Hegelian Absolute, and also the post-Kantian critique of Berkeleyean idealism, as they reformulated, for the purpose of their philosophical conversations with Hegelianisms, some of the metaphysical themes of Advaita Vedānta. The Absolute of Advaita, it turns out, is not to be understood as the ‘subjective idealism’ of Berkeley, but not quite as the ‘absolute idealism’ of Hegel either, though it is conceptually much nearer the latter standpoint than the former.

Advaita Between Kant and Hegel

Mukerji’s The Nature of Self (henceforth, NS) is a careful and systematic exploration of certain philosophical positions in British idealisms regarding the self. He sketches three broad patterns of British philosophical responses to Kant. First, though Kant had critiqued the basic assumption of Hume’s empiricism, namely, that the epistemic subject first begins with a bundle of atomic sensations and then proceeds to unite them through psychological bonds of association, his transcendental idealism has not been properly appreciated in some strands of British philosophy. Various forms of contemporary realisms, pragmatisms, and pluralisms operate with the pre-Kantian view that things are self-existing distinct entities before they enter into relations with one another. While some philosophers have indeed rejected the basic thesis of British empiricists such as Locke, Berkeley, and Hume—that the world is composed of self-existing, metaphysically independent and isolated entities which are only subsequently related to one another through conceptual abstractions—they have arrived at two somewhat divergent conclusions. First, some have moved towards Kant’s agnosticism regarding the noumenon, and view the self as a bare that which remains completely unknowable. Second, others have elaborated Hegelian understandings of self-consciousness in terms of the self’s developing awareness of itself through its awareness of objects, thereby reducing the self, according to Mukerji, to the status of an empirical entity. At this critical stage of the argument, Mukerji presents Śaṁkara’s Advaita as a via media between these extremes in post-Kantian idealisms: on the other hand, the Absolute of Advaita (unlike the Kantian noumenon) is not utterly unknowable, for it is the self-revealing consciousness which is the ever-present background illumination in all empirical knowledge, but, on the other hand, the Absolute of Advaita (unlike the Hegelian organic whole) is a pure undifferentiated unity and not the self-consciousness structured by identity-in-difference of various British ‘neo-Hegelian’ idealisms. Mukerji’s philosophical project, then, is not a nativist-styled return to Śaṁkara, but a creative intervention, from modernized Advaita perspectives, in post-Kantian metaphysical and epistemological debates about the nature of consciousness.

Mukerji begins by noting that the problem of the self is structured by a paradox: while every object implies a self that knows that object, this statement would suggest that there must also be a knower that knows the self (NS, 5). According to Mukerji, the question ‘Who knows the knower?’ signals a key debate across a range of contemporary British philosophers, who have, however, missed the point that the self is not only not an empirical object but also not a psychological subject. The notion that the self is essentially unknowable through empirical modes is found in various Upaniṣadic texts and subsequently in Śaṁkara’s understanding of the self. This doctrine has recently emerged in Kant’s critical philosophy, where his critique of rational psychology for mistakenly extending the categories of thought to the transcendental ego is, according to Mukerji, reminiscent of the teachings of the Upaniṣads and Śaṁkara (NS, 24). Philosophers should avoid the confusion, labelled transcendental illusion by Kant and adhyāsa by Śaṁkara, of mistaking the pure ego with the objects of knowledge, for by overlooking the distinctions between the innermost subject and the empirical objects, there arises various mistaken theories such as epiphenomenalism and behaviourism (NS, 26).

Mukerji notes that two methods have been developed in recent British philosophy to resolve the egocentric paradox, namely, the experimental or inductive method, and the logical or transcendental method. The former is employed by psychologists such as J.B. Watson who seek to replace the vocabulary of consciousness with that of physiological processes. These attempts to remove the pure ego from an analysis of knowledge commit the fallacy of the ‘decentralization of the self’, which involves the misidentification of the real self with objective entities and states, which are in fact spurious egos. The fundamental problem that theories produced through this method have to face is that of an infinite regress: when a subject S knows objects O, each with specific properties, S itself cannot have these properties, for it would then become another object and would require S* by which it can be known (NS, 9–12). The basic error lies in the forgetfulness on part of the subject S that S itself stands in a unique relation to the objects which cannot be excavated through an empirical analysis. For instance, when knowledge is reduced to a set of physiological and mental processes, it is forgotten that these processes are intelligible to S only if the transcendental conditions of S’s relation to them are not reducible to the relations between objects. One such transcendental condition for the conceivability of an object is that it is a self-consistent unity. Therefore, when S knows an object A and another object B, the interobjective relations that obtain between A and B are completely distinct from the ‘relation’ of A and B individually with S. The inductive method is not capable of uncovering these transcendental conditions of possible experience, because it is precisely these conditions, discoverable only through a reflective analysis of the nature of knowledge, that make the application of the method possible (NS, 15). On the other hand, the Kantian transcendental method correctly emphasizes that the ‘logical implicates of experience’ such as space, time, and causality cannot be known in the same way that specific empirical objects are known. The post-Kantian developers of this method argue that all objective entities, such as tables and trees, as well as the universal conditions of objects of experience, such as space and time, exist for the self which is in this sense ‘the centre of the universe’. Mukerji notes that this method has ‘staunch advocates not only in England where Hegelianism has come to establish itself as a permanent philosophical tendency, but it is accepted as final also by many accomplished thinkers of contemporary Italy and India …’ (NS, 17).

However, while British idealists such as Green and Caird have correctly accepted the transcendental approach to the ego, they are engaged in a ‘logical see-saw’ in which they have alternately emphasized one of the following points, both of which they have inherited from Kant: the self as the transcendental presupposition of empirical objects, and the self as unknowable. Green has highlighted the distinction between the pure ego and empirical objects and denied that the pure ego is knowable, while Caird has emphasized the knowability of the pure ego and almost removed its distinction from empirical objects (NS, 70). Mukerji has in mind statements of Green such as the following: ‘That there is such a consciousness is implied in the existence of the world; but what it is we only know through its so far acting in us as to enable us, however partially and interruptedly, to have knowledge of a world or an intelligent experience’ (NS, 74). According to Mukerji’s reading, if Green veers, in this manner, towards a deep agnosticism about the self, Caird, on the other hand, mistakenly introduces empirical categories into the self. Caird argues that the self constitutes itself by opposing itself as its object, and by overcoming this very opposition, such that the self is a concrete unity of identity-in-difference. Unity and difference should be seen as inseparably connected in self-consciousness, through which the self knows itself and all its objects: ‘the self exists as one self only as it opposes itself, as object, to itself, as subject, and immediately denies and transcends that opposition. Only because it is such a concrete unity, which has in itself a resolved contradiction, can the intelligence cope with all the manifoldness and division of the mighty universe …’ (Caird 2002[1883]: 116). Responding to Caird’s notion of the self as an ‘organic unity’, Mukerji allows that unity-in-difference may be the most universal form to which every object of experience conforms; however, this universality does not show that the true subject itself is a unity-in-difference, for the subject is the logical presupposition of all categories, including the category of ‘unity’ which cannot be applied to the subject (NS, 18–19). Therefore, he criticizes Caird for viewing the self as the correlative of the not-self, arguing that on this account the self is another empirical object, and not the real self which is the presupposition of all objects (NS, 21). Mukerji’s Kantian point is that since a ‘category’ is a principle of interpretation that is employed to objects of experience, the self cannot itself be a category, even the highest category, since every category implies an ultimate unity (NS, 98–99).

The point of this subtle discussion of the complexities of British idealisms emerges gradually: Mukerji seeks to situate Advaita in a conceptual space somewhere between the systems of Caird and Green. On the one hand, because Caird views self-consciousness as a unity that is mediated through its consciousness of objects, he effectively views the self as an empirical object (NS, 90). Noting Caird’s view that only with the ‘return’ of the self to itself or the reduplication of the self in the judgment ‘I am I’, that the ‘ego, strictly speaking, comes into existence’ (Caird 1889: 403), Mukerji argues that this developmental account of the self, which progresses from consciousness to self-consciousness, presupposes the categories of space and time which are the transcendental conditions of any entity that undergoes a processive change. Therefore, Caird’s developmental self cannot be the true subject, which is the very source of the categories and cannot be an object which is comprehended by the categories (NS, 88). Mukerji is more sympathetic to Green’s engagements with Kant, noting that both Green and Śaṁkara view consciousness as a reality which has none of the characteristics that belong to knowable objects (viṣaya) (NS, 144). He argues that Śaṁkara’s argument that every perceptual judgement involves two principles, namely an unchanging spiritual unity (cit) and a stream of transient cognitions (vṛtti–pravāha) of the mind (antaḥkaraṇa), is analogous to Kant’s distinction, later elaborated by Green, between the transcendental unity of apperception and the successive states of knowledge. Mukerji comments: ‘And what must be eminently interesting for a modern philosopher is the similarity of Green’s analysis with that of Sankara’ (NS, 175). However, while both Śaṁkara and Green highlight the point that the self is the logical presupposition of experience and hence cannot be placed under the categories, there is a fundamental divergence in their conceptual systems regarding the question of knowledge of the self. While Green, following Kant, exhibits a ‘drift to agnosticism’ and regards the noumenal self as completely unknowable, the Advaita standpoint is that self-revealing consciousness (svayaṃprakāśa), which is both eminently real and yet not an object, is present in all empirical consciousness (NS, 129–130). According to Mukerji, the basic error of Kant, and of Green in his Kantian moments, is to view reality, on the one hand, and the phenomenal world, on the other hand, as congruent, and to conclude from this equivalence that the noumenal self, because it is unknowable, is merely an imaginary point. According to Advaita, however, reality is more expansive than Kant’s phenomenal world, so that the pure consciousness of Advaita, though indescribable, is not a completely inconceivable x, but rather ‘the indispensable support of all objects and of all relations among the objects’ (NS, 342). Therefore, the Advaita of Śaṁkara gives us, according to Mukerji, a conceptual pathway that avoids the errors of Caird and Green: on the one hand, the Absolute of Advaita cannot be characterized in terms of any empirical categories which are relational, but, on the other hand, it is not a Kantian thing-in-itself which is entirely unknown. Sankara avoids the ‘opposite fallacies’ of viewing the self as an empirical object (which, according to Mukerji, is effectively Caird’s response to Kant) and as a pure nothing (which is the ‘drift’ of Green), for while Sankara emphasizes that the conditions under which objects are known cannot be applied to the knower, he also asserts that ‘what is thus beyond the conditions of the knowable objects is our very self. The self in this sense is said to be beyond the known and above the unknown’ (NS, 270). Thus, the Advaitic self is not unknown and unknowable in the same sense as the Kantian noumenon. The self is said to be self-revealing, for everyday experience presupposes a ‘self-experience’ which is the condition of empirical knowledge. However, this ‘self-experience’ is not the experience of the self as an object, rather it is a non-objectifying immediate experience which, in an Advaita analogy, is like light which does not stand in need of an external light for is own illumination. The ‘entire tenor and drift’ of the Upaniṣads is that Brahman, far from being a transcendental principle that is unknown or otherwise accessible only to mystics, is ever present in the ‘self-experience’ of everyday life (NS, 378). The self of Advaita should not be viewed as a transcendental Principle, along the lines of a Platonic archetype, but rather as the immanent presupposition of all experience. Therefore, the unity of consciousness, for Śaṁkara, is not an abstract unknown but is ‘real in a certain sense’ (NS, 341).

The crucial phrase here is ‘in a certain sense’, for if Mukerji seeks to situate Śaṁkara between Green and Caird, this is also because he presents Advaita as an intermediate path through the systems of Kant and Hegel. While the Absolute of Advaita is the most foundational reality, and not a mere conceptual limitation such as the Kantian noumenon, it is not a relational whole such as the Hegelian Absolute. On the one hand, Mukerji draws extensive parallels between Śaṁkara’s views on the self and Kantian statements about the noumenal self. Mukerji argues that Kant’s affirmation of the transcendental unity of apperception can be put in Śaṁkara’s terms as follows: the conscious self is the presupposition (grāhikā) of the fleeting events of knowledge (NS, 218). Pointing out that Śaṁkara restricted categories such as generic unity, specific difference, action, quality, and relation to empirical objects, Mukerji comments that it may be ‘remarked without running the risk of being accused of overzeal that Sankara was essentially expressing the same truth that inspired Kant’s doctrine at a later age’ (NS, 157). The most significant of Śaṁkara’s conclusions, namely, that the ‘foundational character’ of unvarying consciousness is the presupposition of our experience of objects is also a theme that is shared by the contemporary ‘idealistic school’ which states that the self provides the a priori conditions of the determination of the objects of experience. Mukerji states that the ‘development of post-Kantian idealism bears eloquent testimony to the vitality of the Advaita position and the former may in this respect be regarded as an elaborate exposition and ramification of the latter’ (NS, 119). However, as we have noted, Mukerji’s basic objection to the Kantian system is the postulation of the noumenon, and he argues that this thing-in-itself has been ‘rightly rejected’ by idealists such as Fichte and Bradley. While Kant concludes with an agnosticism about the self, for Śaṁkara the Absolute is the pre-established ground (svayaṃsiddha) of all relational thought (NS, 308–309). Śaṁkara does claim that the Absolute is beyond all speech and thought, but he also affirms that Brahman is not a mere nothing (abhāva) (Brahma–sūtra–bhāṣya III.2.22; NS, 311). On the other hand, Mukerji’s rejection of the Kantian noumenon does not amount to a full-fledged acceptance of the Hegelian system. He argues that while the Advaita tradition agrees with Hegel that distinctions presuppose an underlying unity, it rejects Hegel’s understanding of the infinite. Whereas for Hegel, true infinity is not opposed to its other but includes it, so that the highest category of reality is that of unity-in-difference, Advaita responds that unity-in-difference itself is a category that applies to objects but not to the Absolute which is the very presupposition of these objects (NS, 350). Mukerji therefore offers a critique of post-Kantian idealisms for transforming Kant’s transcendental subject into a universal Spirit by viewing the Kantian logical unity as a determinate object, which is a unity manifested in differences. The error lies, according to Mukerji, in viewing the noumenal subject not simply as a limiting concept but as a positive, though trans-phenomenal, thing or object of thought (NS, 104–105). These post-Kantian idealists view subject and object as correlative terms, so that an object of thought should be properly understood in terms neither of identity nor of difference, but of identity-in-difference, which is a unity of differents. At the same time, the subject is regarded as a higher-order reality, because this correlativity of subject and object is a correlativity for the subject. This line of argument ‘gradually leads to the conclusion that the world is the self-manifestation of a spiritual principle which is a universal that differentiates itself and yet is one with itself in its particularity’ (Mukerji 1936: 448). Mukerji rejects the basic premise of this argument, namely, that subject and object are correlative, noting that the true subject cannot be placed under any empirical categories that apply to objects, since it is the logical presupposition of empirical experience. However, because of the influence of Hegelianism, thinkers from different countries mistakenly continue to reject the notion of the self as pure consciousness. They wrongly assume that the self comes into existence through the I-consciousness which contrasts itself with consciousness of objects; rather, it is because the self exists as a synthetic principle that the I-consciousness can emerge with pure consciousness as its transcendental presupposition (NS, 333). Therefore, while there is a ‘strong tendency’ on the part of some Indian philosophers such as Haldar to minimize the distinctions between Advaita and Hegelian absolutism, there is in fact a ‘deep chasm’ between the two: Hegelian idealism is based on the mediated unity of the concrete universal, whereas Advaita is grounded in a pure immediacy which is not an organic unity of distinct individuals (NS, 277–79).

Advaita as the Fulfilment of Hegel and Bradley

Mukerji’s basic theme that Advaita rejects the Hegelian Absolute as a spiritual unity-in-difference which expresses itself in parts also appears in Raju and Shrivastava, who expressly present the Absolute of Advaita as the most consistent resolution of the conceptual puzzles involved in ‘relating’ the one and the many. By drawing on various classical Advaitins such as Śrī Harṣa, they argue that the Hegelian Absolute, which they read as a relational whole of the eternal and the temporal, is logically contradictory—the Advaita of Śaṁkara, in contrast, cannot be placed under any categories of thought, including identity-in-difference which is a relational category. They highlight the point that Bradley places his Absolute above the operations of categorical thought: according to Bradley, relational experience is riddled with inner contradictions which can be resolved only in the ‘immediate experience’ of the supra-rational Absolute. Bradley’s Appearance and Reality contains various turns of phrase which, for his Indian Vedantic interlocutors, are reminiscent of the Advaita theme of māyā as the principle of the phenomenal world’s inexplicability, for instance, Bradley’s statement that ‘[t]he fact of appearance, and of the diversity of its particular spheres, we found was inexplicable. Why there are appearances, and why appearances of such various kinds, are questions not to be answered’ (Bradley 1893: 511). However, while Bradley’s Absolute approximates to the Absolute of Advaita in some respects, his Vedantic readers ultimately reject his system on the grounds that he retains the Hegelian error of regarding the Absolute as an organic whole of interrelated elements.

Raju argues in his Thought and reality: Hegelianism and Advaita (henceforth, TR) that while Hegelians struggle to explain the relation between the infinite and the finite, the proper response to this problem is that, strictly speaking, no such relation can be logically elaborated. If this relation is viewed as an identity-in-difference, this category is simply a restatement of the problem in different terms, for one would have to explain the relation itself between identity and difference (TR, 44). He discusses various Hegelian attempts to relate individuals to the organic whole of the Absolute and argues that they are unsuccessful in logically spelling out the relation between distinct substantial selves and the eternally perfect Absolute (TR, 58). The ‘relation’ of the finite and the infinite, the ‘crux of all monism’, has been most successfully addressed by Śaṁkara: while all finite selves are, sub specie aeternitatis, identical with Brahman, they are, sub specie temporis, characterized by multiplicity. If one self is liberated, māyā, which structures the phenomenal world, disappears only for it and not for others, so that in this sense each self has a distinct individuality. However, noumenally the self does not exist as a substantial identity, for it is one with Brahman, which is without a second. Therefore, we can move from Bradley to Śaṁkara with only a ‘few steps’: Bradley correctly notes that appearances, such as the finite self, are riddled with internal contradictions, and these must undergo a complete transmutation into the Absolute. However, Bradley continues to retain the appearances somehow in the Absolute, because he is not entirely willing to view the Absolute as totally beyond thought. Raju claims that ‘[h]ad Bradley given up his Hegelian bias, rejected the appearance as such as in no way forming part of reality, and thus saved the eternal perfection of the Absolute, he would have joined hands with Sankara’ (TR, 61).