Frames, Communication, and Public Policymaking

My previous post was on introducing frames, framing and reframing. I focused on use of frames in areas of

- Media

- Communication

- Sociology and Social Movements

- Political Science

- International Relations

Frames and Framing are used in two other areas

- Frame Effects in Decision Making /Kahneman and Tversky

- Frame Analysis in Public Policy Making / David Schon and Martin Rein

This post is focused on Frame Analysis as used in public policy making.

Frames and Frame Analysis

Source: From Policy “Frames” to “Framing”: Theorizing a More Dynamic, Political Approach.

The concept of frames or framing, especially cast as “frame analysis,” has an established history in public policy studies, building largely on the work of Donald Schön and Martin Rein. It is an important analytic “tool” for those seeking to understand, for instance, issues in the mismatch between administrators’ implementation of legislated policies and policy intent. Originally coined elsewhere (Bateson, 1955/1972a), the concept had, by the 1990s, been taken up in a wide range of academic disciplines. These included, in addition to public policy analysis (e.g., Rein, 1983a, 1983b; Rein & Schön, 1977; Schön, 1979/1993; Schön & Rein 1994, 1996), artificial intelligence and psychology (e.g., Minsky, 1975; Schank & Abelson, 1977; Tversky & Kahneman, 1981), linguistics (e.g., Fillmore, 1982; Lakoff, 1987; Tannen, 1979; see Cienki, 2007), social movement studies (e.g., Gamson, 1992; Morris & Mueller, 1992; Snow & Benford, 1988; Snow, Rochford, Worden, & Benford, 1986; for an overview, see Benford & Snow, 2000), communication studies (e.g., D’Angelo, 2002; de Vreese, 2012; Entman, 1993; for a critical overview, see Vliegenthart & van Zoonen, 2011), dispute resolution (e.g., Dewulf et al., 2009; Putnam & Holmer, 1992), and even music (Cone, 1968). Yet as the Rein–Schön policy analytic approach to framing is, today, less well known than its version in the social movement literature, public policy and administration scholars might be more likely to turn to the latter than the former in seeking to explain frame-related issues. Given what we see as the greater suitability of their approach for analyzing policy processes, we think the ideas they developed worth revisiting and extending in ways that enhance their applicability to dynamic, power-sensitive policy and administrative issues.

Although Schön also explored the subject in his own scholarship on metaphors (1979/1993) and reflective practice (e.g., 1983, 1987)—each of which might be understood, at least in part, as engaging aspects of framing—its policy applications are most fully elaborated in his collaborative work with Rein. Where Rein used “frame-reflective analysis” interchangeably with “value- critical analysis” (on this point, see Schmidt, 2006/2013), together they began focusing on frame analysis as “a methodology for problem setting” (Rein & Schön, 1977, p. 237). Later, they added its utility for investigating the possible resolution of policy controversies (Rein & Schön, 1986, 1993), and in particular those they saw as “stubborn” (Rein & Schön, 1991) or “intractable” (Rein & Schön, 1996; see also Rein, 1983a, 1983b; Schön, 1963/2001): prolonged debates on issues marked by uncertainties and ambiguities that were “highly resistant to resolution by appeal to evidence, research, or reasoned argument” (Schön & Rein, 1994, p. xi).1 Their collaboration ultimately led to the co-authored Frame Reflection (Schön & Rein, 1994).

Schön and Rein’s approach to frame analysis has been generative for many policy scholars across a range of topics, from waste management to immigrant integration, civil aviation to bovine TB (see, for example, Dudley, 1999; Grant, 2009; Hajer & Laws 2006; Hisschemöller & Hoppe, 1996; Kaufman & Smith, 1999; Laws & Rein, 2003; Rasmussen, 2011; Schmidt, 2006/2013; Scholten & Van Nispen, 2008; Sørensen, 2006; van Eeten, 2001; Yanow, 2009). Still, for all its utility, their approach warrants further development to realize its policy analytic potential in the context of intractable policy controversies, in particular with respect to the promise it holds out of a dynamic, process-oriented engagement that is politically nuanced and power-sensitive. In this context, it would be particularly suitable for understanding interactions not only in formal political arenas but also in governance networks (Koppenjan & Klijn, 2004) and in the more mundane encounters between street-level bureaucrats and their clients (Lipsky, 1980; Maynard-Moody & Musheno, 2003; Vinzant & Crothers, 1996). In extending their approach, we draw on various ideas we find in Schön’s earlier solo work (1963/2001, 1971), and we join Schön and Rein’s treatment of policy frame analysis with ideas deriving from category and narrative analyses, two related analytic modes.

To make the potential contributions of this policy analytic focus on framing clearer, we differentiate it from approaches that focus on frames. In our reading of these approaches, social movement theorizing chief among them, “frames” are often treated as objects people possess in their heads and develop for explicitly strategic purposes. By contrast, the policy analytic approach we engage here shifts the focus to “framing,” the interactive, intersubjective processes through which frames are constructed (cf. Weick, 1979).2 This distinction is more significant than mere differences between parts of speech: “frame” signifies a more definitional, static, and potentially taxonomizing approach to the subject; “framing” offers a more dynamic and, in our view, potentially politically aware engagement. Although the two treatments are not necessarily mutually exclusive,3 each brings different features of the processes conceptualized as frames/framing to light. To be sure, Schön and Rein’s work has aspects of both: Their case studies (e.g., of home- lessness; 1994) trace policy developments over time, listing policy programs adopted in specific cases whose names are the equivalent of different frames on the policy problem, and the policy settings of those cases introduce some elements of political processes. Our argument develops the political character of policy processes more fully, thereby enabling a policy-focused frame theorizing and analysis that flesh out the more dynamic and politically sensitive aspects of their work. This also enables us to address some of the issues raised by social movement and dispute resolution studies’ treatments of frames (e.g., Benford, 1997; Dewulf et al., 2009).

Knowing something of the conceptual history out of which frame analysis emerged clarifies what is at stake in these different approaches. We begin there and with Schön’s and Rein’s basic ideas before turning to the further development of a policy analytic approach.

Key Terms

- Frame Analysis

- Frame Reflection

- Frames

- Framing

- Reframing

- Media Frames

- Communication

- Policy making

- Action Learning

- Learning in Action

- Reflection in Action

- Organizational Learning

- Double Loop Learning

- Gregory Bateson

- Erving Goffman

- Chris Argyris

- Martin Rein

- Donald Schon

- Reflective Practitioner

- Interpretative Frames

- Cognitive Frames

- Interactional Frames

- Contextual Frames

- Sensemaking

- Sensegiving

- Priming

- Agenda-setting

- Persuasion

- Schemas

- Scripts.

- Levels of Analysis

- Micro, Meso, Macro

- Deep Frames

- Issue Defining Frames

- Surface Messages

- Frame Alignment

- Frame Consonance

- Frame Discordance

- Contested Frames

Categories of Frames: Policy Frames Codebook

Source: Identifying Media Frames and Frame Dynamics Within and Across Policy Issues

Our Policy Frames Codebook is intended to provide the best of both worlds: a general system for categorizing frames across policy issues designed so that it can also be specialized in issue-specific ways. The codebook contains 14 categories of frame “dimensions” (plus an “other” category) that are intended to be applicable to any policy issue (abortion, immigration, foreign aid, etc.) and in any communication context (news stories, Twitter, party manifestos, legislative debates, etc.). The dimensions are listed below.

- Economic frames: The costs, benefits, or monetary/financial implications of the issue (to an individual, family, community or to the economy as a whole).

- Capacity and resources frames: The lack of or availability of physical, geographical, spatial, human, and financial resources, or the capacity of existing systems and resources to implement or carry out policy goals.

- Morality frames: Any perspective—or policy objective or action (including proposed action)— that is compelled by religious doctrine or interpretation, duty, honor, righteousness or any other sense of ethics or social responsibility.

- Fairness and equality frames: Equality or inequality with which laws, punishment, rewards, and resources are applied or distributed among individuals or groups. Also the balance between the rights or interests of one individual or group compared to another individual or group.

- Constitutionality and jurisprudence frames: The constraints imposed on or freedoms granted to individuals, government, and corporations via the Constitution, Bill of Rights and other amendments, or judicial interpretation. This deals specifically with the authority of government to regulate, and the authority of individuals/corporations to act independently of government.

- Policy prescription and evaluation: Particular policies proposed for addressing an identified problem, and figuring out if certain policies will work, or if existing policies are effective.

- Law and order, crime and justice frames: Specific policies in practice and their enforcement, incentives, and implications. Includes stories about enforcement and interpretation of laws by individuals and law enforcement, breaking laws, loopholes, fines, sentencing and punishment. Increases or reductions in crime.

- Security and defense frames: Security, threats to security, and protection of one’s person, family, in-group, nation, etc. Generally an action or a call to action that can be taken to protect the welfare of a person, group, nation sometimes from a not yet manifested threat.

- Health and safety frames: Healthcare access and effectiveness, illness, disease, sanitation, obesity, mental health effects, prevention of or perpetuation of gun violence, infrastructure and building safety.

- Quality of life frames: The effects of a policy on individuals’ wealth, mobility, access to resources, happiness, social structures, ease of day-to-day routines, quality of community life, etc.

- Cultural identity frames: The social norms, trends, values and customs constituting culture(s), as they relate to a specific policy issue

- Public opinion frames: References to general social attitudes, polling and demographic information, as well as implied or actual consequences of diverging from or getting ahead of public opinion or polls.

- Political frames: Any political considerations surrounding an issue. Issue actions or efforts or stances that are political, such as partisan filibusters, lobbyist involvement, bipartisan efforts, deal-making and vote trading, appealing to one’s base, mentions of political maneuvering. Explicit statements that a policy issue is good or bad for a particular political party.

- External regulation and reputation frames: The United States’ external relations with another nation; the external relations of one state with another; or relations between groups. This includes trade agreements and outcomes, comparisons of policy outcomes or desired policy outcomes.

- Other frames: Any frames that do not fit into the above categories.

Researchers may choose to employ only these categories as listed here, or they could also nest issue-specific frames (or arguments) within each category. For example, in the case of capital punishment, the “innocence” frame would be a frame specific to that issue but categorized under the dimension of “fairness and equality.” In this way, scholars can apply the Policy Frames Codebook to new content analysis projects or take existing datasets that employed issue-specific frames and categorize those frames into the dimensions provided here.

We developed these categories through a mix of inductive and deductive methods. We began by brainstorming—amongst our team and several colleagues—categories that we imagined would cross- cut most, if not all, policy issues while also examining a random sampling of newspaper stories and blog posts to see which frames appeared and how we might categorize them. Then we tried applying our preliminary list of frame categories to a random sample of front-page newspaper stories covering a wide range of issues, and revised our categorization scheme accordingly. Next, we shopped our list around, sending it to additional colleagues and presenting it at an international conference (the 20th International Conference of Europeanists), again revising our schema based on this feedback. Finally, we did another round of test coding. Throughout this testing process, we developed and revised not only our list of categories but also a codebook that defines and gives examples for each category.

Framing: a Fractured Paradigm

Source: Putting Framing in Perspective: A Review of Framing and Frame Analysis across the Management and Organizational Literature

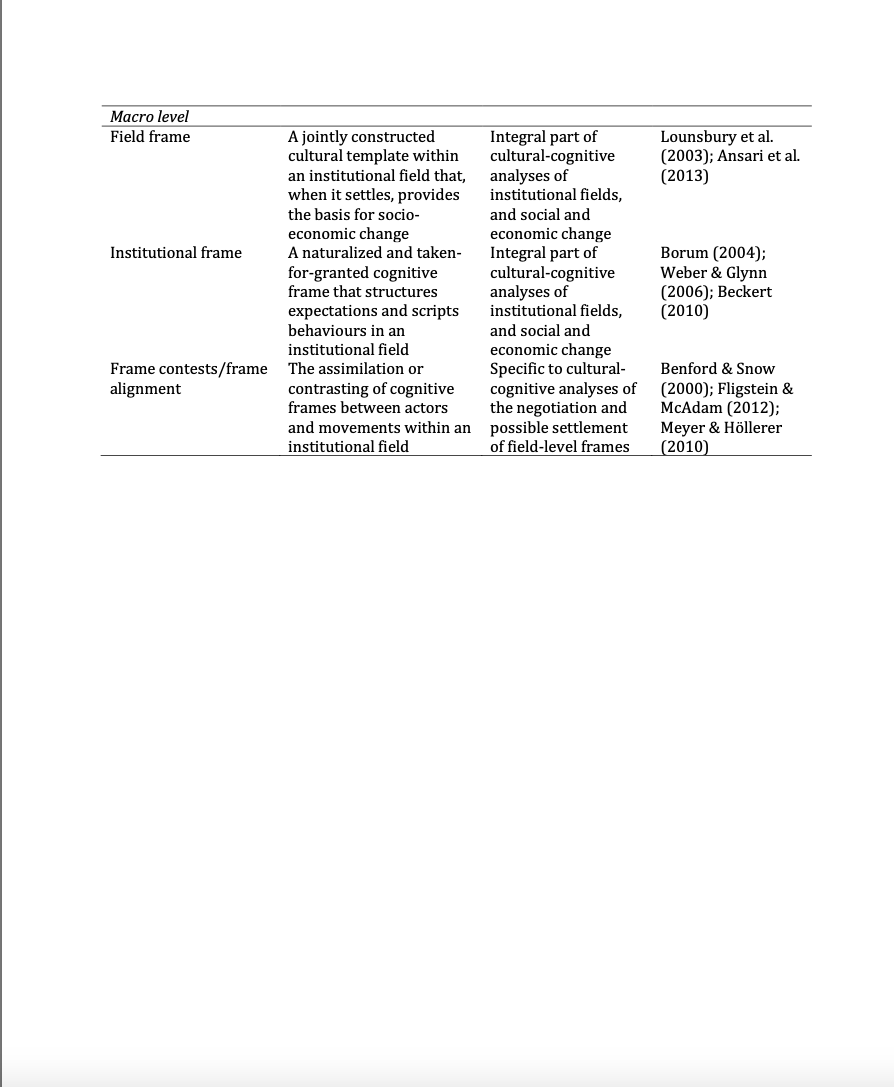

Framing and frames form an important cornerstone of many areas of management and organizational research – even if, at times, the interest in related constructs (such as schemas or categories) has seemingly had the upper hand. In one sense, our paper has been an attempt to take stock of the current literature while further advancing and invigorating research into the role of framing across the micro, meso and macro levels of analysis in management and organization studies. In part, this motivation has been driven by a recognition of the analytical strength and versatility of the construct, as evidenced by the various research streams that it has spawned within management, and indeed across the social sciences. At the same time, this vast influence across areas of research has perhaps also come at a price. It has led to a “fractured paradigm” (Entman, 1993), with researchers typically adopting a singular and more narrow focus on the construct at a particular level of analysis.

A general consequence of bracketing the broader construct in this way is that it has deflected attention away from processes of framing as meaning construction to a focus on frames as stable symbols or thoughts, with many studies setting out to “name” frames and explore how they prime certain thoughts and behaviours (e.g., Benford, 1997; Schneiberg & Clemens, 2006). The focus, in other words, is on the effects of cognitive frames, once these are established, in structuring expectations and cueing behavioural responses. This is useful for explaining how default frames may impinge on actors, and may script their behaviour, but does not account for how such frames of reference emerge in the first place. The bracketing of the construct may thus have blinded researchers to the active struggles and negotiations over meaning that take place before a frame might emerge, and before the meaning of an organized group or indeed an entire institutional field might contract around a frame.

We point in the paper to specific research opportunities and methods that enable further research to progress beyond “naming frames”, and explore framing as dynamic processes of meaning construction within and across groups and organizations. To a large extent, these opportunities will also involve research designs and methods that make stronger connections across levels of analysis, and consider the reciprocal influence between language, cognition, and culture. The methods that we have highlighted, ranging from interaction analysis to semantic-network analysis, are adept at this and allow for richer and more processual analyses of framing. Indeed, we hope that these methods will benefit researchers in realizing the highlighted opportunities and in advancing research on framing across a variety of organizational and institutional contexts.

Framing – Cognitive and Interactional

Source: Framing mechanisms: the interpretive policy entrepreneur’s toolbox

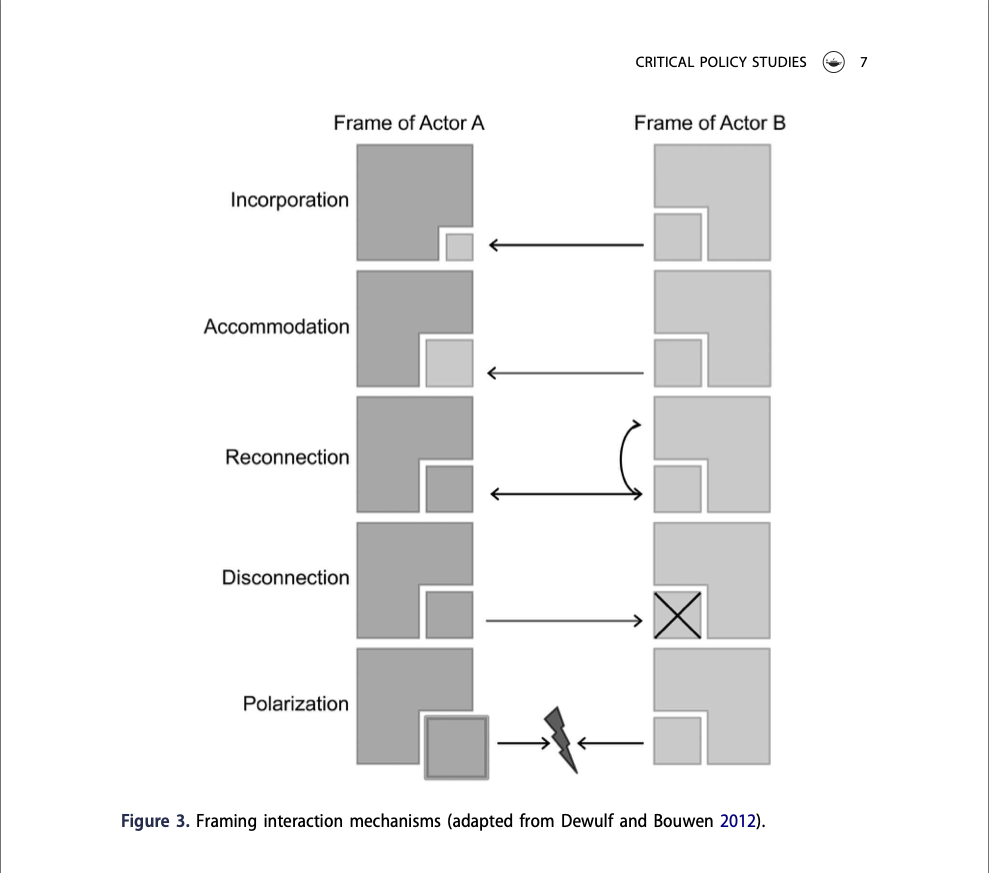

The framing literature is divided into two streams – a cognitive and an interactional type. Cognitive framing entails the individual understanding of a (policy) situation by assigning meaning to elements and binding them together in a coherent story (Scholten and Van Nispen 2008; Stone 2002; Van Hulst and Yanow 2014; Hawkins and Holden 2013). The interactional framing literature engages with the interactive effects of frames. Part of that literature focuses on the instrumental use of framing for ‘the rhetorical functions of persuasion, justification and symbolic display’ (Schön and Rein 1994, 32, cf.; Entman 1993; Gallo-Cruz 2012). However, the interactional framing literature, we use here, revolves around the function of actors making meaning together in interaction with each other (Dewulf and Bouwen 2012; Dodge 2015). Specifically, we follow Dewulf and Bouwen (2012, 169), who define framing as ‘the dynamic enactment and alignment of meaning in ongoing interactions’. In this understanding, framing is finding a consensus among actors over the meaning of a (policy) situation instead of doing so individually. We understand the interactional framing mechanisms Dewulf and Bouwen (2012) propose as processes initiated by an actor for meaning-making, and may also be used consciously in an instrumental way.

Figure 2. Flow chart of Interpretive Policy Entrepreneur characteristics.

Figure 3. Framing interaction mechanisms (adapted from Dewulf and Bouwen 2012).

Frame Constructs by Level of Analysis

Source: PUTTING FRAMING IN PERSPECTIVE: A REVIEW OF FRAMING AND FRAME ANALYSIS ACROSS THE MANAGEMENT AND ORGANIZATIONAL LITERATURE

Source: PUTTING FRAMING IN PERSPECTIVE: A REVIEW OF FRAMING AND FRAME ANALYSIS ACROSS THE MANAGEMENT AND ORGANIZATIONAL LITERATURE

Source: Integrated Framing: A Micro to Macro Case for The Landscape

Narratives, Frames, and Settings

Source: Narrative Frames and Settings in Policy Narratives

A unique aspect of the Narrative Policy Framework (NPF) is that it holds in the balance a social construction ontology with an objective epistemology. According to the NPF, policy realities are socially constructed through a particular perspective in a narrative, and our understanding of how these narratives operate in the policy space can be measured empirically through narrative elements and strategies (Shanahan, Jones, McBeth, and Radaelli, 2017). The NPF contends that empirically understanding the social construction of policy realities sheds light on enduring policy process questions such as why policy arenas remain intractable, how coalition learning and coordination occurs, and, ultimately, how and under what conditions policies change.

To address these broad research inquiries, much of the previous NPF research has focused on singular narrative elements such as characters (e.g., Weible, Olofsson, Costie, Katz, and Heikkila, 2016) and plot (e.g., Shanahan, Jones, McBeth, and Lane, 2013) as well as the narrative strategies of causal mechanism (e.g., Shanahan, Adams, Jones, and McBeth, 2014), distribution of costs and benefits (e.g., McBeth, Shanahan, Arnell, and Hathaway, 2007) and policy beliefs (Shanahan, Jones, and McBeth, 2011). Importantly, these elements and strategies have been generally studied as isolates; the next generation of NPF scholarship is beginning to explore how these narrative components array within the story, to proffer a particular policy perspective. What has not been studied or specified is the role of the narrative element settings in shaping the realities constructed in policy narratives, particularly with how characters array in different settings and how settings are situated within frames. By focusing on the nested nature of characters, settings, and frames, this study aims to reveal the dynamic workings of narratives in the policy terrain.

Why settings? Settings literally are the perspective given to an audience, whether a broad legalistic backdrop (e.g., a statute or Constitution), an aerial regional view (e.g., a map), or a ground-level geographic place (e.g., a landmark or house). Policy scholars (e.g., Weible 2014) often herald the import of context in understanding policy processes; we argue that a setting is the narrative interpretation of policy context. The policy context may include a particular geographic and/or political realm, but a narrative setting provides a particular viewpoint of this context. Such a backdrop delimits what the audience experiences of the narrative, whether the setting is micro (in a room) or macro (aerial view). In turn, settings come alive through the action of the characters. Thus, not only understanding and operationalizing settings, but also linking two narrative elements—characters and settings—are new steps in NPF research.

Why frames? How frames operate in or around narratives has been an issue over which NPF architects have puzzled. Functionally, frames and narratives have similar meaning-making cognitive processes (Jones and Song, 2014) and both shape people’s opinions about policy issues. Crow and Lawlor (2016) add that frames form the central organizing idea and turn facts into a story by selecting and emphasizing some attributes over others, as other framing and policy scholars note (e.g., Stone 2012; McCombs and Ghanem, 2001; Gamson and Madigliani, 1989; Druckman, 2001a). Thus, frames are important and shape the parameters in which narratives unfold. However, are there multiple narratives within one frame? Are divergent narratives housed within the same frame? Does one narrator use multiple frames? Answering these questions will help to shed light on the import of narratives in the context of frames.

My Related Posts

Erving Goffman: Dramaturgy of Social Life

Key sources of Research

Perspectives on Framing

edited by Gideon Keren

2011

Identifying Media Frames and Frame Dynamics Within and Across Policy Issues

Amber E. Boydstun, University of California, Davis Justin H. Gross, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Philip Resnik, University of Maryland, College Park Noah A. Smith, Carnegie Mellon University

September 16, 2013

Tracking the Development of Media Frames within and across Policy Issues

Amber E. Boydstun, University of California, Davis∗

Dallas Card, Carnegie Mellon University

Justin H. Gross, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Philip Resnik, University of Maryland, College Park

Noah A. Smith, Carnegie Mellon University

August 19, 2014

Levels of Information: A Framing Hierarchy

Shlomi Sher Department of Psychology University of California, San Diego

Craig R. M. McKenzie

Rady School of Management and Department of Psychology University of California, San Diego

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.176.189&rep=rep1&type=pdf

From Policy “Frames” to “Framing”: Theorizing a More Dynamic, Political Approach.

van Hulst, M. J., & Yanow, D. (2016).

The American Review of Public Administration, 46(1), 92–112.

The Framing Theory

Frames

IDEAS, POLITICS, AND PUBLIC POLICY

John L. Campbell

Department of Sociology, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire 03755,

e-mail: john.l.campbell@dartmouth.edu

Annu.Rev. Sociol. 2002. 28:21-38

doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.14111

Click to access Ideas,%20behavior%20and%20politics%20review.pdf

Framing Shale Gas for Policy-Making in Poland,

Aleksandra Lis & Piotr Stankiewicz (2016):

Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning,

DOI: 10.1080/1523908X.2016.1143355

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2016.1143355

Donald Schon

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donald_Schön

Frame Reflection: Toward the Resolution of Intractable Policy Controversies

By Donald A. Schon and Martin Rein

Summary written by Conflict Research Consortium Staff

https://www.beyondintractability.org/bksum/schon-frame

Contesting media frames and policy change

The influence of media frames of immigration policy-related incidents contesting dominant policy frames on changes in Dutch immigration policies

Rianne Dekker & Peter Scholten Department of Public Administration Erasmus University Rotterdam P.O. Box 1738

3000 DR Rotterdam r.dekker@fsw.eur.nl

Framing Resilience. From a Model-based Approach to a Management Process☆

Procedia Economics and Finance

Volume 18, 2014, Pages 425-430

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212567114009599

Neighborhood, City, or Region: Deconstructing Scale in Planning Frames

By Kate Lowe

Reframing Problematic Policies

Martin Rein

The Oxford Handbook of Political Science Edited by Robert E. Goodin

Print Publication Date: Jul 2011

Online Publication Date: Sep 2013

DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199604456.013.0046

From Policy “Frames” to “Framing”

van Hulst, M.J.; Yanow, Dvora

The American Review of Public Administration, 46(1), 92–112

2016

Frame Analysis in Environmental Conflicts: The case of ethanol production in Brazil

Ester Galli

PhD Dissertation 2011

KTH – Royal Institute of Technology

School of Industrial Engineering and Management Division of Industrial Ecology

100 44 Stockholm

Donald Schon (Schön): learning, reflection and change

Chris Argyris: theories of action, double-loop learning and organizational learning

Reframing Policy Discourse

Martin Rein and Donald Schön

In book The Argumentative Turn in Policy Analysis and Planning

Edited by Frank Fischer and John Forester 1993

FRAMING CONTESTS: STRATEGY MAKING UNDER UNCERTAINTY

Sarah Kaplan

University of Pennsylvania, Wharton School 3620 Locust Walk, Suite 2019 Philadelphia, PA 19104-6370 215-898-6377 slkaplan@wharton.upenn.edu

Frame Reflection: A Critical Review of US Military Approaches to Complex Situations

Ben Zweibelson, Major, US Army

Grant Martin, Lieutenant Colonel, US Army

Dr. Christopher Paparone, Colonel (retired), US Army

Identifying policy frames through semantic network analysis : an examination of nuclear energy policy across six countries

Shim, J, Park, C and Wilding, M

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s1107701592113

Click to access Semantic%20network%20for%20nuclear%20energy%20policy%20_%20Accepted%20version.pdf

Critical Frame Analysis:

A Comparative Methodology for the ‘Quality in Gender+ Equality Policies’ (QUING) project

Tamas Dombos

Click to access cps-working-paper-critical-frame-analysis-quing-2012.pdf

Integrated Framing: A Micro to Macro Case for The Landscape

*Filip Aggestam

Department of Environmental Engineering, University of Natural Resources and Life sciences, Austria

Submission: February 22, 2017; Published: March 21, 2017

*Corresponding author: Filip Aggestam, Department of Environmental Engineering, University of Natural Resources and Life sciences, Vienna,

Austria,

Volume 2 Issue 1 – March 2017

DOI: 10.19080/IJESNR.2017.02.555578

Int J Environ Sci Nat Res

https://juniperpublishers.com/ijesnr/IJESNR.MS.ID.555578.php

Where is urban food policy in Switzerland? A frame analysis

Heidrun Moschitz

Department of Socio-economics, Research Institute of Organic Agriculture, Frick, Switzerland

INTERNATIONAL PLANNING STUDIES, 2018

VOL. 23, NO. 2, 180–194 https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2017.1389644

Framing Environmental Health Decision-Making: The Struggle over Cumulative Impacts Policy

by Devon C. Payne-Sturges 1,*,†, Thurka Sangaramoorthy 2,†OrcID and Helen Mittmann 2,3

1

Maryland Institute for Applied Environmental Health, School of Public Health, University of Maryland, 2234 L SPH, 255 Valley Drive, College Park, MD 20742, USA

2

Department of Anthropology, University of Maryland, 1111 Woods Hall, 4302 Chapel Lane, College Park, MD 20742, USA

3

Department of Health Policy and Management, Milken Institute School of Public Health, George Washington University, 950 New Hampshire Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20052, USA

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18(8), 3947; https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083947

Received: 14 March 2021 / Revised: 5 April 2021 / Accepted: 7 April 2021 / Published: 9 April 2021

https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/8/3947/htm

Narrative and Frame Analysis: Disentangling and Refining Two Close Relatives by Means of a Large Infrastructural Technology Case

Ewert J. Aukes, Lotte E. Bontje & Jill H. Slinger

FQS

Volume 21, No. 2, Art. 28 – May 2020

https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/3422

https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/3422/4620

Framing in policy processes: A case study from hospital planning in the National Health Service in England,

Jones, L., Exworthy, M.,

Social Science & Medicine (2014),

doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.11.046

Click to access Jones_Exworthy_Framing_policy_processes_Social_Science_Medicine_2014.pdf

The Constructionist Approach to Framing: Bringing Culture Back In

Baldwin Van Gorp

Department of Communication Science, Radboud University Nijmegen, 6500 HC Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Journal of Communication ISSN 0021-9916

Framing Public Issues

Framework Institute

Framing mechanisms: the interpretive policy entrepreneur’s toolbox,

Ewert Aukes, Kris Lulofs & Hans Bressers (2017):

Critical Policy Studies,

DOI: 10.1080/19460171.2017.1314219

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2017.1314219

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/19460171.2017.1314219

Chapter 23: Between representation and narration: analysing policy frames

Handbook of Critical Policy Studies

Edited by Frank Fischer, Douglas Torgerson, Anna Durnová and Michael Orsini

Published in print: 18 Dec 2015

ISBN: 9781783472345e

ISBN: 9781783472352

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4337/9781783472352

https://www.elgaronline.com/view/edcoll/9781783472345/9781783472345.00033.xml

Putting Framing in Perspective: A Review of Framing and Frame Analysis across the Management and Organizational Literature

Joep P. Cornelissen and Mirjam D. Werner

Published Online: 1 Jan 2014

https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2014.875669

Academy of Management Annals VOL. 8, NO. 1

https://journals.aom.org/doi/full/10.5465/19416520.2014.875669

The sense of it all: Framing and narratives in sensegiving about a strategic change.

Logemann, M., Piekkari, R., & Cornelissen, J. (2019).

Long Range Planning, 52(5), [101852]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2018.10.002

The Aesthetics of Story-telling as a Technology of the Plausible

Esther Eidinow (Nottingham) and Rafael Ramirez (Oxford)

From Interactions to Institutions: Microprocesses of Framing and Mechanisms for the Structuring of Institutional Fields

Barbara Gray

Jill M. Purdy

University of Washington Tacoma, jpurdy@uw.edu

Shahzad (Shaz) Ansari

2015

Placing Strategy Discourse in Context: Sociomateriality, Sensemaking, and Power.

Balogun, J., Jacobs, C., Jarzabkowski, P., Mantere, S. and Vaara, E. (2014).

Journal of Management Studies, 51(2), pp. 175-201. doi: 10.1111/joms.12059

https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/8142/1/

Are Logics Enough? Framing as an Alternative Tool for Understanding Institutional Meaning Making

Jill Purdy

Milgard School of Business University of Washington Tacoma

Shaz Ansari

Cambridge Judge Business School University of Cambridge

Barbara Gray

Smeal College of Business The Pennsylvania State University

Do Scale Frames Matter? Scale Frame Mismatches in the Decision Making Process of a “Mega Farm” in a Small Dutch Village

Maartje van Lieshout 1, Art Dewulf 2, Noelle Aarts 3,4 and Catrien Termeer 5

1PhD candidate Public Administration and Policy Group, Wageningen University, 2Assistant professor Public Administration and Policy Group Wageningen University, 3Associate professor Communication Science Group Wageningen University, 4Professor Strategic Communication University of Amsterdam, 5Professor of Public Administration and Policy Wageningen University

http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol16/iss1/art38/

The End of Framing as we Know it . . . and the Future of Media Effects

Michael A. Cacciatore

Department of Advertising and Public Relations University of Georgia

Dietram A. Scheufele

Department of Life Sciences Communication University of Wisconsin and Annenberg Public Policy Center, University of Pennsylvania

Shanto Iyengar

Department of Communication and Department of Political Science Stanford University

Mass Communication and Society, 19:7–23, 2016

Reframing as a Best Practice: The Priority of Process in Highly Adaptive Decision Making.

Dr. Gary Peters

March 24, 2008

Strategic Frame Analysis & Policy Making – Frameworks Institute

The Art and Science of Framing an Issue

Chapter 16: Frames and framing in policymaking

Handbook on Policy, Process and Governing

Edited by H. K. Colebatch and Robert Hoppe

Published in print: 28 Dec 2018

ISBN: 9781784714864e

ISBN: 9781784714871

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784714871

Pages: c 528

https://www.elgaronline.com/view/edcoll/9781784714864/9781784714864.00024.xml

Frame Reflection: Toward the Resolution of Intractrable Policy Controversies

Paperback – June 29, 1995

by Donald A. Schon (Author)

Narrative Frames and Settings in Policy Narratives

Kate French (kfrench406@gmail.com) Elizabeth A. Shanahan (shanahan@montana.edu)* Eric D. Raile (eric.raile@monatan.edu) Jamie McEvoy (Jamie.mcevoy@montana.edu)

Montana State University

Heuristics for practitioners of policy design: Rules-of-thumb for structuring unstructured problems

Robert Hoppe

University of Twente, The Netherlands

Public Policy and Administration

0(0) 1–25 / 2017

Competitive Framing in Political Decision Making (2019)

in: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics

Analysis of Framing on the Public Policies from the View of Rein & Schoen Approach

Challoumis, Constantinos,

(November 17, 2018).

Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3286338 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3286338

Policy framing in the European Union

- June 2007

- Journal of European Public Policy 14(4):654-666

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/248990447_Policy_framing_in_the_European_Union

Media in the Policy Process: Using Framing and Narratives to Understand Policy Influences

Deserai A. Crow, Andrea Lawlor

First published: 07 September 2016

https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12187

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/ropr.12187

In the frame: how policy choices are shaped by the way ideas are presented

11th May 2018

Policy Framing Analysis.

Daviter F. (2011)

In: Policy Framing in the European Union.

Palgrave Studies in European Union Politics. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230343528_2

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057%2F9780230343528_2

Framing and the health policy process: a scoping review

Adam D Koon,*Benjamin Hawkins, and Susannah H Mayhew

Health Policy Plan. 2016 Jul; 31(6): 801–816.

Published online 2016 Feb 11.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4916318/

Framing Shale Gas for Policy-Making in Poland

ALEKSANDRA LIS∗ & PIOTR STANKIEWICZ∗∗

∗Institute of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan, Poznan ́, Poland

∗∗Institute for Sociology, Nicholas Copernicus University in Torun, Torun ́, Poland

Frame-critical policy analysis and frame-reflective policy practice.

Rein, M., Schön, D.

Knowledge and Policy 9, 85–104 (1996).

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02832235

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02832235

The Oxford Handbook of Public Policy, Volume 3

edited by Michael Moran, Martin Rein, Robert Edward Goodin, Robert E. Goodin, Professor of Urban Studies Martin Rein

Reframing Problematic Policies

Martin Rein

The Oxford Handbook of Political Science

Edited by Robert E. Goodin

Print Publication Date: Jul 2011

Online Publication Date: Sep 2013

DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199604456.013.0046

Framing and Feedback

Constantinos Challoumis Κωνσταντίνος Χαλλουμής

National and Kapodistrian University of Athens

Date Written: November 24, 2018

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3289905

Power to the Frame: Bringing Sociology Back to Frame Analysis

- June 2011

- European Journal of Communication 26(2):101-115

Authors:

5 thoughts on “Frames, Communication, and Public Policymaking”