From Systems to Complex Systems

I have studied complex systems science from following teachers:

- Yaneer Bar Yam of NECSI: Physical, Biological, and Social Systems

- Scott Page of University of Michigan: Model Thinking: Complex Systems in Economics and Social/Political Sciences.

- Melanie Mitchell of Santa Fe Institute: Introduction to Complex Systems

- Michael Kearns of University of Pennsylvania: Networked Life: Science of Networks

- Ravi Iyenger of Mount Sinai Icahn School of Medicine: Introduction to Systems Biology

- Perry Mehrling of Columbia University/INET: Economics of Money and Banking

- John Sterman of MIT: Business Dynamics: Using Systems Dynamics

Key Terms

- Complex Systems

- Networks

- Interaction

- Agents

- Bottom Up Modeling

- Agent Based Modeling

- Netlogo

- New England Complex Systems Institute (NECSI)

- Santa Fe Institute (SFI)

- Yaneer Bar Yam

- Scott Page

- Melanie Mitchell

- Network Science

- Dynamical Systems

- Cellular Automata

- Artifical Life (A-Life)

- Anti Fragility

- Agility

- Learning

- Adaptability

- Resilience

- Synchronization

- Mark Newman

- Albert Laszlo Barabasi

- John Sterman

- Small World Networks

- Scale Free Networks

- Hierarchy

- Boundaries

- Stephen Wolfram

- Stuart Kaufman

- Increasing Retuns

- Path Dependence

- J Doyne Farmer

- W. Brian Arthur

- Duncan Watts

- Eugene Stanley

- Six Degrees of Separation

- Emergence

- Non Linear Dynamics

- Competition and Cooperation

What are Complex Systems?

Source: A Brief History of Systems Science, Chaos and Complexity

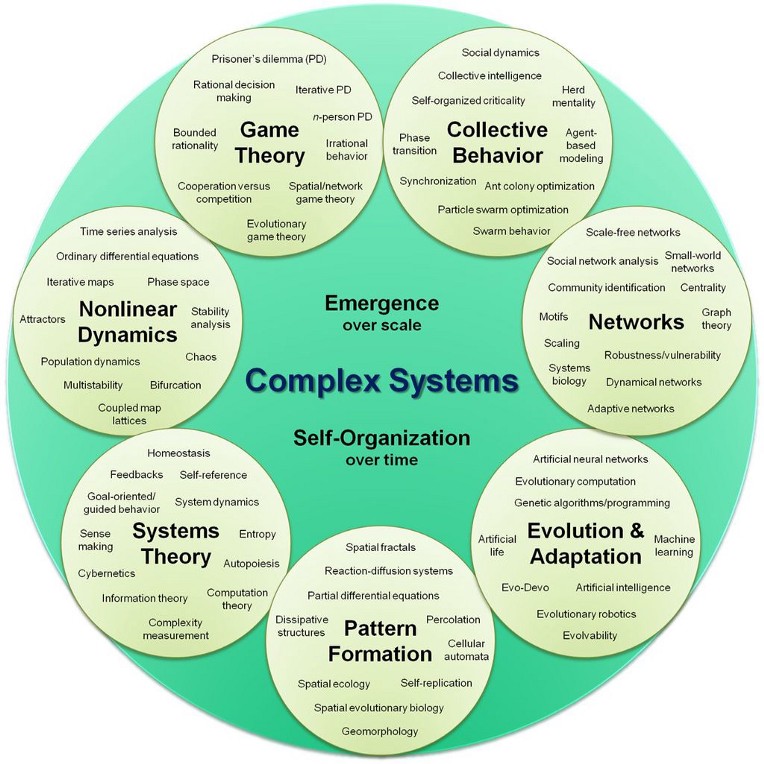

Key Topics in Complex Systems

Sources: Complex Systems: A Survey

- Lattices and Networks

- Dynamical Systems

- Discrete Systems and Cellular Automata

- Scaling and Criticality

- Adaptation and Game Theory

- Information Theory

- Computational Complexity

- Agent based Modeling

- Chaos and Fractals

- Spontaneous Order and Synchronization

Complex Systems

The original journal devoted to the science, mathematics and engineering of systems with simple components but complex overall behavior; publishes high-quality articles that focus on, but are not limited to, the following areas:

- Dynamic, topological and algebraic aspects of cellular automata and discrete dynamical systems

- Complex systems and complexity theory

- Algorithmic complexity and information theory

- Emergent properties of dynamical systems

- Formal languages, grammars and automata

- Algorithmic information dynamics

- Symbolic dynamics and connections to continuous systems

- Tilings, rewriting and substitution systems

- Computability theory

- Synchronous versus asynchronous models

- Applications of automata to areas such as machine and deep learning, physics, biology, social sciences and others

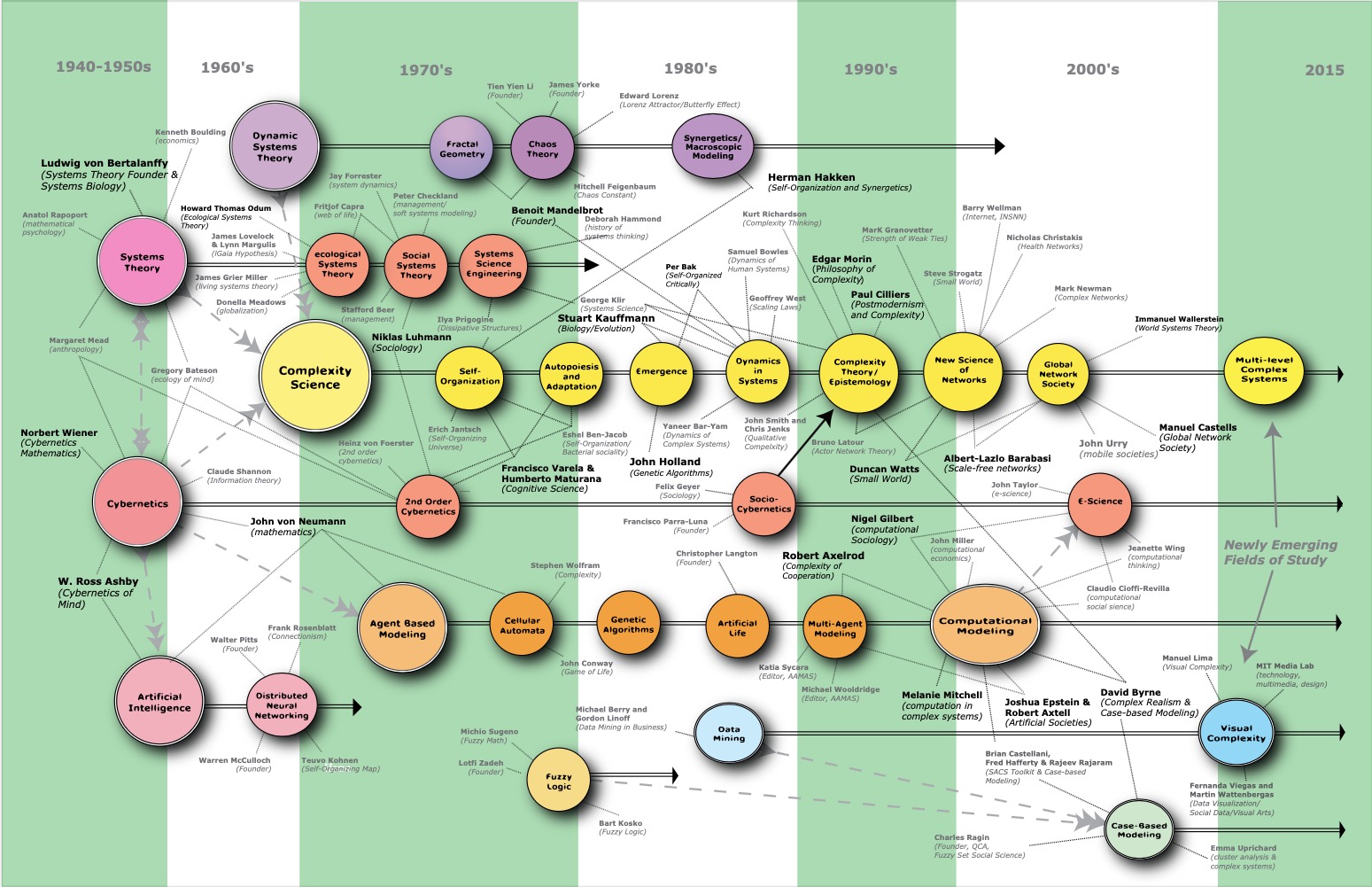

Source: A Brief History of Systems Science, Chaos and Complexity

History of Systems and Complex Systems

Source: A Brief History of Systems Science, Chaos and Complexity

My Related Posts

Micro Motives, Macro Behavior: Agent Based Modeling in Economics

Systems Biology: Biological Networks, Network Motifs, Switches and Oscillators

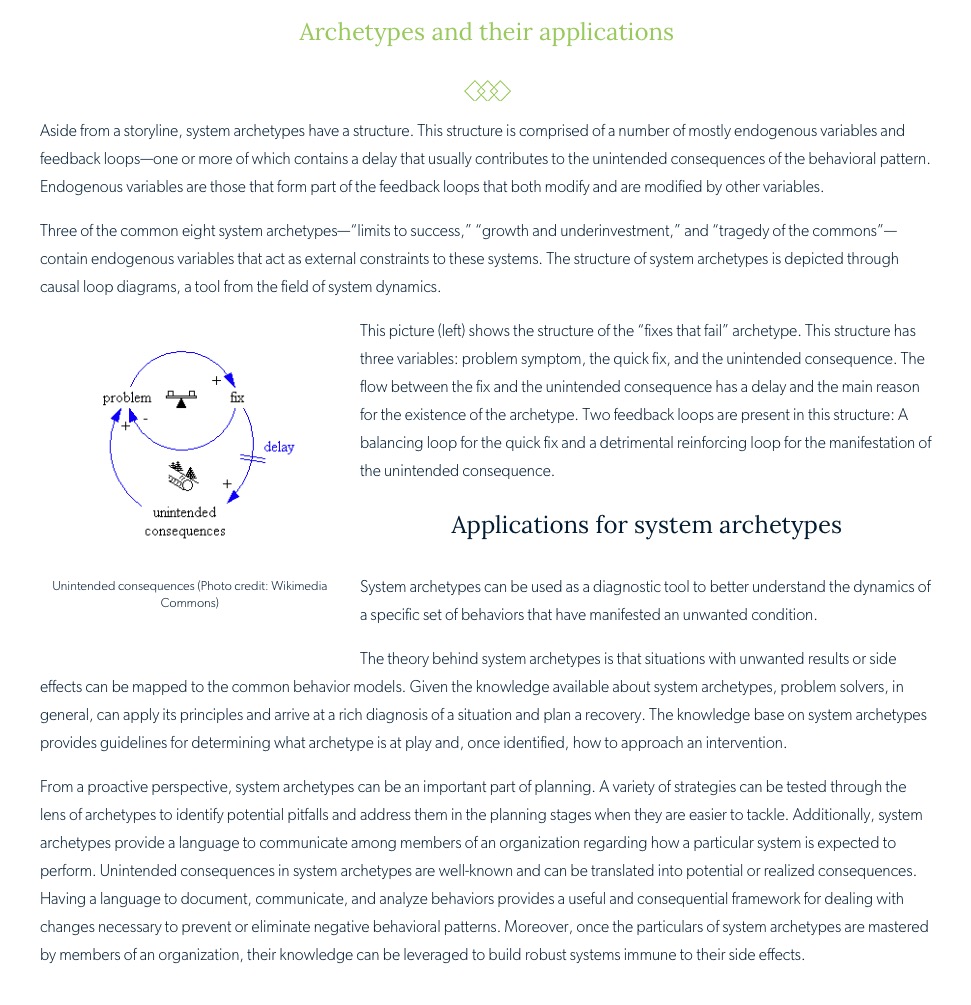

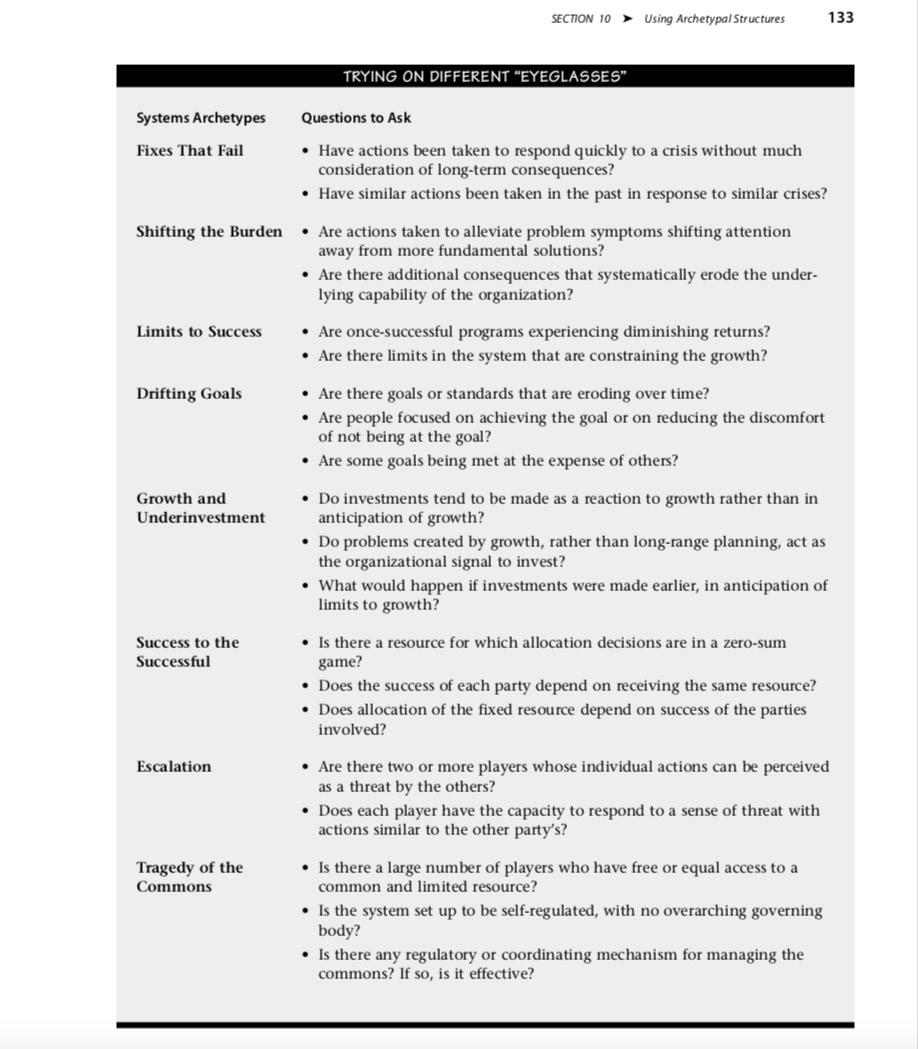

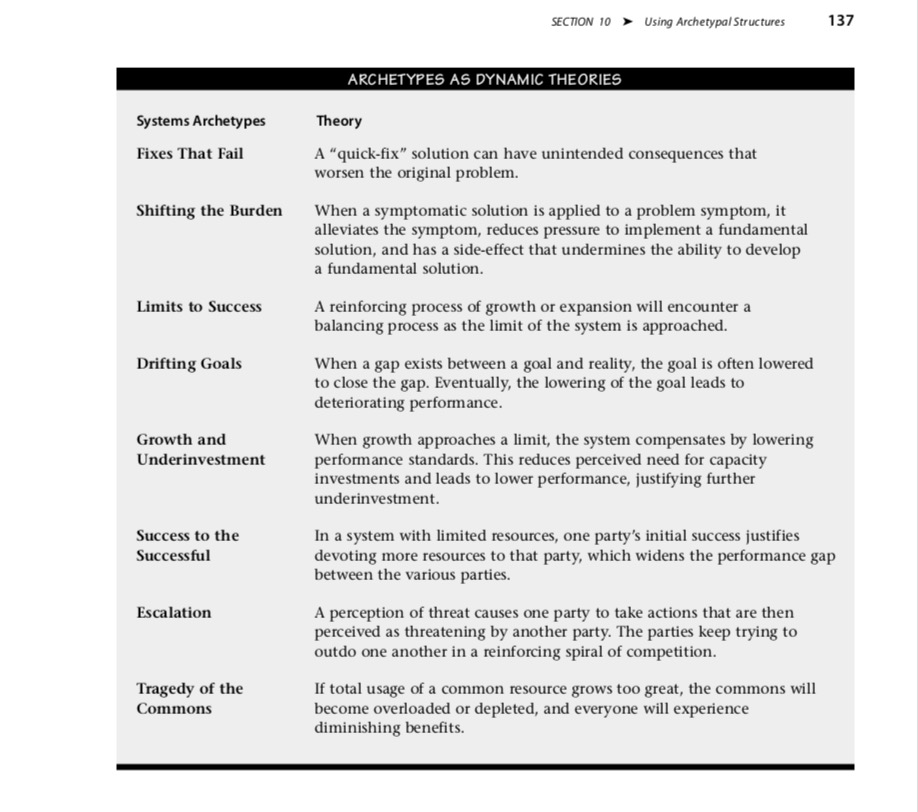

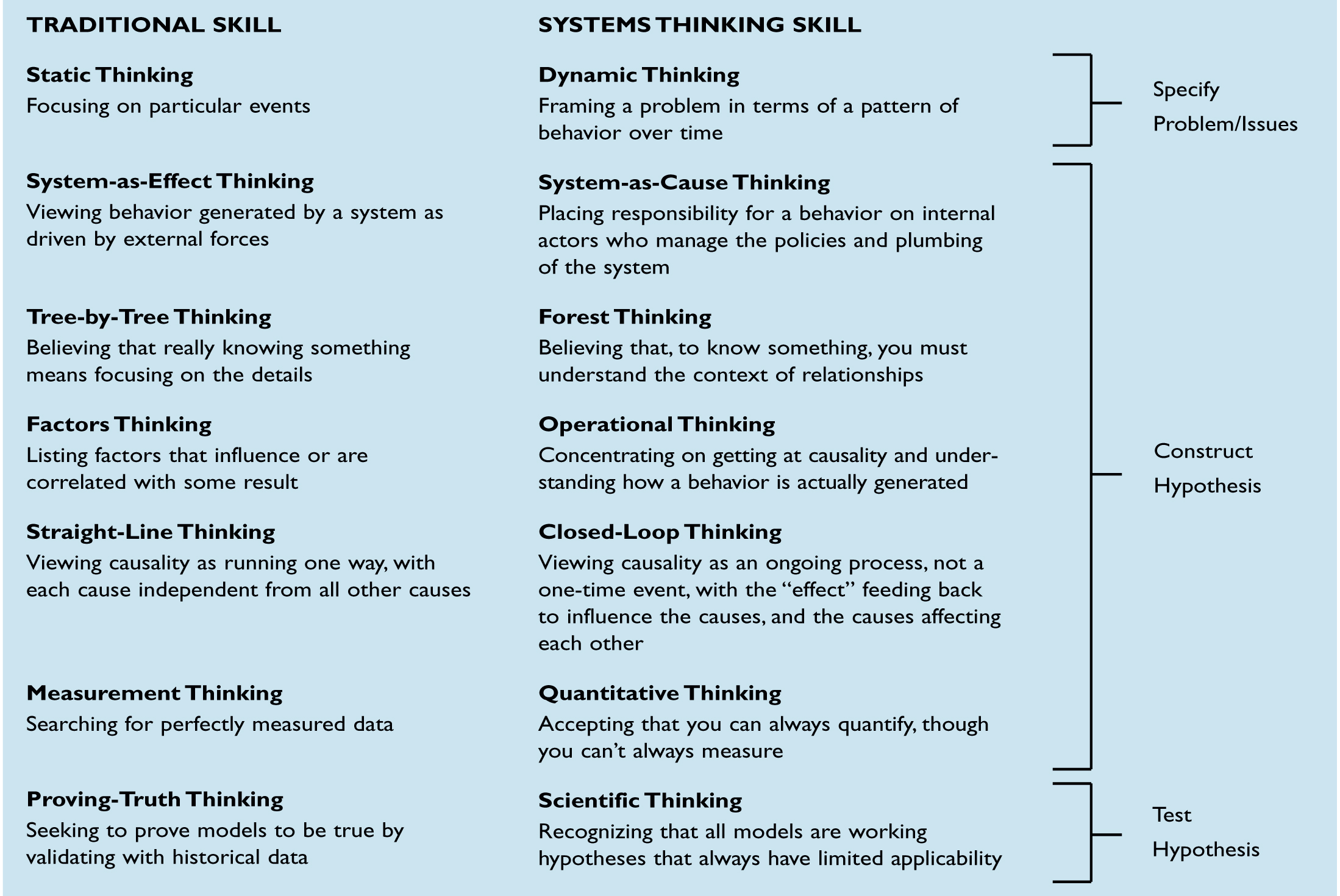

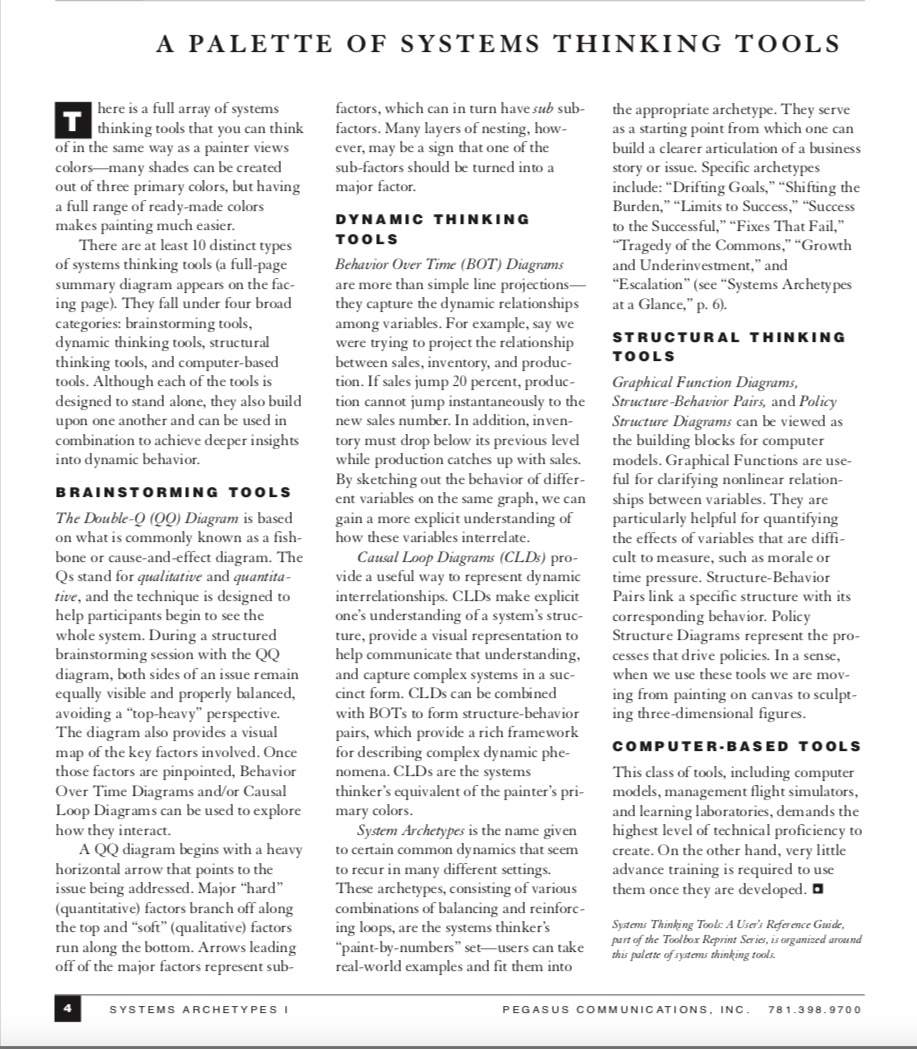

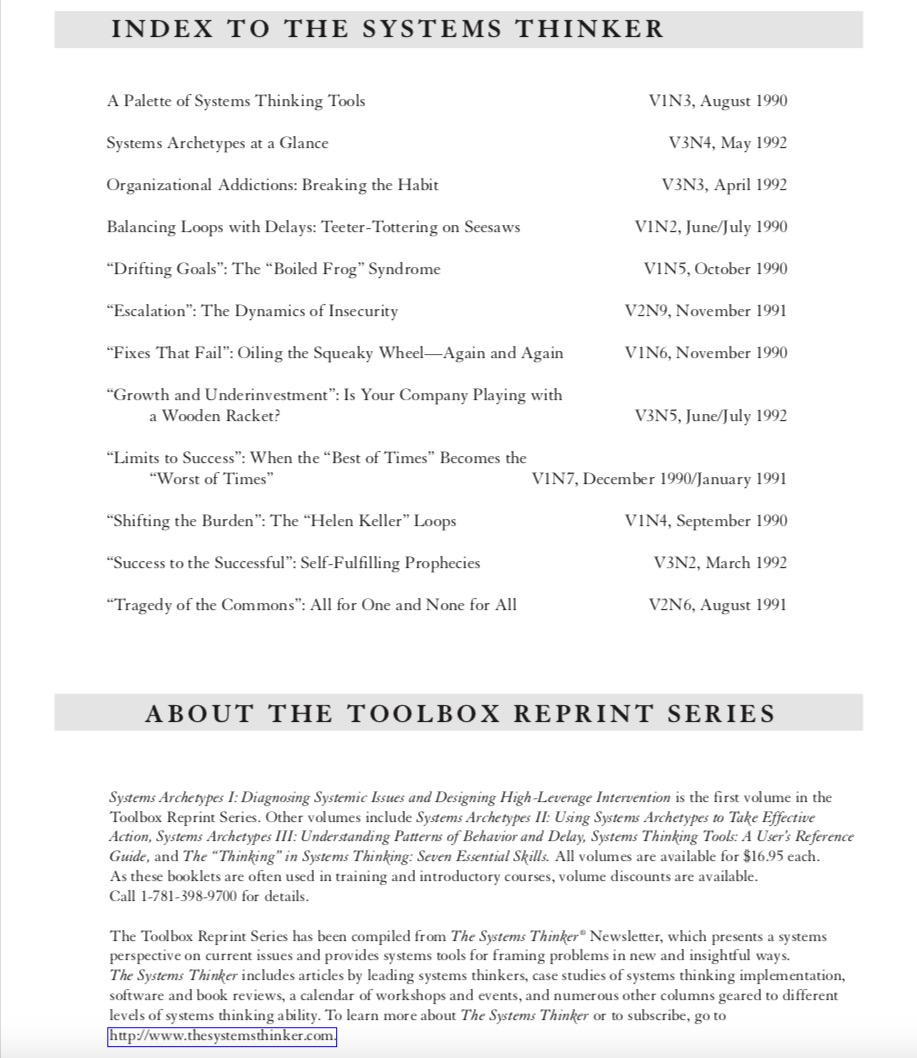

System Archetypes: Stories that Repeat

Contagion in Financial (Balance sheets) Networks

Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, Circular and Cumulative Causation in Economics

Increasing Returns and Path Dependence in Economics

Interdependence in Payment and Settlement Systems

Classical roots of Interdependence in Economics

Feedback Thought in Economics and Finance

Jay W. Forrester and System Dynamics

Balance Sheets, Financial Interconnectedness, and Financial Stability – G20 Data Gaps Initiative

Oscillations and Amplifications in Demand-Supply Network Chains

Credit Chains and Production Networks

Wassily Leontief and Input Output Analysis in Economics

Key Sources of Research

An Introduction to Complex Systems Science and Its Applications

Alexander F. Siegenfeld 1,2 and Yaneer Bar-Yam2

1Department of Physics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA 2New England Complex Systems Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA

Hindawi

Complexity

Volume 2020, Article ID 6105872, 16 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6105872

https://necsi.edu/an-introduction-to-complex-systems-science-and-its-applications

https://www.hindawi.com/journals/complexity/2020/6105872/

COMPLEXITY RISING:

From Human Beings to Human Civilization, a Complexity Profile

NECSI

https://necsi.edu/complexity-rising-from-human-beings-to-human-civilization-a-complexity-profile

MULTISCALE COMPLEXITY/ENTROPY

Advances in Complex Systems Vol. 07, No. 01, pp. 47-63 (2004)

https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219525904000068

GENERAL FEATURES OF COMPLEX SYSTEMS

Y. Bar-Yam

New England Complex Systems Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA

The why, how, and when of representations for complex systems

Leo Torres

leo@leotrs.com

Network Science Institute, Northeastern University

Danielle S. Bassett

dsb@seas.upenn.edu

Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania

Ann S. Blevins

annsize@seas.upenn.edu

Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania

Tina Eliassi-Rad

tina@eliassi.org

Network Science Institute and Khoury College of Computer Sciences, Northeastern University

June 5, 2020

Santa Fe Institute

Strategy and Complex Systems

wayne.smith@csun.edu

Thursday, December 10, 2020

Learning to Live with Complexity

by

HBR (September 2011)

MULTIDISCIPLINARY COMPLEX SYSTEMS RESEARCH

Report from an NSF Workshop in May 2017

Kimberly A. Gray, Northwestern University, Co-Chair

Adilson E. Motter, Northwestern University, Co-Chair

Center for Study of Complex System

University of Michigan

Complex Systems Theory

1988 Stefan Wolfram

What is a complex system?

- June 2013

- European Journal for Philosophy of Science 3(1)

- Project: Complexity Science

Authors:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/50210075_What_is_a_complex_system

Learning in and about complex systems

MIT System Dynamics

First published: Summer ‐ Autumn (Fall) 1994 https://doi.org/10.1002/sdr.4260100214

Complex Systems

Science for the 21st Century

A U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science Workshop

Effectiveness of Leadership Decision-Making in Complex Systems

by Leonie Hallo 1,*, Tiep Nguyen 2, Alex Gorod 1 and Phu Tran 2

1Adelaide Business School, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia 5000, Australia

2Transport Economic Faculty, Ho Chi Minh University of Transport, Ho Chi Minh 700000, Vietnam

*Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Systems2020, 8(1), 5; https://doi.org/10.3390/systems8010005

Received: 4 January 2020 / Revised: 2 February 2020 / Accepted: 7 February 2020 / Published: 12 February 2020

https://www.mdpi.com/2079-8954/8/1/5

Debate the Issues: Complexity and policy makIng

OECD

OECD Insights, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264271531-en.

The Rising Complexity of the Global Economy

OECD Insights

http://oecdinsights.org/2016/09/02/the-rising-complexity-of-the-global-economy/

Introduction to the Theory of Complex Systems

Stefan Thurner, Rudolf Hanel, and Peter Klimek

Medical University of Vienna, Austria

Modeling Complex Systems

Nino Boccara

Springer

Taming Complexity

Make sure the benefits of any addition to an organization’s systems outweigh its costs. by

HBR Magazine (January–February 2020)

https://hbr.org/2020/01/taming-complexity

How do I manage the complexity in my organization?

Suzanne Heywood

Rubén Hillar

David Turnbull

McKinsey 2010

Agility: The antidote to complexity

Deloitte 2021 Global Chief Procurement Officer Survey

Unlocking The True Value Of Digital Transformation

Modernize your IT Services to tackle rising complexity

A Forrester Consulting

Thought Leadership Paper Commissioned By Tata Consultancy Services

June 2020

WHAT MAKES A SYSTEM COMPLEX?

AN APPROACH TO SELF ORGANIZATION AND EMERGENCE

Michel Cotsaftis

LACSC/ECE mcot@ece.fr

An introduction to complex system science ∗

Lecture notes for the use of master students in Computer Science and Engineering

Andrea Roli andrea.roli@unibo.it

DISI – Dept. of Computer Science and Engineering Campus of Cesena

Alma Mater Studiorum Universita` di Bologna

What is a Complex System?

James Ladyman, James Lambert

Department of Philosophy, University of Bristol, U.K.

Karoline Wiesner

Department of Mathematics and Centre for Complexity Sciences, University of Bristol, U.K.

(Dated: March 8, 2012)

Overview of Complex Systems

Principles of Complex Systems | @pocsvox CSYS/MATH 300, Fall, 2013 | #FallPoCS2013

Prof. Peter Dodds| @peterdodds

Introduction to the Theory of Complex Systems

- R. Hanel, S. Thurner, P. Klimek

- Published 2018

Click to access book-thurner18.pdf

Foundations of Complex-system Theories: In Economics, Evolutionary Biology …

By Sunny Y. Auyang

From simplistic to complex systems in economics

John Foster*

Cambridge Journal of Economics 2005, 29, 873–892

doi:10.1093/cje/bei083

Complex Systems: A Survey

M. E. J. Newman

Department of Physics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 and

Center for the Study of Complex Systems, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109

Designing to learn about Complex Systems

Click to access hmelo_00_designing_to_learn_complex.pdf

Complex systems: Network thinking

Melanie Mitchell

Artificial Intelligence 170 (2006) 1194–1212

Statecharts: a visual formalism for complex systems

Science of Computer Programming

Volume 8, Issue 3, June 1987, Pages 231-274

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0167642387900359

Control Principles of Complex Networks

Yang-YuLiu1,2 andAlbert-L ́aszl ́oBarab ́asi3,2,4,5 1Channing Division of Network Medicine,

Brigham and Women’s Hospital,

Harvard Medical School,

Boston, Massachusetts 02115,

USA

2Center for Cancer Systems Biology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts 02115,

USA

3Center for Complex Network Research and Departments of Physics, Computer Science and Biology,

Northeastern University,

Boston, Massachusetts 02115,

USA

4Department of Medicine,

Brigham and Women’s Hospital,

Harvard Medical School,

Boston, Massachusetts 02115,

USA

5Center for Network Science,

Central European University, Budapest 1052,

Hungary

(Dated: March 15, 2016)

Physical approach to complex systems

Jarosław Kwapień a,∗, Stanisław Drożdż a,b

a Complex Systems Theory Department, Institute of Nuclear Physics, Polish Academy of Sciences, PL–31-342 Kraków, Poland

b Institute of Computer Science, Faculty of Physics, Mathematics and Computer Science, Cracow University of Technology, PL–31-155 Kraków, Poland

Physics Reports 2011

Dynamics of Complex Systems (Studies in Nonlinearity)

Yaneer Bar-Yam,

Addison-Wesley, New York, 1997; ISBN 0-201-55748-7; 800 pp.,

https://necsi.edu/dynamics-of-complex-systems

MODULARITY AND INNOVATION IN COMPLEX SYSTEMS

SENDIL K. ETHIRAJ

The Wharton School of Business

3620 Locust Walk, Suite 2000 University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia PA 19104 Ph. 215-898 1231

Email: sethiraj@wharton.upenn.edu

DANIEL LEVINTHAL University of Pennsylvania

https://journals.aom.org/doi/pdf/10.5465/apbpp.2002.7519521

Complex Systems—A New Paradigm for the Integrative Study of Management, Physical, and Technological Systems

Luis A. Nunes Amaral

Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, McCormick School of Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, amaral@northwestern.edu

Brian Uzzi

Department of Management and Organizations, Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, uzzi@northwestern.edu

MANAGEMENT SCIENCE

Vol. 53, No. 7, July 2007, pp. 1033–1035

issn 0025-1909 eissn 1526-5501 07 5307 1033

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.728.1068&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Boundaries, Hierarchies and Networks in Complex Systems

PAUL CILLIERS

Department of Philosophy University of Stellenbosch Stellenbosch7600 South Africa

Fpc@akad.sun.ac.za

International Journal of Innovation Management, Vol. 5, No. 2 (June 2001) pp. 135–147

Click to access Cilliers-2001-Boundaries-Hierarchies-and-Networks.pdf

Extracting the hierarchical organization of complex systems

Marta Sales-Pardo, Roger Guimera` , Andre ́ A. Moreira, and Luís A. Nunes Amaral*

Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering and Northwestern Institute on Complex Systems, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208

Edited by H. Eugene Stanley, Boston University, Boston, MA, and approved July 22, 2007 (received for review April 23, 2007)

PNAS November 20, 2007 vol. 104 no. 47

Patterned Interactions in Complex Systems: Implications for Exploration.

Rivkin, J. W., & Siggelkow, N. (2007).

Management Science, 53 (7), 1068-1085. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1060.0626

A complex systems approach to constructing better models for managing financial markets and the economy

J. Doyne Farmer1, M. Gallegati2, C. Hommes3, A. Kirman4, P. Ormerod5, S. Cincotti6, A. Sanchez7, and D. Helbing8

1 Santa Fe Institute, 1399 Hyde Park Road, Santa Fe, NM 87501, USA

2 DiSES, Universit Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona, Italy

3 CeNDEF, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands

4 GREQAM, Aix Marseille Universit ́e, EHESS, France

5 Volterra Partners, London and University of Durham, UK

6 DIME-DOGE.I, University of Genoa, Italy

7 GISC, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Spain

8 ETH, Zu ̈rich

Received 1 August 2012 / Received in final form 9 October 2012 Published online 5 December 2012

Eur. Phys. J. Special Topics 214, 295–324 (2012)

THE ONTOLOGY OF COMPLEX SYSTEMS: Levels of Organization, Perspectives, and Causal Thickets*

(Canadian Journal of Philosophy, supp. vol #20, 1994, ed. Mohan Matthen and Robert Ware, University of Calgary Press, 207-274).

by William C. Wimsatt

Department of Philosophy

University of Chicago

January 4, 1994

wwim@midway.uchicago.edu

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.177.6704&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Requisite variety and its implications for the control of complex systems,

Ashby W.R. (1958)

Cybernetica 1:2, p. 83-99.

http://pcp.vub.ac.be/Books/AshbyReqVar.pdf,

Click to access ashbyreqvar.pdf

Weak Links

The Universal Key to the Stability of Networks and Complex Systems

P ́eter Csermely

February 25, 2009

Weak Links: Stabilizers of Complex Systems from Proteins to Social Networks,

by Peter Csermely.

2006 XX, 408 p. 37 illus. 3-540-31151-3. Berlin: Springer, 2006.

An Introduction to Agent-Based Modeling: Modeling Natural, Social, and Engineered Complex Systems with NETLogo

Wilensky, Uri and Rand, William MIT Press: London, 2015

ISBN 978-0262731898 (pb)

Dynamics of Complex Systems: Scaling Laws for the Period of Boolean Networks

Réka Albert and Albert-László Barabási*

Department of Physics, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556

(Received 28 April 1999)

PHYSICAL REVIEW LETTERS

VOLUME 84, NUMBER 24

12 JUNE 2000

Cities as Complex Systems: Scaling, Interactions, Networks, Dynamics

and Urban Morphologies

ISSN 1467-1298

Michael Batty

Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis, University College London, 1-19 Torrington Place, London WC1E 6BT, UK

Email: m.batty@ucl.ac.uk, Web: www.casa.ucl.ac.uk

The Encyclopedia of Complexity & System Science, Springer, Berlin, DE, forthcoming 2008. Date of this paper: February 25, 2008.

Scale invariance and universality: organizing principles in complex systems

H.E. Stanleya;∗, L.A.N. Amarala , P. Gopikrishnana , P.Ch. Ivanova , T.H. Keittb , V. Pleroua

aCenter for Polymer Studies and Department of Physics, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215, USA bNational Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis, 735 State Street, Suite 300,

Santa Barbara, CA 93101, USA

Physica A 281 (2000) 60–68

A pragmatist approach to transdisciplinarity in sustainability research: From complex systems theory to reflexive science

Florin Popa

Mathieu Guillermin

Tom Dedeurwaerdere

Futures

Volume 65, January 2015, Pages 45-56

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2014.02.002

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016328714000391

Extracting and Representing Qualitative Behaviors of Complex Systems in Phase Spaces

Feng Zhao

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE LABORATORY

A.I. Memo No. 1274 Marc]: 1991

What is a Complex System?

James Ladyman, James Lambert

Department of Philosophy, University of Bristol, U.K.

Karoline Wiesner

Department of Mathematics and Centre for Complexity Sciences, University of Bristol, U.K.

(Dated: March 8, 2012)

Click to access LLWultimate.pdf

Modelling and prediction in a complex world

Michael Battya, Paul M. Torrensb,*

aCentre for Advanced Spatial Analysis, University College London, 1 to 19 Torrington Place, London WC1E 6BT, UK

bDepartment of Geography, University of Utah, 260 S. Central Campus Dr., Rm. 270, Salt Lake City, UT 84112-9155, USA

Available online 19 March 2005

Click to access 2005-futures-complexity.pdf

Complex networks

Augmenting the framework for the study of complex systems

THE EUROPEAN PHYSICAL JOURNAL B

L.A.N. Amarala and J.M. Ottino

Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208, USA

Received 12 November 2003

Published online 14 May 2004

Eur. Phys. J. B 38, 147–162 (2004) DOI: 10.1140/epjb/e2004-00110-5

Learning from Evidence in a Complex World

John D. Sterman

Jay W. Forrester Professor of Management and Professor of Engineering Systems Sloan School of Management

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

30 Wadsworth Street, E53-351

Cambridge MA 02142

617.253.1951

jsterman@mit.edu

web.mit.edu/jsterman/www

Revision of May 2005

Forthcoming,

American Journal of Public Health

Click to access LearningFromEvidenceFinal.pdf

INTERDISCIPLINARY DESCRIPTION OF COMPLEX SYSTEMS

7(2), pp. 22-116, 2009 ISSN 1334-4684

Error and attack tolerance of complex networks

R ́eka Albert, Hawoong Jeong, Albert-L ́aszl ́o Barab ́asi

Department of Physics, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556

2000

The Kuramoto model in complex networks

Francisco A. Rodriguesa, Thomas K. DM. Peronb,c,∗, Peng Jic,d,∗, Jürgen Kurthsc,d,e,f

aDepartamento de Matemática Aplicada e Estatística, Instituto de Ciências Matemáticas e de Computação, Universidade de São Paulo, Caixa Postal 668, 13560-970 São Carlos, São Paulo, Brazil

bInstituto de Física de São Carlos, Universidade de São Paulo, Caixa Postal 369, 13560-970, São Carlos, São Paulo, Brazil

cPotsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), 14473 Potsdam, Germany dDepartment of Physics, Humboldt University, 12489 Berlin, Germany eInstitute for Complex Systems and Mathematical Biology, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen AB24 3UE, United Kingdom

fDepartment of Control Theory, Nizhny Novgorod State University, Gagarin Avenue 23, Nizhny Novgorod 606950, Russia

2015

Uncovering the overlapping community structure of complex networks in nature and society

Gergely Palla†‡, Imre Dere ́nyi‡, Ille ́s Farkas†, and Tama ́s Vicsek†‡ †Biological Physics Research Group of HAS, Pa ́zma ́ny P. stny. 1A, H-1117 Budapest, Hungary,

‡Dept. of Biological Physics, Eo ̈tvo ̈s University, Pa ́zma ́ny P. stny. 1A, H-1117 Budapest, Hungary.

System Dynamics:

Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World

John D. Sterman

MIT Sloan School of Management Cambridge MA 02421

617.253.1951 (voice) 617.258.7579 (fax) jsterman@mit.edu web.mit.edu/jsterman/www

April 2002

https://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/102741/esd-wp-2003-01.13.pdf?sequence=1

Complex thinking, complex practice: The case for a narrative approach to organizational complexity

Haridimos Tsoukas and Mary Jo Hatch

Human Relations

[0018-7267(200108)54:8] Volume 54(8): 979–1013: 018452

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.621.6579&rep=rep1&type=pdf

From complex regions to complex worlds.

Holling, C. S. 2004.

Ecology and Society 9(1): 11. [online] URL: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss1/art11

Causal thinking and complex system approaches in epidemiology

Sandro Galea,* Matthew Riddle and George A Kaplan

International Journal of Epidemiology 2010;39:97–106

doi:10.1093/ije/dyp296

Tools and techniques for developing policies for complex and uncertain systems

Steven C. Bankes*

RAND, 1700 Main Street, Santa Monica, CA 90407

http://www.pnas.orgcgidoi10.1073pnas.092081399

PNAS May 14, 2002 vol. 99 suppl. 3 7263–7266

Explaining complex organizational dynamics

Dooley, Kevin J; Van de Ven, Andrew H

Organization Science; May/Jun 1999; 10, 3; ABI/INFORM Global pg. 358

Supply-chain networks: a complex adaptive systems perspective,

Amit Surana , Soundar Kumara , Mark Greaves & Usha Nandini Raghavan (2005)

International Journal of Production Research, 43:20, 4235-4265,

DOI: 10.1080/00207540500142274

Hierarchical organization in complex networks

Erzs ́ebet Ravasz and Albert-La ́szl ́o Baraba ́si

Department of Physics, 225 Nieuwland Science Hall, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA (Dated: February 1, 2008)

Unifying Principles in Complex Systems

Yaneer Bar-Yam New England Complex Systems Institute 24 Mt. Auburn St., Cambridge, MA 02138

General Features of Complex Systems

- January 2002

Authors:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/246294756_General_Features_of_Complex_Systems

Complex Systems

Journal

https://www.complex-systems.com

What is complex systems science?

Santa Fe Institute

https://www.santafe.edu/what-is-complex-systems-science

Complex Systems Modeling: Using Metaphors From Nature in Simulation and Scientific Models

https://homes.luddy.indiana.edu/rocha/publications/complex/csm.html

Complex systems science and brain dynamics

- 1 The Biologically Inspired Neural and Dynamical Systems lab, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, Amherst, MA, USA

- 2 The Program for Evolutionary Dynamics, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA

Front. Comput. Neurosci., 10 September 2010 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fncom.2010.00007

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fncom.2010.00007/full

Evolutionary Psychology, Complex Systems, and Social Theory

Bruce MacLennan

Department of Electrical Engineering & Computer Science University of Tennessee, Knoxville MacLennan@utk.edu

Simulating Complex Systems – Complex System Theories, Their Behavioural Characteristics and Their Simulation

Rabia Aziza, Amel Borgi, Hayfa Zgaya, Benjamin Guinhouya

https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01716055/document

A Brief History of Systems Science, Chaos and Complexity

By Daniel Christian Wahl, originally published by P2P Foundation Blog

September 12, 2019

Economics needs to treat the economy as a complex system

J. Doyne Farmer1,2

1Department of Mathematics, the University of Oxford,

Institute for New Economic Thinking at the Oxford Martin School

2Santa Fe Institute, 1399 Hyde Park road, Santa Fe, NM 87501, USA

May 3, 2012

Understanding Complexity

By Olivier Serrat

ADB 2009

Karl Dodd1,

Karl Dodd1,