Problems at the Intersection of Aesthetics and Ethics

The Intersection of Aesthetics and Ethics

Ever since the publication of Kant’s Critique of Judgment, the concept of taste has been severed from its moral sense and reduced to a merely aesthetic one.1 Since then two trends have predominated in moral philosophy. The first is a rationalist view of ethics, which proposes the need to subsume particular actions under universal laws. Deontological and utilitarian theories both have this paradigm in common. The second is the refraction of this position, which marginalizes any discussion of moral feeling as a psychological question of emotivism or subjectivism.2 This trend of positivism dismisses feelings as mere emotive states, questions of psychology, subjective, and therefore not binding.

In order to recapture the aesthetic dimensions of moral experience, one needs a view of aesthetics that is not limited to reflections on the beautiful and sublime in nature or art and that is not reducible to an allegiance to taste and manners; and one needs a continuity principle that enables reflection on morality to be true to experience. Two process philosophers, Alfred North Whitehead and John Dewey, present a metaphysics of experience which enriches ethics by illustrating the aesthetic dimensions of moral experience. Where the traditions outlined above view reason as the pivotal faculty in navigating the moral landscape, process philosophy emphasizes the aesthetic categories of feeling and imagination as operative in moral experience.

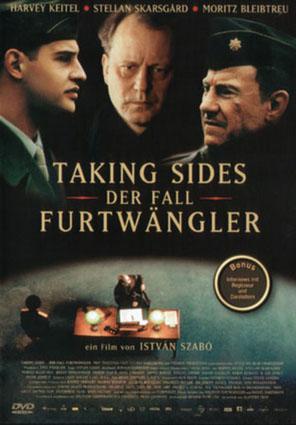

Those skeptical of “aestheticizing morality” often invoke the show-stopping reference to the Nazi Regime, one which consciously and politically recruited aesthetic ideals toward the crystallization of immorality.3 This is the Reductio ad Hitlerum to which the title refers. Fascism and Nazism in particular habituated a marriage between politics and aesthetics, and took up the goal of making politics a triumphant and beautiful spectacle.4 Art, music, and aesthetic symbols were recruited as instruments toward fulfilling this goal.5 Nazi Germany held “countless historical pageants, Volk festivals, military parades, propaganda films, art exhibitions and [erected] grandiose buildings”6 in order to exemplify “the fascist desire to invent mythic imperial pasts and futures,”7 while stirring the passions of the people for its war efforts. The Nazis denounced any allegiance to liberal political texts such as the Versailles Treaty “in favor of decisive political action based on fatal aesthetic criteria — beautiful vs. ugly, healthy vs. degenerate, German vs. Jew.”8 It is warranted to invoke this as the problem for those who “aestheticize” morality. The Nazi problematic, illustrated by an analysis of two films surrounding the immorality of the Nazi Regime, James Ivory’s The Remains of the Day (1993) and István Szabó’s Taking Sides (2001) illuminates the limitations and failures of the tendency to “aestheticize” morality. These films help show the nuances that reside at this tense intersection between aesthetics and ethics. However, tension between aesthetics and ethics, as depicted by the two films, dissolves once one’s understanding of aesthetics ceases to be reductive and narrow.

The aesthetic dimensions of moral experience in the philosophies of Alfred North Whitehead and John Dewey provide a basis for defining the continuity between ethics and aesthetics. For Whitehead, an aesthetic vision which builds on insights of his descriptive metaphysics enables us to see moral experience as aesthetic. For Dewey, the imagination works on the possibilities at hand in order to resolve morally problematic situations, and the grist for the imagination’s mill is experiential, perceptual, and aesthetic, not merely rational or conceptual. Thus, the broad use of aesthetics advocated herein enables us to draw moral distinctions in the face of Nazi atrocities instead of blindly serving the ideal of artistic creation. Nor does it reduce aesthetics to a fetish for manners. Rather, as including imagination, perception, taste, and emotion, an aesthetic orientation to ethics can encompass the limits posed by these films, and it can morally condemn the Nazi Regime and avoid the Hitler-reductio.

A.N. Whitehead at the Intersection

A sketch of Whitehead’s metaphysics is necessary in order to show how the foundations for moral action may be subsumed under the category of aesthetic experience. According to Whitehead’s systematic metaphysics, the world is a process of becoming. It is ultimately composed of self-creating “actual occasions.”9 The act of self-creation is the “concrescence” of an actual entity, “the final real things of which the world is made up.”10 Thus an “entity” describes an occasion or event in the mode of concrescense, the act of an occasion having prehended its environment. Events create themselves by virtue of their interdependence. The mode of relation each entity has toward others and toward its possibilities in general is “feeling.” “Prehensions” are the feelings which each entity has of its environment, which includes the entire universe, as each entity pulsates and vibrates throughout the cosmos in its process of self-creation.11 Since Whitehead holds that relations are more fundamental than substance, these prehensions constitute the actual entity. Where in traditional metaphysics, substance is primary and the relations among substances are described as secondary attributes, in Whitehead’s description entities are internally related, constituted by their relations. In this process metaphysics, relations are not secondary but primary in that they constitute the entities. When an actual entity prehends its environment, the entity constitutes itself and makes itself what it is.12Each entity serves as the subject of its own becoming and the “superject” of others, imparting itself to other entities in their becoming.13 Actual entities, in process metaphysics, are events, occasions in time, and always situated in a complex, interdependent environment of other entities. Thus, Whitehead’s speculative metaphysics is relational, not atomistic.

This speculative picture of reality lends itself to reflections on moral experience, including an account of Whitehead’s theory of value. In Process and Reality, Whitehead’s theory of value uses strong aesthetic language. He describes intensity of experience as “strength of beauty”: the degree of feeling in an occasion’s prehension of its environment. 14 Further, as John Cobb notes, “The chief ingredients [to beautiful experience] are emotional.”15 The actual entity prehends its environment, feeling its aesthetic surrounding in a chiefly emotional comportment. Because the locus of value is the intensity and harmony of an experience and the emotional sphere contributes chiefly to beautiful experience, emotion need not be corralled by reason, but channeled toward the achievement of beauty. Further, Whitehead shows that philosophers who treat feelings as merely private are mistakenly taking a phase of concrescence to be the whole of experience. For Whitehead, “there is no element in the universe capable of pure privacy.”16 The impossibility of pure privacy undermines the conceptual option of positivists and others who atomize and privatize feeling in order to dismiss its role in moral experiences as subjectivism or emotivism, both of which result in relativism.

Moral experience and aesthetic experience work dialectically: “The function of morality is to promote beauty in experience,”17 but emotions inform morality by adding to the value of experience. Sensation and emotion are not passively received, private reifications; instead, they seamlessly compose the environment we inhabit. Cobb contends that “the purely aesthetic impulse and the moral one exist in a tension” and that “the good aimed at for others is an aesthetic good — the strength of beauty of their experience.”18

Whitehead writes:

In our own relatively high grade human existence, this doctrine of feelings and their subject is best illustrated by our notion of moral responsibility. The subject is responsible for being what it is in virtue of its feelings. It is also derivatively responsible for the consequences of its existence because they flow from its feelings.19

That our existence flows from our feelings reveals the foundation of moral action on aesthetic, αἰσθηματικός, “sensuous” experience. When Whitehead contends that our moral actions flow from our feelings, he places a primacy upon our emotional comportment. The main contribution we make to others is our spirit or attitude.20This spirit is a comportment and temperament, an angle of vision. If our vision is broad and seeks to contribute to the strength of beauty of others’ experience, it is continuous with moral experience. Moral vision is attitudinal and acting according to calculation, deliberation, and reason, while poor in spirit, is not moral action. Whitehead posits a theory of value where our goal is to realize a strength of beauty in our immediate occasions of action. Taking a calculating attitude towards future consequences endangers this goal.21 It is misleading to think that one can calculate rationally toward that best action.22 Rather, such moral rationalism can justify activity that we feel is inhumane, evil, ugly, unjust, and wrong. It can sever means from ends and justify that which our sentiments would impeach.

Whitehead’s speculative metaphysics, by using humanistic and aesthetic language, includes a description of moral experience. Occasions of activity become harmonious with their environment by acting in the service of beauty. Actions emanate from feelings, and right action is not the function of rational deliberation, but of whole-part relations, of fitting the variety of detail and contrast under the unity of an aesthetic concrescence. Whitehead’s is a seductive account of reality, but nowhere in it do we find something like evil. Those skeptical of such an aesthetic description of moral experience may ask, “Where is the Holocaust in this picture?” Thus, below a recourse to two films about Nazism, aesthetics, and morality enables the skeptic to reexamine the continuity between ethics and aesthetics and consider a broader, less reductive, understanding of aesthetics itself. Before addressing this question, another account of how process philosophy maintains continuity between ethics and aesthetics is in order.

John Dewey at the Intersection

In order to outline Dewey’s description of the aesthetic dimensions of moral experience, a cursory illustration of the continuity at work in his metaphysics of experience and theory of inquiry is in order. Dewey described the generic traits of human experience as both precarious and stable.23 Indeterminate situations produce the conditions of instability.24 Subjecting a precarious situation to inquiry constitutes it as problematic, enabling an agent to identify possible means of resolving the situations within the constituent features of the uniquely given situation. Our employment of imaginative intelligence directs our activity in an effort to resolve the situation by rearranging the conditions of indeterminacy toward settlement and unification.25

In a manner similar to Whitehead, Dewey refers to the creative integration of the entire complex situation with the term “value.”26 One constituent in the activity of unifying the problematic situation is the end-in-view, which functions as a specific action coordinating all other factors involved in the institution and resolution of the problem. The value is the integration and unification of the situation. When the end-in-view functions successfully toward the integration of the situation, the resultant unification is a “consummatory phase of experience.”27 Dewey wrote, “Values are naturalistically interpreted as intrinsic qualities of events in their consummatory reference.”28 Their naturalistic interpretation renders the experience of value and the process of valuation continuous with other natural processes. That is, the ends-in-view, whether or not these are moral ideals, do not exist antecedent to inquiry into the complex, historical, and uniquely given situation, as the rationalists would have it. The general traits of moral experience are found within aesthetic experience — dispelling the need dichotomize experience into the cognitive and the emotional — because values are qualities of events.

The ability to examine the aesthetic dimensions of moral experience depends on the way Dewey defines an aesthetically unified and integrated experience as consummatory. The consummation refers to the experience of the unification of meaning of all of the phases of a complex experience.29 Thus, the aesthetic experience gives a holistic meaning to the precariousness of its parts. The value of an experience, including moral value, refers, as in Whitehead’s description, to whole-part relations and the unification of various elements therein.

Art is the skill of giving each phase its meaning in light of the whole. Art unifies each function of the experience, giving reflection, action, desire, and imagination an integrated relation both to each other and to the possibility of meaningful resolution.30 Thus, Dewey refuses to parcel out a separate faculty at work in isolation in any meaningful experience, whether that is reason in cognition or emotion in sympathetic attention to a friend. The consummatory experience is one in which we employ imaginative intelligence in appropriating aesthetic, felt elements of experience above and beyond their immediacy and one in which the instability of their immediacy is seen imaginatively as a possibility toward its meaningful integration.31

Thus, artful conduct includes moral conduct, but in a way that both avoids the need to import ideals transcendent to our experience and gives moral ideals their reality in the meaning that ensues in the consequences of their enactment. The features of artful conduct inherent in moral behavior concern the ability to see possibilities in the elements of precariousness, “to see the actual in light of the possible.”32 Where the rationalist searches for a universal concept to justify a given, isolated action whose justification could be known but not felt, the moral imagination enables the agent to envision in her environment the constituent possibilities in order to reconstruct the situation.

Both Whitehead and Dewey treat moral experience as continuous with the aesthetic experience of intensity, meaning, unification, and harmony found in the consummatory phase of experience, or in Whitehead’s terms, in concrescence. Both treat vision and imagination, not calculative rationality, as operative in navigating morally problematic situations. The general trend running through these process philosophies that maintains continuity between ethics and aesthetics concerns whole-part relations. The individual in morally charged situations must harmonize her particular conduct to the whole of her environment broadly construed. She must imaginatively find the proper fit of her conduct with her greater cultural context. If she succeeds, she harmonizes her experience and the part coheres with the whole. Value, harmony, and stability ensue. Whitehead and Dewey describe our moral experience at a sufficient level of abstraction, one which could include the hosting of a dinner party or the conducting of an orchestra. Each part must cohere with the whole — harmony is the motivating ideal.

Much like Whitehead, Dewey gives us a processive account of reality which seems to cohere with personal experience; however, Dewey’s description of the pattern of inquiry has been accused of being so broad and vague that the Nazi resolution of the Jewish problem could be described according to it..33 The Germans under Hitler constituted their situation during the Great Depression as problematic. Their economy was in shambles, and their national pride was wounded. They found within their situation the constitutive elements, marginally-German, supposed conspirators and enemies of all sorts, to employ in resolving their situation. They achieved a sort of integration of their experience and a distorted sort of harmony in armament and invasion to reincorporate native Germans outside of their truncated borders. They consciously recruited aesthetic ideals and played on the national emotions of soil and blood. Thus, according to the Hitler-reductio, to condemn morally their actions with the language of Dewey or Whitehead is no easy task. The reductio causes moral philosophers to long for universality in any of its rationalist iterations.

The philosophical depiction of aesthetic experience, of which moral dimensions compose a part, is problematic if individuals acting under aesthetic norms, guided by manners and in service of harmonizing part-whole relations, engage in outright immorality or shy away from moral duty in the face of evil. This is the “British” problem because to highlight it, we must attend to the British characters in The Remains of the Day. While much has been written on the film (and the Ishiguro novel upon which it is based), about the role of class and the symbolic nature of British imperial politics, the film also serves as an excellent test case for the continuity between aesthetics and ethics.34 The setting of The Remains of the Day, the aristocratic estate of Darlington Hall in rural England, announces an aesthetic emphasis on beauty and order which persists throughout the film. Most of the action in the film occurs in the pre-war 1930s, but the film flashes forward to the post-war 1950s to show “present” character interactions. The central characters are an emotionally-repressed butler, Mr. Stevens (Anthony Hopkins), his superior and owner of the estate in the 1930s, Lord Darlington (James Fox), and his fellow caretaker of the estate, Miss Kenton (Emma Thompson). The problematic relationship between aesthetic orientation and morality comes into view by focusing on Lord Darlington’s demeanor throughout the events of the 1930s, and Mr. Stevens’s comportment to the politically and morally problematic events that unfold at Darlington Hall.

Lord Darlington had a friend in Germany against whom he fought in the First World War, with whom he intended to sit down and have a drink after the war. But this never happened, as the German friend, ruined by the inflation that ensued in the post-Versailles Weimar Republic, took his own life. Lord Darlington exclaims to Mr. Stevens, “The Versailles Treaty made a liar out of me.” Darlington laments that the conditions of the treaty, (debt reparations, guilt clause) were too harsh: “Not how you treat a defeated foe,” as Darlington puts it. With this as his proximate motivation, Lord Darlington uses his influence to broker the policy of appeasementtoward Nazi Germany. It appears that Lord Darlington puts manners before moral duty. He hosts the delegates from Germany, France, and the United States at his home, and they dine dressed in black tie, served by the army of under-butlers commanded by Mr. Stevens.

One is tempted to view Lord Darlington’s behavior as kind, if not for other telling incidents. He temporarily agrees to employ two Jewish refugees at his estate, and it is made clear to the viewer that he understands the dangers they faced in Germany and that his home is serving as a sanctuary. However, after reading the work of Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Lord Darlington orders that two German, Jewish maids should be discharged, as he considers their employment inappropriate for his German guests. Mr. Stevens carries out the order without reflection, while Miss Kenton threatens to resign in protest, but fails to follow through out of self-admitted weakness.35 Thus, Darlington knew of the Nazi policies in Germany, understood the potential plight of the maids, but fired them anyway in service of behavior “appropriate” for his German guests.

Darlington’s elevation of manners above duty reappears as he cannot even tell his godson (Hugh Grant), whose father has died and who is soon to be married, about the birds and the bees. He asks Mr. Stevens, his butler, to do it for him. Darlington seems unwilling to confront the issue of sexuality as it offends his Victorian manners and sensibilities. Thus, manners, while they can be seen as the outward display of inner character, here get in the way of the more difficult, unmannerly, and inappropriate conduct commanded in the face of negotiation with the Germans, the employment of the Jewish maids, and the acceptance of surrogate fatherly duties.

Mr. Stevens’s motivations are more opaque to the audience. He is so univocally driven to serve and fulfill his duty to Lord Darlington, that he almost fails to portray any moral subjectivity.36 But as the head butler, his service is also for the aesthetic ideals of orderliness and cleanliness. The prospect of a dustpan being left on the landing frightens him, such that he rushes to retrieve it before his employer notices his shortcoming. Mr. Stevens’s single-minded focus is best displayed when his own father, also an employee, is dying. Stevens attends to the dinner of the foreign delegates without pain or pause, while his own father lies on his death bed. His relationship with Miss Kenton, central to the development of his character, reveals his coldness, emotional repression, and narrowly driven service toward aesthetic ends. Miss Kenton first extends kindness to Mr. Stevens by putting flowers in his office, but he asks that they be removed so as not to distract him. She falls in love with Mr. Stevens and ends up in tears when she tries to break through his emotional wall and communicate her love to him. But he ignores her and asks to be excused to attend to his duties. Before her eventual departure and engagement to another man, she insults Stevens out of manifest distress that he has never expressed any emotional interest in her, but he still remains unmoved. After his reunion with her in the 1950s, Stevens departs for Darlington Hall in a deluge of rain. Kenton cries, but Stevens, still fails to demonstrate any feeling and only raises his hat out of politeness. While Stevens’s class-based subordination could explain his failure to fulfill his duty to his father, his coldness to Miss Kenton illustrates that he was a cold rationalist in service of aesthetics — thinly defined aesthetics.

Reflecting on Mr. Stevens’s relationship to Miss Kenton reveals two sides of the problem at the intersection of aesthetics and ethics. First, because he serves only the aesthetic ideals of order, beauty, and cleanliness, he does a disservice to the human and intersubjective dimensions of moral experience. He is polite but inattentive and stoic in the face of obvious human suffering, from the firing of the Jewish maids, to the death of his father, to the jilted and regretful Miss Kenton. Does this pose a problem for the continuity between aesthetics and ethics? Stevens serves beauty at the cost of moral duty but also interpersonal sympathy. Since an emotional angle of vision is the necessary condition for attending to moral circumstances, his aesthetic orientation is too narrow. While he has an aesthetic ideal as his motive, he has a rational methodology to achieve it. He acts in each situation as if subsuming his particular action under the universal conceptual criteria of serving beauty and order. He does not allow his actions to flow from his feelings as Whitehead would prescribe. His contribution to others is his spirit, but this is a cold, deliberate, and rational spirit. Thus, with Mr. Stevens as a test case, a conception of aesthetic experience needs to be broad enough to include emotional comportment. Failing to do so through operating in service of a narrow ideal of beauty reveals an impoverished sense of aesthetics which results in immorality.

American Congressman, Mr. Lewis (Christopher Reeve) of The Remains of the Dayserves as a pivot to the American problem at the intersection of aesthetics and ethics discussed at length below. Laughed at as nouveau riche by the British delegates, Lewis attends the conference with the intent of resisting the policy of appeasement. Because he fails to recruit the French delegate, Dupont d’Ivry (Michael Lonsdale), to his side (D’Ivry is busy attending to his sore feet), Mr. Lewis resorts to making an impolite toast at the black tie dinner. He argues in favor of the Realpolitik of professionals, rather than that of “honorable amateurs,” which is his epithet for the noblemen in his company and the Lord who is his host. In his toast “to the professionals” he embodies the moral high ground against the Nazis and the unmannerly and barefooted behavior of a stereotypical American on aristocratic soil; thus he hammers in the wedge that separates manners from morals. Apparently, Americans stand up for right against wrong even at the expense of politeness and pretty conduct. Lewis is a representative character for those skeptical of continuity between aesthetics and ethics. He knows that aesthetic ideals, when reducible to the appreciation of good taste and mannerly behavior, can dull moral distinctions. Yet he fails to unify the precariousness of his situation in a manner which Whitehead or Dewey describe.

The American Problem at the Intersection: Taking Sides

Taking Sides tells the story of Dr. Wilhelm Furtwängler, (Stellan Skarsgård), one of the most respected German conductors of the 20th century, who chose to remain in Germany during the Nazi regime. After Germany’s defeat, he fell victim to a ruthless investigation by the Allies. The major in charge of the investigation is a stereotypically uncultured American, Major Steven Arnold (Harvey Keitel), who works in the insurance business. Arnold tries to uncover how complicit Furtwängler was. Furtwängler was appointed to the Privy Council, he was Hitler’s favorite conductor, and Goebbels and Goering honored him. However, he never joined the Nazi party, he helped numerous Jews escape, and several witnesses testify that he tried to protect Jewish musicians under his direction.

The audience is left to judge Furtwängler morally. On the one hand, Arnold has the moral high ground. The Nazis perpetrated the Holocaust, and the Allied victory ended it. Justice awaits the guilty. But Major Arnold is no Congressman Lewis, who has the outward appearance of a British Peer but falls short of their mannerly conduct only by degree. Arnold is a bullying interrogator, somewhere between the caricature of an ugly American and a down-to-earth pragmatist who thinks musical genius is no excuse for collusion with Nazism, and he is willing to employ an overbearing rudeness to expose this. For Arnold, the question is all about strength of will, and he deems Furtwängler weak. However, Arnold seems to misunderstand most of Furtwängler’s replies to his questions, and at times, his interrogation seems like self-righteous taunting and badgering. The viewer is left wondering whether the distressed conductor or the clinched-fist interrogator is acting more like a Nazi.

In one telling exchange, Furtwängler claims that art has mystical powers, which nurture man’s spiritual needs. He confesses to being extremely naïve. While having maintained the absolute separation of art and politics, he devoted his life to music because he thought through music he could do something practical: to maintain liberty, humanity, and justice. Arnold replies with sarcastic disdain, “Gee, that’s a thing of beauty. […] But you used the word “naïve.” Are you saying you were wrong in maintaining the separation of art and politics?”37 Furtwängler replies that he believed art and politics should be separated, but that they were not kept separate by the Nazis, and he learned this at his own cost. Furtwängler is in an obvious bind here. He cannot hold the following propositions together without internal contradiction: (1) Art has mystical power which nurture’s man’s spiritual needs; (2) Art and politics should be kept separate; (3) Art can maintain liberty, justice and humanity; (4) Art was not kept separate from politics during Nazi rule in Germany, and this was a bad thing. If art nurtures man’s spiritual needs, but art must be kept separate from politics, are man’s spiritual needs distinct from questions of community and well-functioning societies? Put otherwise, can music perform its practical function of maintaining justice, while being separate from politics? It would not seem so.

In what follows this interrogation, Arnold accuses Furtwängler of weakness, of selling out to the Nazis for ordinary petty reasons of fear, jealousy of other conductors, and selfishness. Arnold’s two subordinates are offended by his demeanor and his denigration of a national artistic genius and hero. His assistant eventually refuses to participate. She claims that Arnold is embodying the demeanor of the S.S., which she witnessed firsthand. But Arnold shows her a film of corpses being bulldozed into mass graves, and he tells her that Furtwängler’s friends did this, and by virtue of the fact that Furtwängler actually helped some Jews escape, he knew what they were doing.

The moment of supposed revelation for the viewers of the film comes by way of archival footage, in which Furtwängler is shown shaking hands with Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels after a concert. Furtwängler’s face reveals the complexity of emotions at work — placidness, fear, and contempt. Furtwängler wipes his hand on his leg, revealing his disdain for his patron, but remains reserved and inoffensive. At once the viewer feels he is redeemed, because his true feelings for Goebbels and the Nazi project are revealed, but Furtwängler’s weakness is evident, as Arnold would have pointed out. Ultimately Furtwängler served the harmonious sensibility of artistic creation. Indeed, throughout the film the German admiration of him is severe, especially when contrasted to Arnold’s unimpressed frankness with him. The German temperament and faithfulness to aesthetic appreciation is manifest in a scene where the German audience stands in the rain, listening to Furtwängler conduct a symphony. To leave would offend, and service to the aesthetic ideals cannot give way to pragmatic considerations — how “American” that would be! One imagines Arnold thinking “what insensible dolt stands in the rain to listen to music?” Perhaps Congressman Lewis’s willingness to offend at the black tie dinner can be seen as a middle ground between Arnold’s bullying and Furtwängler’s and Darlington’s inverted values. However, this might only translate conduct into class, hiding the one true moral question beneath another layer of social convention. Arnold would insist that knowing where your salad fork belongs may not prevent you from colluding with murderers.

The Continuity between Ethics and Aesthetics

For both Whitehead and Dewey there are no universal moral situations. Our occasions of experience are always contextual and specific, never occurring in vacuous actuality. But this calls for a more general approach to descriptive ethics, not a more particularized prescription of universal moral laws. Both philosophers begin with a description of the general traits of experience and each uses highly aesthetic language. Each treats imagination and vision, not rationality, as operative in navigating morally problematic situations. Whitehead, by making feeling a metaphysical category, gives emotion a primary role; Dewey, in collapsing the gap between scientific, practical, and moral inquiries, gives imaginative intelligence primacy.

Neither of our two films presents the ideal character, with an emotional comportment and an intensity of experience able to serve as the causally efficacious and morally demanding superject in its environment. Nor do they offer a character of superior imaginative intelligence who finds and applies the elements of her problematic situation as means toward the valuable integration of meaning. This is not a surprise. England appeased the Nazis; the Holocaust occurred and so did the very limited prosecution of the guilty by the Allies afterwards. Furthermore, ugly, but welcomed, Americans plodded onto European soil either on the model of Major Arnold, at worst, or on that of Congressman Lewis at best. (He eventually buys Darlington Hall and retains Mr. Stevens as his butler, but he installs a ping-pong table there, of all aesthetic affronts). Does the “American” problem recur in summer retreats to European museums and cafes? Americans plod, loud and entitled, over the artistic feats of the Continent, and their European hosts translate aesthetic missteps into moral offense.

Where did each character fall short, and what did their shortcomings reveal about the intersection of aesthetics and ethics? Lord Darlington employed his servants to erect a mannerly and orderly veneer between him and that which is ugly. However, he can be viewed as a tragic figure because his mild manners and sensitivity to common cultural (and aesthetic in the narrow sense) values with the Germans were used against him. He ended in disgrace as the news of his involvement in the appeasement was publicized by the press. But his heightened sense of manners disabled him from confronting the soil of moral problems as he did not want to get dirty — (that’s what the servants are for). The head butler, Stevens, was not the emotionally comported or spontaneously active character tacitly advocated for by Whiteheadian ethics, but the coldly rational and deliberative agent serving a narrow aesthetic end. Miss Kenton and Furtwängler demonstrated a weakness of will in the face of wrong-doing, and for that they are condemned, not by an aesthetic measure, but by a pragmatic one. Their beliefs were their propensities to act, and their inability to act revealed a weak belief in their moral ideals.38 But the American characters are not morally pure. As the victors, the

tools they had at their disposal to resolve their situations were ready at hand, and they too were constituted by their prehensions of their environment. Denigrating an artistic genius does not show the service of a moral ideal, but only the privileged position of Major Arnold of judging Furtwängler’s weakness from outside his context.

These films do illustrate the tension at work at the intersection of aesthetics and ethics. While both films depict the limitations and failures of the tendency to “aestheticize” morality, they do not prove the need to import a falsely universal moral ideal antecedent to the experience of a particular problematic situation in order to judge right from wrong. Insofar as the tools needed to make these judgments are had in experience, they have been, accurately described by figures like Whitehead and Dewey, in aesthetic language. The Reductio ad Hitlerum only succeeds if the meaning of aesthetics is deflated and reduced to something much narrower than either Whitehead or Dewey intended, such as reflection on artistic creation. The broad use of aesthetics advocated here does not fail to draw moral distinctions in the face of Nazi atrocities while blindly serving the ideal of artistic beauty or mere manners. Rather, as including imagination and emotion, an aesthetic orientation to ethics encompasses the problems posed by the characters’ shortcomings, even if their moral shortcomings run parallel to their heightened aesthetic and misguided sensibilities.

- Hans Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method, (London: Continuum, 2006), 31. Nöel Carroll makes the further claim that because of Kant’s aesthetic theory and its interpretation, twentieth century philosophers have neglected the ethical criticism of art. (Noël Carroll, “Art and Ethical Criticism: An Overview of Recent Directions of Research,” Ethics, Vol. 110, No. 2 (January 2000), pp 350). ↩︎

- Thomas Alexander, “John Dewey and the Moral Imagination: Beyond Putnam and Rorty toward a Postmodern Ethics,” Transactions of the Charles Sanders Peirce Society, Vol. XXIX, No. 3, (Summer 1993), 373. ↩︎

- For a complex examination of this problematic, see George Kateb, “Aestheticism and Morality: Their Cooperation and Hostility,” Political Theory, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Feb., 2000), pp. 5-37. ↩︎

- See Noël Carroll, “Art and Ethical Criticism: An Overview of Recent Directions of Research,” Ethics, Vol. 110, No. 2 (January 2000), pp. 350-387. Carroll highlights the problematic relationship between ethics and art criticism by examining the immorality and aesthetic value of The Triumph of the Will, among other artifacts. ↩︎

- Boaz Neumann, “The National Socialist Politics of Life,” New German Critique, No. 85, Special Issue on Intellectuals (Winter, 2002), p 120. ↩︎

- Paul Betts, “The New Fascination with Fascism: The Case of Nazi Modernism,” Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 37, No. 4 (Oct., 2002), 546. ↩︎

- Betts, “The New Fascination with Fascism,” 547. ↩︎

- Betts, “The New Fascination with Fascism,” 547. ↩︎

- Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, (London: The Free Press, 1978), 18. ↩︎

- Whitehead, Process and Reality, 18, 22. ↩︎

- Whitehead, Process and Reality, 19. ↩︎

- Harold B. Dunkel, “Creativity and Education,” Educational Theory, Volume XI, Number 4, (1961), 209. ↩︎

- Whitehead, Process and Reality, 29. ↩︎

- John B. Cobb, “Whitehead’s Theory of Value,” religion-online.org Accessed 2/27/2015. ↩︎

- Cobb, “Whitehead’s Theory of Value.” ↩︎

- Whitehead, Process and Reality, 212. ↩︎

- Cobb, “Whitehead’s Theory of Value.” ↩︎

- Cobb, “Whitehead’s Theory of Value.” ↩︎

- Process and Reality, 222. ↩︎

- Cobb, “Whitehead’s Theory of Value.” ↩︎

- Cobb, “Whitehead’s Theory of Value.” ↩︎

- Cobb, “Whitehead’s Theory of Value.” ↩︎

- Dewey, Later Works Vol. 1, Ed. Boydston, (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1967-1990) 42-45. ↩︎

- Dewey, Logic The Theory of Inquiry, LW 12: 110. ↩︎

- Dewey, LW 12: 121. ↩︎

- James Gouinlock, John Dewey’s Philosophy of Value, (New York: Humanities Press, 1972), 132. ↩︎

- Dewey, LW 10: 143. ↩︎

- Dewey, LW 1: 9. ↩︎

- Gouinlock, John Dewey’s Philosophy of Value, 150. ↩︎

- Gouinlock, John Dewey’s Philosophy of Value, 151. ↩︎

- Gouinlock, John Dewey’s Philosophy of Value, 152. ↩︎

- Alexander, “John Dewey and the Moral Imagination,” 384. ↩︎

- Richard Posner*, Law, Pragmatism, and Democracy*, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003), p. 45. Posner claims that pragmatism, via Darwinism, has nurtured philosophies including Nazism. ↩︎

- See, for example, Meera Tamaya, “Ishiguro’s Remains of the Day: The Empire Strikes Back,” Modern Language Studies, Vol. 22, No. 2 (spring, 1992), pp. 45-56. Tanaya focuses on the relationship between Darlington and Stevens as one of colonizer and colonized, subject and object. ↩︎

- See Geoffrey G. Field, Evangelist of Race: The Germanic Vision of Houston Stewart Chamberlain, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1981). ↩︎

- See McCombe, “The End of (Anthony) Eden: Ishiguro’s “The Remains of the Day” and Midcentury Anglo-American Tensions,” 78. ↩︎

- See Page R. Laws, “Taking Sides by Ronald Harwood; India Ink by Tom Stoppard,” (review), Theatre Journal, Vol. 48, No. 1 (Mar., 1996), pp. 107-108. Laws makes note of the fact that the Nazis used art in the service of politics. ↩︎

- Charles Sanders Peirce, Collected Papers (1958-1966), Vol. 5, Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss, eds., (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press), 400. ↩︎

References:

Alexander, Thomas. “John Dewey and the Moral Imagination: Beyond Putnam and Rorty toward a Postmodern Ethics.” Transactions of the Charles Sanders Peirce Society. Vol. XXIX. No. 3. (Summer 1993).

Betts, Paul. “The New Fascination with Fascism: The Case of Nazi Modernism.” Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 37. No. 4. (Oct., 2002).

Carroll, Noël. “Art and Ethical Criticism: An Overview of Recent Directions of Research.” Ethics. Vol. 110, No. 2 (January 2000), pp. 350-387.

Cobb, John B. Jr. “Whitehead’s Theory of Value.” www.religion-online.org.

Dewey, John. Later Works Vol. 1, Ed. Boydston, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1967-1990.

Dewey, John. Later Works Vol. 10. Ed. Boydston, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1967-1990.

Dewey, John. Later Works Vol. 12. Ed. Boydston. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1967-1990.

Dunkel, Harold B. “Creativity and Education,” Educational Theory. Vol. XI. No. 4. (1961).

Field, Geoffrey G. Evangelist of Race: The Germanic Vision of Houston Stewart Chamberlain. New York: Columbia University Press, 1981.

Gadamer, Hans Georg. Truth and Method. London: Continuum, 2006.

Gouinlock, James. John Dewey’s Philosophy of Value. New York: Humanities Press, 1972.

Ivory, James. The Remains of the Day. Merchant Ivory Film, 1993.

Kateb, George. “Aestheticism and Morality: Their Cooperation and Hostility.” Political Theory. Vol. 28. No. 1 (Feb., 2000), pp. 5-37.

Neumann, Boaz. “The National Socialist Politics of Life.” New German Critique. No. 85. Special Issue on Intellectuals (Winter, 2002), pp. 107-130.

Peirce, Charles Sanders, (1958-1966) Collected papers. Vols. 1- 6, Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss, eds., (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press).

Posner, Richard. Law, Pragmatism, and Democracy, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003.

Szabó, István. Taking Sides. Paladin Production S.A., 2001.

Whitehead, Alfred North. Process and Reality. London: The Free Press, 1978.About the Author:

Seth Vannatta earned his PhD in philosophy at Southern Illinois University Carbondale and is currently an Associate Professor in the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies at Morgan State University, where he won the university award for research and scholarship in 2012. He studies the history of philosophy and American philosophy and is interested in philosophy’s relationship to other dimensions of culture including law, politics, education, and sport. He is the author of Conservationsim and Pragmatism in Law, Politics, and Ethics(Palgrave Macmillan, 2014) and editor and contributor to Chuck Klosterman and Philosophy: The Real and the Cereal (Open Court, 2012). He has published articles in The Pluralist, Contemporary Pragmatism, The European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy, Education and Culture, and others.