Five Types of Systems Philosophy

Key Terms

- Systems

- Systems Theory

- Systems Philosophy

- Systems Thinking

- Systems Dynamics

- Systems Management

- Systems Engineering

- General Systems Theory

- Cybernetics

- Complex Systems

- Agent Based Modeling

- Operations Research

- Supply Chain Management

- Money Flows

- Systems Biology

- Autopoiesis

- Autocatalysis

- Relational Science

- Relational Biology

- Networks

- Hierarchy Theory

- Process Philosophy

- Social Systems Theory

- Socio-Cybernetics

- Relational Sociology

- Hierarchical Planning

- Organizational Learning

- Second Order Cybernetics

- Third Order Cybernetics

- Holons

- Holarchy

- Heterarchy

- Global Value Chains

- Stock Flow Consistent Modeling

- Boundaries

- Economic Cycles

- Monetary Circuits

- Balance Sheets Economics

- Input Output Analysis

- Feedbacks

- Increasing Returns

- Path Dependence

- Circular Economy

- Semiotics

- Meaning

- System Sciences

- Engineered Systems

- Modularity

- Design Thinking

- Credit Chains

- Co-Evolution

- Monism

- Non Duality

- Duality

- Deep Ecology

- Society for General Systems Research in 1954

- International Society for the Systems Sciences (ISSS) in 1988

- American Society for Cybernetics

Key Scholars

- Ervin Laszlo

- Norbert Wiener

- Ludwig von Bertalanffy

- George J. Klir

- Howard Pattee

- Jay Forrester

- George Richardson

- Fritjof Capra

- James Grier Miller

- Gregory Bateson

- Niklas Luhmann

- Heinz von Foerster

- Archie J. Bahm

- Kenneth Boulding

- W. Ross Ashby

- C. W. Churchman

- Mario Bunge

- Herbert A. Simon

- Robert Rosen

- Stafford Beer

- Anatol Rapoport

- Ralph Gerard

- Russell Ackoff

- Erich Jantsch

- Ralph Abraham

- Stuart Kauffman

- Louis Kauffman

- Humberto Maturana

- Alfred North Whitehead

- Paul A. Weiss

- Kurt Lewin

- Roy R. Grinker

- William Gray

- Nicolas Rizzo

- Karl Menninger

- Silvano Arieti

- Peter Senge

FIVE TYPES OF SYSTEMS PHILOSOPHY

Source: FIVE TYPES OF SYSTEMS PHILOSOPHY

- Atomism

- Holism

- Emergentism

- Structuralism

- Organicism

Source: FIVE TYPES OF SYSTEMS PHILOSOPHY

Bunge’s three types of systems philosophies are expanded to five: atomism (the world is an aggregate of elements, without wholes; to be understood by analysis), holism (ultimate reality is a whole without parts, except as illusory manifestations; apprehended intuitively), emergentism (parts exist together and their relations, connections, and organized interaction constitute wholes that continue to depend upon them for their existence and nature; understood first analytically and then synthetically), structuralism (the universe is a whole within which all systems and their processes exist as depending parts; understanding can be aided by creative deduction), and organicism (every existing system has both parts and whole, and is part of a larger whole, etc.; understanding the nature of whole-part polarities is a clue to understanding the nature of systems. How these five types correlated with theories of conceptual systems and methodologies is also sketched.

Source: Five systems concepts of society

Bunge’s three “concepts of society” exemplify three types of systems philosophy. This article criticizes Bunge’s analysis as minimally inadequate by expanding his range to five concepts of society which exemplify five kinds of systems philosophy: individualism, emergentism, organicism, structuralism, and holism. Emphasis is given to stages in the development of emergentism, including cybernetics (four stages), systems theory (eight stages), and holonism, and then to opposing structuralism (four examples). Organicism as a type of systems philosophy and concept of society is constructed by incorporating the constructive claims of both emergentism and structuralism and by overcoming oppositions to them systematically.

Source: Holons: Three conceptions

Recent advances in systems theory have required a new term, ‘holon’ (a whole of parts functioning as part of a larger whole). These advances are complicated by differing interpretations provided by three competing kinds of general systems theory: Emergentism, structuralism and organicism. For emergentism, use of the term signifies a shift in emphasis from focusing on the dynamic equilibrium between a whole and its parts to that between the whole and the larger whole of which it is a part. For structuralism, the term serves in explaining subsystem adaptation to environmental and hierarchical constraints and determinations by invariant principles. By incorporating ideas from both emergentism and structuralism into its more intricate interpretations, the author claims that organicism presents a more adequate conception of the nature of holons—now regarded as essential to general systems thinking.

Source: Comparing civilizations as systems

Comparison of Western, Indian and Chinese civilizations as cultural systems exhibiting persisting ideals constituting important structural differences reveals that two taproots of Western civilization (the Hebraic stressing will and the Greek stressing reason) as characteristics essential to the nature of the world and man, are opposed in Hindu culture idealizing Nirguna Brahman as complete absence of both will (desire) and reason (distinctions) and yogic endeavor designed to eliminate both from persons, are partially integrated as complementary opposites in Chinese taoistic yin-yang ideals about both the universe and man. Opportunities for further research comparing cultural systems seem unlimited.

Source: Systemism: the alternative to individualism and holism

Systems Philosophy

Source: Systems Philosophy

Source: Systems Philosophy

Source: Systems Philosophy

Source: Systems Philosophy

Source: Systems Philosophy

Source: Systems Philosophy

Source: Systems Philosophy

Source: Systems Philosophy

Source: Introduction to Systems Philosophy

First Published in 1972, Introduction to Systems Philosophy presents Ervin Laszlo’s first comprehensive volume on the subject. It argues for a systematic and constructive inquiry into natural phenomenon on the assumption of general order in nature. Laszlo says systems philosophy reintegrates the concept of enduring universals with transient processes within a non-bifurcated, hierarchically differentiated realm of invariant systems, as the ultimate actualities of self-structuring nature. He brings themes like the promise of systems philosophy; theory of natural systems; empirical interpretations of physical, biological, and social systems; frameworks for philosophy of mind, philosophy of nature, ontology, epistemology, metaphysics and normative ethics, to showcase the timeliness and necessity of a return from analytic to synthetic philosophy. This book is an essential read for any scholar and researcher of philosophy, philosophy of science and systems theory.

Source: General Systems Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications

Source: General Systems Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications

Source: General Systems Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications

Source: Systems Theory as the Foundation for Understanding Systems

Source: Systems Theory as the Foundation for Understanding Systems

Source: Systems Theory as the Foundation for Understanding Systems

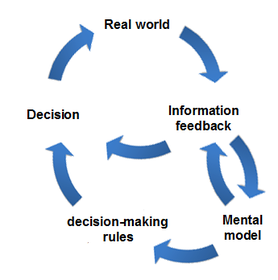

Source: Feedback Thought in Social Science and Systems Theory

My Related Posts

Systems and Organizational Cybernetics

Society as Communication: Social Systems Theory of Niklas Luhmann

From Systems to Complex Systems

Cybernetics, Autopoiesis, and Social Systems Theory

Systems Biology: Biological Networks, Network Motifs, Switches and Oscillators

Jay W. Forrester and System Dynamics

System Archetypes: Stories that Repeat

Systems View of Life: A Synthesis by Fritjof Capra

Phillips Machine: Hydraulic Flows and Macroeconomics

Cybernetics Group: A Brief History of American Cybernetics

Second Order Cybernetics of Heinz Von Foerster

Third and Higher Order Cybernetics

Ratio Club: A Brief History of British Cyberneticians

Socio-Cybernetics and Constructivist Approaches

Profiles in Operations Research

History of Operations Research

Hierarchy Theory in Biology, Ecology and Evolution

Hierarchical Planning: Integration of Strategy, Planning, Scheduling, and Execution

Gantt Chart Simulation for Stock Flow Consistent Production Schedules

Production and Distribution Planning : Strategic, Global, and Integrated

Single, Double, and Triple Loop Organizational Learning

Accounting for Global Value Chains/Global Supply Chains

Stock Flow Consistent Models for Ecological Economics

Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, Circular and Cumulative Causation in Economics

Feedback Thought in Economics and Finance

Increasing Returns and Path Dependence in Economics

Wassily Leontief and Input Output Analysis in Economics

Long Wave Economic Cycles Theory

Stock Flow Consistent Input Output Models (SFCIO)

Milankovitch Cycles: Astronomical Theory of Climate Change and Ice Ages

Micro Motives, Macro Behavior: Agent Based Modeling in Economics

Stock-Flow Consistent Modeling

Contagion in Financial (Balance sheets) Networks

Oscillations and Amplifications in Demand-Supply Network Chains

Classical roots of Interdependence in Economics

George Dantzig and History of Linear Programming

Morris Copeland and Flow of Funds accounts

Understanding Global Value Chains – G20/OECD/WB Initiative

Quantitative Models for Closed Loop Supply Chain and Reverse Logistics

Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Recursive Vision of Gregory Bateson

Paradoxes, Contradictions, and Dialectics in Organizations

Key Sources of Research

Organicism: The Philosophy of Interdependence

Archie J. Bahm

International Philosophical Quarterly

Volume 7, Issue 2, June 1967

Pages 251-284

https://doi.org/10.5840/ipq19677251

Comparing civilizations as systems.

Bahm, A.J. (1988),

Syst. Res., 5: 35-47. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.3850050105

“Organic unity and emergence.”

Bahm, Archie J.

Emergence: Complexity and Organization 14, no. 2 (2012): 116+. Gale Academic OneFile (accessed April 24, 2023). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A299258807/AONE?u=anon~a582c343&sid=googleScholar&xid=031287de.

The nature of existing systems.

Bahm, A.J. (1986),

Syst. Res., 3: 177-184. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.3850030307

Five systems concepts of society.

Bahm, A.J. (1983),

Syst. Res., 28: 204-218. https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830280304

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/bs.3830280304

FIVE TYPES OF SYSTEMS PHILOSOPHY,

ARCHIE J. BAHM (1981)

International Journal of General Systems, 6:4, 233-237, DOI: 10.1080/03081078108934801

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03081078108934801

Holons: Three conceptions.

Bahm, A.J. (1984),

Syst. Res., 1: 145-150. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.3850010207

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/sres.3850010207

SYSTEMS THEORY AND THE PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE

Rob de Vries

https://www.academia.edu/45044397/SYSTEMS_THEORY_AND_THE_PHILOSOPHY_OF_SCIENCE

Introduction to Systems Philosophy

Toward a New Paradigm of Contemporary Thought

By Ervin Laszlo

Copyright 1972

ISBN 9781032071428

352 Pages

Published September 30, 2021 by Routledge

“General systems theory: origin and hallmarks”,

Skyttner, L. (1996),

Kybernetes, Vol. 25 No. 6, pp. 16-22. https://doi.org/10.1108/03684929610126283

General Systems Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications.

Bertalanffy,L.1968.

New York: George Braziller.

(New York: Braziler, 1972 revised edition, 280p.).

The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design.

Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

General Systems Theory: Its Present and Potential.

Rousseau, D (2015),

Syst. Res., 32, 522– 533. doi: 10.1002/sres.2354.

General Systems Theory: Its Past and Potential.

Caws, P (2015),

Syst. Res., 32, 514– 521. doi: 10.1002/sres.2353.

Systems Philosophy and the Unity of Knowledge.

Rousseau, D. (2014),

Syst. Res., 31: 146-159. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2189

The science of synthesis : exploring the social implications of general systems theory

Debora Hammond.

2003 University Press of Colorado

THE MEANING OF GENERAL SYSTEM THEORY

The Quest for a General System Theory

Ludwig von Bertalanffy

Chapter 2 from General System Theory. Foundations, Development, Applications Ludwig von Bertalanffy

New York: George Braziller 1968

pp. 30-53

TRENDS IN GENERAL SYSTEM THEORY

George J. Klir, Ed

Wiley-Interscience, N.Y ., 1972, 462 pp.

Introduction to System Theory

by Niklas Luhmann, Peter Gilgen (Trans.)

Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012, pbk. (ISBN: 978-0745645728), 300pp.

GENERAL SYSTEMS THEORY

Anatol Rapoport

University of Toronto, Canada

SYSTEMS SCIENCE AND CYBERNETICS – Vol. I – General Systems Theory – Anatol Rapoport

Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS)

Systems Theories:

Their Origins, Foundations, and Development

By

Alexander Laszlo and Stanley Krippner

Published in:

J.S. Jordan (Ed.), Systems Theories and A Priori Aspects of Perception. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science, 1998. Ch. 3, pp. 47-74.

The Architecture of Complexity

Herbert A. Simon

Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 106, No. 6. (Dec. 12, 1962), pp. 467-482.

A Taoist Foundation of Systems Modeling and Thinking

Karl R. Lang and Jing Lydia Zhang

Department of Information and Systems Management,

HK University of Science & Technology (HKUST), Hongkong

Email: {klang, zhangjin}@ust.hk

Systems Theory

BRUCE D. FRIEDMAN AND KAREN NEUMAN ALLEN

FRAMEWORKS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE

The History and Status of General Systems Theory

LUDWIG VON BERTALANFFY

* Center for Theoretical Biology, State University of New York ot Buffalo

George J. Kiir, ed., Trends in General Systems Theory (New York: Wiley-lnterscience, 1972).

Click to access the_history_and_status_of_general_systems_theory.pdf

The Nature of Living Systems: An Exposition of the Basic Concepts in General Systems Theory.

Miler,James G.

World Systems Theory

by Carlos A. Martínez-Vela

An Outline of General System Theory (1950)

Ludwig von Bertalanffy

The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, Vol. 1, No. 2 (Aug., 1950), pp. 134-165

Click to access Bertalanffy1950-GST_Outline_SELECT.pdf

On the Philosophical Ontology for a General System Theory

CUI Weicheng

Key Laboratory of Coastal Environment and Resources of Zhejiang Province (KLaCER) School of Engineering, Westlake University, Hangzhou, China

Philosophy Study, June 2021, Vol. 11, No. 6, 443-458

doi: 10.17265/2159-5313/2021.06.002

Systems Theory as the Foundation for Understanding Systems

Kevin MacG. Adams

Peggy T. Hester

Joseph M. Bradley

Thomas J. Meyers

Charles B. Keating

Old Dominion University

Systems Engineering, 17(1), 112-123. 2014

doi:10.1002/sys.21255

A Brief Review of Systems Theories and Their Managerial Applications.

Cristina Mele, Jacqueline Pels, Francesco Polese, (2010)

Service Science 2(1-2):126-135. https://doi.org/10.1287/serv.2.1_2.126

https://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/pdf/10.1287/serv.2.1_2.126

Systems Philosophy

Ervin Laszlo

https://www.utpjournals.press/doi/pdf/10.3138/uram.1.3.223

Systems Philosophy

Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Systems_philosophy

- Centre for Systems Philosophy, UK

- Centre for Systems Studies, University of Hull, UK

- Club of Budapest, Hungary

- Bertalanffy Center for the Study of Systems Science

- http://www.bcsss.org/

Systems Theory

Rudolf Stichweh

Systems Philosophy and Cybernetics

Nagib Callaos

Founding President of the International Institute of Informatics and Systemics (IIIS)

SYSTEMICS, CYBERNETICS AND INFORMATICS VOLUME 19 – NUMBER 4 – YEAR 2021

Systems Philosophy: An Integral Theory of Everything?.

Pretel-Wilson, Manel. (2017).

10.13140/RG.2.2.25388.16003.

Feedback Thought in Social Science and Systems Theory

by George P. Richardson (Author)

Publisher : Pegasus Communications (January 1, 1999)

Language : English

Paperback : 374 pages

ISBN-10 : 1883823463

ISBN-13 : 978-1883823467

“Semiotic systems”

BUNGE, MARIO.

In Systems: New Paradigms for the Human Sciences edited by Gabriel Altmann and Walter A. Koch, 337-349. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter, 1998. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110801194.337

Mario Bunge: A Centenary Festschrift

Michael R. Matthews

Springer International Publishing, Aug 1, 2019 – 827 pages

Systemism: the alternative to individualism and holism

Mario Bunge

The Journal of Socio-Economics

Volume 29, Issue 2, 2000, Pages 147-157

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-5357(00)00058-5

https://philpapers.org/rec/BUNSTA

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1053535700000585

On Mario Bunge’s Definition of System and System Boundary.

Cavallo, A.M.

Sci & Educ 21, 1595–1599 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-011-9365-0

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11191-011-9365-0

A systems concept of society: Beyond individualism and holism.

Bunge, Mario (1979).

Theory and Decision 10 (1-4):13-30.

DOI 10.1007/bf00126329

https://philpapers.org/rec/BUNASC

Emergence and Evidence: A Close Look at Bunge’s Philosophy of Medicine

Rainer J. Klement 1,* and Prasanta S. Bandyopadhyay 2

1Department of Radiation Oncology, Leopoldina Hospital Schweinfurt, Robert-Koch-Straße 10, 97422 Schweinfurt, Germany

2 Department of History & Philosophy, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT, 59717, USA

* Correspondence: rainer_klement@gmx.de; Tel.: +49-9721-7202761

http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/17047/

Official URL: https://www.mdpi.com/2409-9287/4/3/50

Causality and Modern Science

Fourth Revised Edition

by Bunge, Mario (2008) Paperback

SYSTEM BOUNDARy

MARIO BUNGE (1992)

International Journal of General Systems, 20:3, 215-219, DOI: 10.1080/03081079208945031

A CRITICAL NOTE ON BUNGE’S ‘SYSTEM BOUNDARY’ AND A NEW PROPOSAL

JEAN-PIERRE MARQUIS (1996)

International Journal of General Systems, 24:3, 245-255, DOI: 10.1080/03081079608945120

Correspondence: Systems profile.

Bahm, A.J. (1987),

Syst. Res., 4: 203-209. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.3850040306

References

- S. Alexander, Space, Time and Deity. Macmillan, New York (1923).

- A. J. Bahm, What is philosophy? Sci. Monthly 52 (1941), 533– 560.

- A.J. Bahm, Meanings of negation. Philos. Phenomenological Res. 22 (1961), 197– 184.

- A. J. Bahm, Organicism: The philosophy of interdependence. Internat. Philos. Quart. 7 (1967),251– 284.

- A. J. Bahm, Systems theory: Hocus pocus or holistic science? Gen. Syst. 14 (1969), 176– 178.

- A. J. Bahm, Polarity, Dialectic, and Organicity. Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, ILL (1970).

- A. J. Bahm, General systems theory as philosophy. Gen. Syst. Bull. 4 (1973), 4– 6.

- A. J. Bahm, Comparative Philosophy: Western, Indian and Chinese Philosophies Compared. Vikas, New Delhi, and World Books, Albuquerque (1977).

- A. J. Bahm, review of J. G. Miller’s Living Systems. Gen. Syst. Bull. 10 (1979), 31– 32.

- A. J. Bahm, The Philosopher’s World Model. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT (1979).

- A. J. Bahm, Organic logic: An introductory essay. Dialogos 40 (1982), 107– 122.

- A. J. Bahm, Five types of systems philosophy. Int. J. Gen. Syst. 6 (1981), 233– 237.

- A. J. Bahm, Five systems concepts of society. Behav. Sci. 28 (1983), 204– 218.

- A. J. Bahm, Holons: Three conceptions. Syst. Res. 1 (1984), 145– 150.

- A. J. Bahm, Wholes and parts of things. Contextos 11 (1984), 7– 26.

- A. J. Bahm, The nature of existing systems. Syst. Res. 3 (1986), 177– 184.

- B. H. Banathy (ed.), Systems Inquiring: Theory, Philosophy, Methodolgy. Intersystems Publications, Seaside, CA (1985).

- L. von Bertalanffy, General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications. George Braziller, New York (1968).

- T. D. Bowler, General Systems Thinking: Its Scope and Applicability. North-Holland, New York(1981).

- M. Bunge, A World of Systems, Vol. 4 of A Treatise on Basic Philosophy. Reidel, Dordrecht(1979).

- M. Bunge, General systems and holism. Gen. Syst. 22 (1977), 87– 90.

- M. Bunge, A systems concept of society. Theory Decision 10 (1979), 13– 30.

- C. W. Churchman, The Systems Approach. Delacorte Press, New York (1968).

- C. H. Cooley, Social Organization. Scribner’s, New York (1909).

- C. H. Cooley et al., Introductory Sociology. Scribner’s, New York (1933).

- E. A. Feigenbaum and P. McCorduck, The Fifth Generation: Artificial Intelligence and Japan’s Computer Challenge to Our World. Addison Wesley, Reading, MA (1983).

- A. Koestler, The Ghost in the Machine. Hutchinson, London (1967).

- A. Koestler, Janus: A Summing Up. Hutchinson, London (1978).

- E. Laszlo, Introduction to Systems Philosophy. Gordon & Breach, New York (1972).

- E. Laszlo, A Strategy for the Future: A Systems Approach to World Order. Braziller, New York(1974).

- E. Laszlo, Goals for Mankind: A Report to the Club of Rome on the New Horizons of the Global Community. Dutton, New York (1977).

- J. G. Miller, Living Systems. McGraw-Hill, New York (1978).

- D. L. Meadows, Limits for Growth. Potomac Associates, Washington, DC (1972).

- M. Mesarovic, Mankind at the Turning Point. Dutton, New York (1974).

- C. L. Morgan, Emergent Evolution. Williams & Norgate, London (1923).

- D. H. Parker, The Principles of Aesthetics. Silver Burdett, Boston, MA (1920).

- J. Rose (ed.), Current Topics in Cybernetics and Systems. Springer, Heidelberg (1978).

- R. W. Sellars, Evolutionary Naturalism. Macmillan, New York (1922).

- R. W. Sellars, The Principles and Problems of Philosophy. Macmillan, New York (1926).

- J. S. Stamps, Holonomy: A Human Systems Theory. Intersystems, Seaside, CA (1980).

- J. Warfield, An Assault on Complexity. Battelle Memorial Institute, Columbus, OH (1973).

- J. Warfield, Structuring Complex Systems. Battelle Memorial Institute, Columbus, OH (1974).

- A. N. Whitehead and B. Russell, Principia Mathematia, Second Edition, Vol. I. Cambridge University Press, London (1925).

- N. Wiener, Cybernetics. Wiley, New York (1949).

Further reading[edit]

- Diederik Aerts, B. D’Hooghe, R. Pinxten, and I. Wallerstein (Eds.). (2011). Worldviews, Science And Us: Interdisciplinary Perspectives On Worlds, Cultures And Society – Proceedings Of The Workshop On Worlds, Cultures And Society. World Scientific Publishing Company.

- Diederik Aerts, Leo Apostel, B. De Moor, S. Hellemans, E. Maex, H. Van Belle, and J. Van der Veken (1994). Worldviews: from fragmentation to integration. Brussels: VUB Press.

- Archie Bahm (1981). Five Types of Systems Philosophy. International Journal of General Systems, 6(4), 233–237.

- Archie Bahm (1983). Five systems concepts of society. Behavioral Science, 28(3), 204–218.

- Gregory Bateson (1979). Mind and nature : a necessary unity. New York: Dutton.

- Gregory Bateson (2000). Steps to an ecology of mind. Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Kenneth Boulding (1985). The World as a Total System. Beverly Hills, CA.: Sage Publications.

- Mario Bunge (1977). Ontology I: The furniture of the world. Reidel.

- Mario Bunge (1979). Ontology II: A World of Systems. Dordrecht: Reidel.

- Mario Bunge (2010). Matter and Mind: A Philosophical Inquiry. New York, NY: Springer.

- Francis Heylighen (2000). What is a world view? In F. Heylighen, C. Joslyn, & V. Turchin (Eds.), Principia Cybernetica Web (Principia Cybernetica, Brussels), http://cleamc11.vub.ac.be/WORLVIEW.html.

- Arthur Koestler (1967). The Ghost in the Machine. Henry Regnery Co.

- Alexander Laszlo & S. Krippner S. (1998) Systems theories: Their origins, foundations, and development. In J.S. Jordan (Ed.), Systems theories and a priori aspects of perception. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science, 1998. Ch. 3, pp. 47–74.

- Laszlo, A. (1998) Humanistic and systems sciences: The birth of a third culture. Pluriverso, 3(1), April 1998. pp. 108–121.

- Laszlo, A. & Laszlo, E. (1997) The contribution of the systems sciences to the humanities. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 14(1), April 1997. pp. 5–19.

- Ervin Laszlo (1972a). Introduction to Systems Philosophy: Toward a New Paradigm of Contemporary Thought. New York N.Y.: Gordon & Breach.

- Laszlo, E. (1972b). The Systems View of the World: The Natural Philosophy of the New Developments in the Sciences. George Braziller.

- Laszlo, E. (1973). A Systems Philosophy of Human Values. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 18(4), 250–259.

- Laszlo, E. (1996). The Systems View of the World: a Holistic Vision for our Time. Cresskill NJ: Hampton Press.

- Laszlo, E. (2005). Religion versus Science: The Conflict in Reference to Truth Value, not Cash Value. Zygon, 40(1), 57–61.

- Laszlo, E. (2006a). Science and the Reenchantment of the Cosmos: The Rise of the Integral Vision of Reality. Inner Traditions.

- Laszlo, E. (2006b). New Grounds for a Re-Union Between Science and Spirituality. World Futures: Journal of General Evolution, 62(1), 3.

- Gerald Midgley (2000) Systemic Intervention: Philosophy, Methodology, and Practice. Springer.

- Rousseau, D. (2013) Systems Philosophy and the Unity of Knowledge, forthcoming in Systems Research and Behavioral Science.

- Rousseau, D. (2011) Minds, Souls and Nature: A Systems-Philosophical Analysis of the Mind-Body Relationship. (PhD Thesis, University of Wales, Trinity Saint David, School of Theology, Religious Studies and Islamic Studies).

- Jan Smuts (1926). Holism and Evolution. New York: Macmillan Co.

- Vidal, C. (2008). Wat is een wereldbeeld? [What is a worldview?]. In H. Van Belle & J. Van der Veken (Eds.), Nieuwheid denken. De wetenschappen en het creatieve aspect van de werkelijkheid [Novel thoughts: Science and the Creative Aspect of Reality]. Acco Uitgeverij.*

- Jennifer Wilby (2005). Applying a Critical Systematic Review Process to Hierarchy Theory. Presented at the 2005 Conference of the Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology. Retrieved from https://dspace.jaist.ac.jp/dspace/handle/10119/3846

- Wilby, J. (2011). A New Framework for Viewing the Philosophy, Principles and Practice of Systems Science. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 28(5), 437–442.

External links[edit]

- Systems Philosophy and Applications: A Bibliography by W. Huitt, Valdosta, Georgia, USA, last revised December 2007.

- Organization and Process: Systems Philosophy and Whiteheadian Metaphysics by James E. Huchingson.

Adams KM, Hester PT, Bradley JM, Meyers TJ, Keating CB. 2014. Systems theory as the foundation for understanding systems. Systems Engineering 17(1): 112– 123.

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Archer MS. 2013. Social Morphogenesis. Springer: Dordrecht.

Billingham J. 2014a. GST as a route to new systemics. Presented at the 22nd European Meeting on Cybernetics and Systems Research (EMCSR 2014), 2014, Vienna, Austria. In EMCSR 2014: Civilisation at the Crossroads—Response and Responsibility of the Systems Sciences, JM Wilby, S Blachfellner, W Hofkirchner (eds.). EMCSR: Vienna, 2014; 435– 442.

Billingham J. 2014b. In search of GST. Position paper for the 17th Conversation of the International Federation for Systems Research on the subject of ‘Philosophical Foundations for the Modern Systems Movement’, St. Magdalena, Linz, Austria, 27 April – 2 May 2014. (pp. 1– 4).

Billingham J. 2015. GST* as the unifying theory of the Systems Sciences. In Systems Philosophy and Its Relevance to Systems Engineering, D Rousseau, J Wilby, J Billingham, S Blachfellner (eds.). Workshop held on 11 July 2015 at the International Symposium of the International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE) in Seattle, Washington, USA. Available at https://sites.google.com/site/syssciwg2015iw15/systems-science-workshop-at-is15

Boulding KE. 1956a. General systems theory—the skeleton of science. Management Science 2(3): 197– 208.

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Boulding KE. 1956b. The Image: Knowledge in Life and Society. University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, Mich.

Bunge M. 1973. How do realism, materialism, and dialectics fare in contemporary science? In Method, Model and Matter. Reidel: Dordrecht; 169– 185. Reproduced in M Maher (ed.), 2001, Scientific Realism, Amherst: Prometheus, pp. 27-41. Page references in the present paper refer to the reproduction.

Bunge M. 1977. Ontology I: The furniture of the World. Reidel: Dordrecht.

Bunge M. 1979. Ontology II: A World of Systems. Reidel: Dordrecht.

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Bunge M. 2014. Big questions come in bundles, hence they should be tackled systemically. Systema 2(2): 4– 13.

Checkland P. 1999. Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. 2nd edition. Wiley: New York NY.

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Craver C, Darden L. 2013. In Search of Mechanisms: Discoveries Across the Life Sciences. University of Chicago Press: Chicago IL.

Drack M, Schwarz G. 2010. Recent developments in general system theory. Systems Research and Behavioral Science 27(6): 601– 610.

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Dubrovsky V. 2004. Toward system principles: general system theory and the alternative approach. Systems Research and Behavioral Science 21(2): 109– 122.

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Ellis B. 2002. The Philosophy of Nature : A Guide to the New Essentialism. Acumen: Chesham.

Flood RL, Robinson SA. 1989. Whatever happened to general systems theory? In Systems Prospects, RL Flood, MC Jackson, P Keys (eds.). Plenum: New York NY; 61– 66.

C Francois (ed.). 2004. International Encyclopedia of Systems and Cybernetics. Saur Verlag: Munich.

Francois C. 2007. Who knows what general systems theory is? Retrieved 31 January 2014, from http://isss.org/projects/who_knows_what_general_systems_theory_is

Friendshuh L, Troncale LR. 2012. Identifying fundamental systems processes for a general theory of systems. Proceedings of the 56th Annual Conference, International Society for the Systems Sciences (ISSS), July 15-20, San Jose State Univ., 23 pp.

Gambrel PA, Cianci R. 2003. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: does it apply in a collectivist culture. Journal of Applied Management and Entrepreneurship 8(2): 143– 161.

Glennan S. 2010. Mechanisms. In The Oxford Handbook of Causation, HS Beebee, C Hitchcock, P Menzies (eds.). Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Goebel BL, Brown DR. 1981. Age differences in motivation related to Maslow’s need hierarchy. Developmental Psychology 17(6): 809– 815.

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Hammond D. 2003. Science of Synthesis: Exploring the Social Implications of General Systems Theory. University Press of Colorado: Boulder Colorado.

Hammond D. 2005. Philosophical and ethical foundations of systems thinking. tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique. Open Access Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society 3(2): 20– 27.

Hofkirchner W. 2005. Ludwig von Bertalanffy, forerunner of evolutionary systems theory. In The New Role of Systems Sciences For a Knowledge-based Society, Proceedings of the First World Congress of the International Federation for Systems Research, Kobe, Japan, CD-ROM (ISBN 4-903092-02-X) (Vol. 6).

Hofkirchner W, Rousseau D. 2015. Foreword. In General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications ( New Edition), L Bertalanffy. Braziller: New York, N.Y.; xi– xix.

Hofkirchner W, Schafranek M. 2011. General System Theory. In Philosophy of Complex Systems ( 1st edn), CA Hooker (ed.). Elsevier BV: Amsterdam; 177– 194.

Hofstede G. 1984. The cultural relativity of the quality of life concept. Academy of Management Review 9(3): 389– 398.

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Hooker CA. 2011. Introduction to philosophy of complex systems A. In Philosophy of Complex Systems ( 1st edn), CA Hooker (ed.). Elsevier BV: Amsterdam; 3– 90.

Illari PM, Russo F, Williamson J. 2011. Causality in the Sciences. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

INCOSE. 2014. A world in motion – systems engineering vision 2025. Retrieved from http://www.incose.org/AboutSE/sevision

E Laszlo (ed.). 1972a. The Relevance of General Systems Theory. Braziller: New York.

Laszlo E. 1972b. Introduction to Systems Philosophy: Toward a New Paradigm of Contemporary Thought. Gordon & Breach: New York N.Y.

Laszlo E. 1974. A Strategy for the Future. Braziller: New York.

Maslow AH. 1954. Motivation and Personality. Harper: New York N.Y.

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Midgley G. 2000. Systemic Intervention: Philosophy, Methodology, and Practice. Kluwer: New York N.Y.

Midgley G. 2003. Systems thinking: an introduction and overview. In Systems Thinking (Volume I), G Midgley (ed.). Sage: London; xvii– liii.

Midgley G, Richardson K. 2007. Systems thinking for community involvement in policy analysis. Emergence: Complexity and Organization 9: 167– 183.

Mingers J. 2014. Systems Thinking, Critical Realism and Philosophy: A Confluence of Ideas. Routledge: New York.

Pinzón L, Midgley G. 2000. Developing a systemic model for the evaluation of conflicts. Systems Research and Behavioral Science 17(6): 493– 512.

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Pouvreau D. 2014. On the history of Ludwig von Bertalanffy’s ‘general systemology’, and on its relationship to cybernetics—Part II: contexts and developments of the systemological hermeneutics instigated by von Bertalanffy. International Journal of General Systems 43(2): 172– 245.

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Psillos S. 1999. Scientific Realism: How Science Tracks Truth. Routledge: London.

Rapoport A. 1953. Operational Philosophy: Integrating Knowledge and Action. International Society for General Semantics: San Francisco, CA.

Rapoport A. 1973. Review of Laszló: the systems view of the world. General Systems XVIII: 189– 190.

Rapoport A. 1974. Review of Laszló E: the system approach to world order. General Systems XIX: 247– 250.

Rapoport A. 1976. General systems theory: a bridge between two cultures. Third annual Ludwig von Bertalanffy memorial lecture. Behavioral Science 21(4): 228– 239.

CAS PubMed Web of Science® Google Scholar

Reynolds M, Holwell S. 2010. Systems Approaches to Managing Change: A Practical Guide. Springer: London.

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Rousseau D, Wilby JM. 2014. Moving from disciplinarity to transdisciplinarity in the service of thrivable systems. Systems Research and Behavioral Science 31(5): 666– 677.

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Rousseau D, Wilby JM, Billingham J, Blachfellner S. 2015. In search of general systems transdisciplinarity. Presented at the International Workshop of the Systems Science Working Group (SysSciWG) of the International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE), in Torrance, Los Angeles, 24– 27 Jan 2015. Available at: https://sites.google.com/site/syssciwg/projects/o-systems-philosophy

Soper B, Milford GE, Rosenthal GT. 1995. Belief when evidence does not support theory. Psychology and Marketing 12(5): 415– 422.

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Tang TLP, Ibrahim AHS, West WB. 2002. Effects of war-related stress on the satisfaction of human needs: the United States and the Middle East. International Journal of Management Theory and Practices 3(1): 35– 53.

Troncale LR. 1978. Linkage Propositions between fifty principal systems concepts. In Applied General Systems Research, G Klir (ed.). Plenum Press: New York, NY; 29– 52.

Troncale LR. 1984. What would a general systems theory look like if I bumped into it? General Systems Bulletin 14(3): 7– 10.

Troncale LR. 2009. Revisited: the future of general systems research: update on obstacles, potentials, case studies. Systems Research and Behavioral Science 26(5): 553– 561.

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Tutor FD. 1986. The relationship between perceived need deficiencies and factors influencing teacher participation in the Tennessee career ladder. Doctoral dissertation, Memphis State University, Memphis, TN.

Von Bertalanffy L. 1955. An essay on the relativity of categories. Philosophy of Science 22(4): 243– 263.

Von Bertalanffy L. 1956. General system theory. General Systems 1, 1– 10. Article reprinted in Midgley, G. (Ed) (2003) Systems Thinking Vol 1, pp 36–51 (London: Sage). Page number references in the text refer to the reprint.

Von Bertalanffy L. 1964. The world of science and the world of value. Teachers College Record 65(6): 496– 507.

Von Bertalanffy L. 1967. Robots, Men and Minds. Braziller: New York.

Von Bertalanffy L. 1969. General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications. Braziller: New York, NY.

Von Bertalanffy L. 1972. The history and status of general systems theory. Academy of Management Journal 15(4): 407– 426.

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Wahba MA, Bridwell LG. 1976. Maslow reconsidered: a review of research on the need hierarchy theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 15(2): 212– 240.

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Weaver W. 1948. Science and complexity. American Scientist 36: 536– 544.

Wilby JM, Rousseau D, Midgley G, Drack M, Billingham J, Zimmermann R. 2015. Philosophical foundations for the modern systems movement. In Systems Thinking: New Directions in Theory, Practice and Application, Proceedings of the 17th Conversation of the International Federation for Systems Research, St. Magdalena, Linz, Austria, 27 April – 2 May 2014, M Edson, G Metcalf, G Chroust, N Nguyen, S Blachfellner (eds.). SEA-Publications, Johannes Kepler University: Linz, Austria; 32– 42.

Ashby WR. 1956. Introduction to Cybernetics. Wiley: Chichester.

Ashby WR. 1960. Design for a Brain: The Origins of Adaptive Behavior. Chapman and Hall: London.

Bateson G. 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology. University of Chicago Press: Chicago.

von Bertalanffy L. 1951. General System Theory: A New Approach to the Unity of Science. Human Biology 23: 4, 30.

Caws P. 1963. Science, Computers, and the Complexity of Nature. Philosophy of Science 30: 158– 164.

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Caws P. 1965. The Philosophy of Science: A Systematic Account. Van Nostrand: Princeton.

Caws P. 1989. Structuralism: The Art of the Intelligible. Humanities Press: Atlantic Highlands, NJ.

Caws P. 1993. Yorick’s World: Science and the Knowing Subject. University of California Press: Berkeley and Los Angeles.

Caws P. 2000. Structuralism: A Philosophy for the Human Sciences, 2nd edn. Humanity Books: Amherst, NY.

E Laszlo. (ed.). 1972. The Relevance of General Systems Theory: Papers Presented to Ludwig von Bertalanffy on his Seventieth Birthday. George Braziller: New York.

Messadié G. 1961. Une extraordinaire société scientifique. Science et Vie, 27 August, 27.

Popper K. 1972. Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach. Clarendon Press: Oxford, 10.

Wells O. 1970. How Could You be so Naïve? Modern Books: Beaconsfield.

Blitz, D. (1992). Emergent evolution: Qualitative novelty and the levels of reality. Dordrecht: D. Reidel.Google Scholar

Bunge, M. (1974–1989). Treatise on basic philosophy. (Eight Volumes) Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Company.

Bunge, M. (1981). Scientific materialism. Dordrecht: D. Reidel.Book Google Scholar

Bunge, M. (1992). System boundary. International Journal of General Systems, 20(3), 215–219.Article Google Scholar

Bunge, M. (2001). Philosophy in crisis. Amherst: Prometheus Books.Google Scholar

Marquis, J.-P. (1996). A critical note on Bunge’s system boundary and a new proposal. International Journal of General Systems, 24(3), 245–255.Article Google Scholar

Abdel-Malik, A. The project on socio-cultural alternatives in a changing world: Report on the formative state (May 1978-December 1979). United Nations University, Tokyo, 1980.

Althusser, L. For Marx. New York: Random House, 1969.

Bahm, A. J. Philosophy: An introduction. New York: Wiley, 1953.

Bahm, A. J. Organicism: The philosophy of interdependence. International Philosophical Quarterly,1967, 7, 251– 284

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Bahm, A. J. Polarity, dialectic, and organicity. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C Thomas, 1970.

Bahm, A. J. Metaphsics: An introduction. New York: Harper and Row, 1974.

Bahm, A. J. The philosopher’s world model. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1979. (a)

Bahm, A. J. Review of J. G. Miller’s Living Systems. General Systems Bulletin, 1979, 10, 31– 32 (b)

Bahm, A. J. Five types of systems philosophy. International Journal of General Systems, 1981, 6, 233– 237

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Bahm, A. J. The wholes and parts of things, unpublished.

Battista, J. R. The holistic paradigm and general systems theory. General Systems, 1977, 22, 65– 71

Web of Science® Google Scholar

von Bertalanffy, L.. General systems theory. New York: Brasiller, 1968.

Boodin, J. E. Three interpretations of the universe. New York: Macmillan, 1934.

Boodin, J. E. The social mind. New York: Macmillan, 1939.

Bowler, T. D. General systems thinking: Its scope and applicability. New York: Elsevier North Holland,1981.

Buckley, W. Sociology and modern systems theory. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1967.

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Bunge, M. A systems concept of society: Beyond individualism and holism. Theory and Decision,1979, 10, 13– 30

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Busch, J. A. Cybernetics III. A systems-type applicable to human beings. Cybernetica, 1978, 22, 89– 103

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Busch, J. A. Re-thinking social organization: Sociocy-bernetic approaches to the morphogenic nature of groups, forthcoming.

Cooley, C. H., Angell, C. R. & Carr, L. J. Introductory sociology. New York: Scribners, 1933.

Katz, D. & Kahn, R. L. The social psychology of organizations. ( 2nd Ed.). New York: Wiley, 1978.

Koestler, A. The ghost in the machine. London: Hutchinson, 1967.

A. Koestler & J. A. Smythies (Eds.). Beyond reduc-tionism. London: Hutchinson, 1969.

Koestler, A. Janus: A summing up. London: Hutchinson, 1978.

Kovalchenko, I. & Sivachev, N. Structuralism and structural-qualitative methods in modern historical science. Social Sciences, 1978, 10, 60– 82

Kurzweil, E. The age of structuralism: Levi-Strauss to Focault. New York: Columbia University Press,1980.

Laszlo, E. Introduction to systems philosophy. New York: Gordon and Breach, 1972.

Levi-Strauss, C. Cultural anthropology. Garden City: Doubleday, 1967.

Maruyama, M. The second cybernetics: Deviation-amplifying mutual causal processes. American Scientist, 1963, 51, 164.

Web of Science® Google Scholar

Miller, J. G. Living systems. New York: McGraw Hill, 1978.

Mussolini, B. The doctrine of fascism. Firenze: Val-leachhi Publisher, 1938.

Piaget, J. Structuralism. New York: Basic Books, 1970.

Taschidian, E. The third cybernetics. Cybernetica, 1979, 19, 91– 104

Wiener, N. Cybernetics. New York: Wiley, 1948.